Nervation Theatre, New York

October 30th, 2025

Reviewed By: Varsha Radhakrishnan for Line & Verse

Photo credit: Shail Joshi

The joy of veneration, a personal love of the practice of classical dance, and endearing camaraderie seemed to represent the foundations of 3, presented by Swati Seshadri, Dhruva Lakshminarayanan, and Meghana Boojala. The small-scale gathering, the balance of respectful informality in setting, performance, and costume, and the close proximity between artist and viewer, rendered an experience similar to that of a Mehfil.

Swati, Dhruva, and Meghana presented a repertoire that was grounded in an anthology of popular devotional pieces, with a handful of non-devotional works.

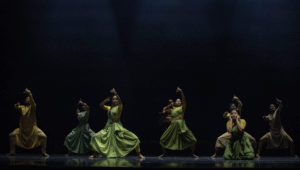

Beginning with a short instrumental rendition of Bhagyadaa Lakshmi Baramma set a tone of celebration and light-heartedness. The dancers (as devotees) prepared for prayer and procession with playful humanity. When Devi emerges, she subtly adds her magic to the preparations with a mischievous benevolence. All three dancers utilized space well, carouseling through formations and vignettes. The joyful nature of this piece, and the absence of a preamble allowed the piece to breathe freely — to be experienced rather than explained.

Following this was the popular invocatory piece in honor of Ganesha – Ananda Nardana Ganapatim, performed by Swati. The bliss and abundance associated with Ganesha came through in Swati’s energetic and amply-projected movements, while her firm footwork offered a groundedness to the piece, including in the chittaswaram. Though Swati moved with rigor and grace, the more narrative-based abhinayam in this piece felt overfilled with hand gestures.

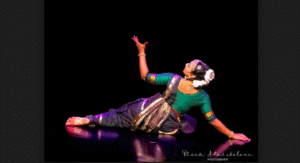

Meghana’s solo, drawn from the texts of Sri Krishna Karunamritham, explored devotion as yearning and discovery. The musical score for this piece offered a powerful sonic landscape for the choreography, which alternated between the longing to witness Krishna, and a reminiscence of his winsome traits. The strength of Meghana’s performance was her stayibhava of devotion that persisted throughout the piece, along with the limber ease with which she moved. At moments in the piece, the vigor and flow in Meghana’s movements dropped, occasionally bringing down the energy of the piece. Further, when portraying Krishna, her performance could have invited greater mischief, a lighter irreverence to balance the devotion.

Maadumeikkum Kanne, performed by Dhruva as Krishna and Swati as Yashoda, was a conversational duet in every sense — sung, gestured, and felt. The bantered exchange between concerned mother and persistent son allowed the dancers to react live to one another, evoking an empathy in the audience for their humorous intimacy. While the delivery was intentionally informal, it felt underplayed from a vocal and dance performance lens. A live orchestra or more stylized delivery might have preserved its whimsical nature while elevating impact.

Dhruva’s Brochevarevarura followed — a portrayal of surrender and faith. His abhinaya conveyed humility and vulnerability of a devotee that is expressing his plight at having no one to protect him, but Rama. A jathi punctuated the piece and renewed the rhythm and energy of Dhruva’s performance. With fuller engagement of the spine and arms, Dhruva could have further projected his abhinaya.

Next came Yaro Ivar Yaro, performed by Swati and seen through Rama’s eyes. The song’s lyrics chronicle the first moment of romantic interest between Rama and Sita, humanizing the venerated. Adaptations exist that tell the story from both characters’ perspectives. In beholding Sita, Swati embodied a Rama who is smitten. Her use of aangika abhinaya captured Rama’s essence – his composure, curiosity, flickers of awe and restlessness all at once.

The penultimate performance was a Tirupugazh, celebrating Muruga’s six faces, and pairing Meghana’s dancing with Dhruva’s narration. The part sutradhar, part duet format was conceptually interesting, but theatrically uneven, splitting focus between voice and movement, making it challenging to enjoy the combined artistry. Additionally, there were moments of nritta in the piece that would have been more effective with percussion. Overall, this choice to bring to life a central work in medieval Tamil Literature was thought-provoking and has great future potential for exploration.

The finale, Adiya Padathai, choreographed and performed by Swati and Meghana, began with Swati’s unaccompanied alapana, which morphed seamlessly into recorded rhythm — a finessed start. Their interplay alternated between rhythmic chant and cholukkatu, between dancer and dancer, performer and viewer, adding complexity to the piece. In the more dynamic movements, there were opportunities for greater coordination in timing. The work’s stated intention was to blur the lines between performer and spectator, by engaging the audience in collective prayer of Om Namah Shivaya. A recommendation for this is to probe deeper into what it means to turn spectators into participants, and to take bolder risks in the process. Overall, this piece made for a strong culmination to the program.

3 was, above all, an enjoyable, intimate experience that journeyed into popular works, with each artist bringing their unique strengths. What would take this showcase to the next level is a more unified artistic voice that also invites the audience to probe deeper. In their introductions, Swati, Dhruva, and Meghana discussed their personal ethos in dance; those perspectives could manifest more discernibly in their future works and shape a steadfast vision. Doing so could allow for a collaboration that not only honors tradition, but expands upon it.