Tramway, Glasgow

22nd November, 2025

By: Durga Chatterjee

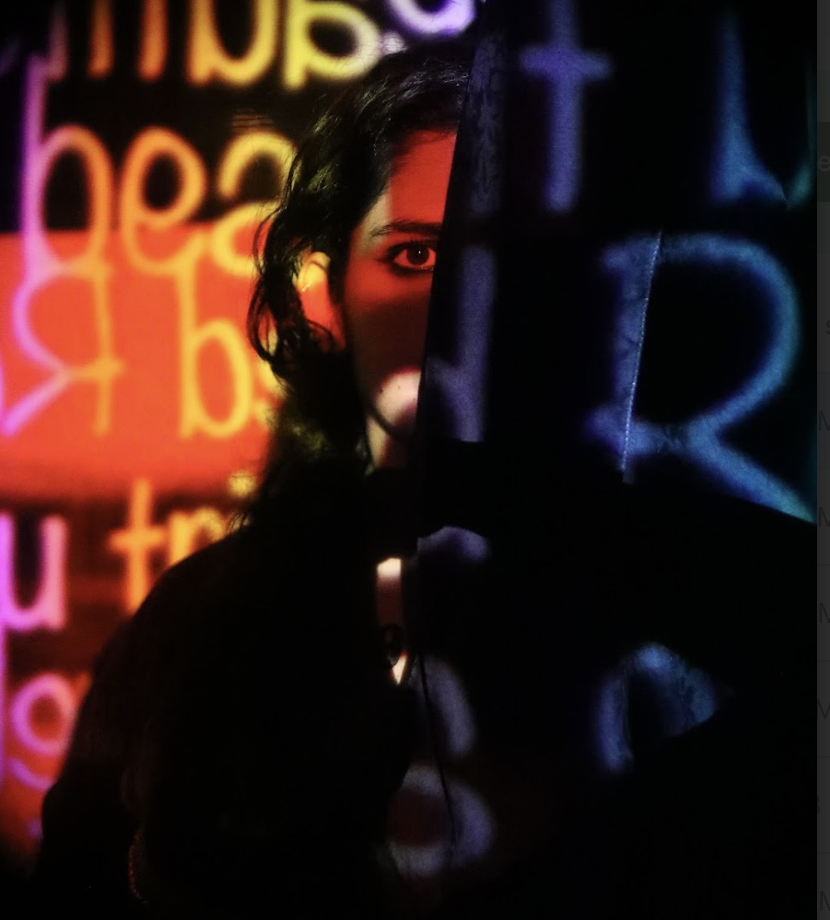

Image credit: Susan Hey

Himadri Madan’s Gaze is a brilliant multi-media experience that tells the story of a woman as just that; a story of a woman. Whether you relate to her, disagree, whether you feel for her or feel afraid of her, that is up to you as the audience.

Walking into the space felt strangely intimate, as though I was entering someone’s home rather than an exhibition. I’d seen Himadri once before in Edinburgh as part of a collaborative film installation, where she was one of the dancers. At the time, I was a nervous first-year student who hesitated before asking her a question during the panel, but her warm response made art, and the people who make it, feel accessible. That memory came flooding back as I entered the space with a friend, ready to encounter her work again in an entirely new form.

Seeing the set up from my seat, the title Gaze became clear: I was gazing, looking through a translucent fabric that parted the audience from the installation. It hinted at a different world, like looking into someone’s room, someone’s life, through a curtain that you aren’t supposed to draw. At that moment, the experience began.

The experience was split into two parts; in the first half we could walk through, and interact with the installation. We were invited to move through it, following a path that had certain instructions guiding us – that we pick up and move objects, or write down words we carry within ourselves. As I walked in, the first thing I noticed were the ghungroos, relatively small objects carrying generations of dancers and stories within them – laid on the floor. Then a dressing table appeared, cluttered with intimate objects. Large screens in the corners began playing a video that showed hands trying to fit items into the compartments of a jewellery organiser. The visuals instantly felt familiar: the daily rituals that women perform, also speaking to the attempt to arrange, contain and categorise pieces of ourselves.

Further inside, traditional jewellery hung from draped fabric. Suddenly, I was transported to Kolkata, to my grandmother’s room, to that distinct but vague scent of compact powder and watching her getting ready to go out. The next dresser was stacked with books and make-up. These sensory fragments – sight, smell, sound, memory were all woven seamlessly into the installation, making the work feel personal and shared all at once.

A recurring motif was the translucent cloth, through which we saw Himadri in the second video. Slightly blurred, partially obscured – like the way women are often seen through a softened, distorted social lens, smiling and silent. In the video we are introduced to the tune of folk song Mai He Kolonkini Radha, which resurfaces in the performance. At the end of this film she revealed her arm, marked with the words woman / ladki. A quiet yet forceful declaration of identity, the kind that resists erasure.

The following two films shifted in tone. Words marked her skin as she walked through the street; later she frantically attempted to wipe them away in the privacy of an indoor space. The act captured something painfully universal: how labels seep into the body, even when we try to shed them.

When we returned to our seats, the performance began. Artist and musician Ankna Arockiam entered first and sat, followed by Himadri herself. The scene mimicked an ordinary kathak rehearsal – warm, informal, deceptively simple. Before beginning to dance, she commented that something felt strange, then peered through the cloth at us: “I feel like someone is watching”. The audience chuckled, aware of the irony. We were watching her, but now the work began to watch us back.

She explained they would rehearse thaat and abhinaya. As Ankna counted – ek, do, teen, chaar, I found myself wondering what those syllables meant to those around me. To me, they were loaded with rhythm, training and years of embodied memory, but maybe to others they were just sounds.

Her abhinaya piece called back to the sweet melody of Mai He Kolonkini Radha, which Ankna sang with grace. For a moment, we were in Vrindavan; Radha, her companions, Krishna under a tree playing the flute. But then she stopped mid narrative and questioned it. “Why can’t a story about a woman just be about the woman?” This marked a highlight for me, it was a sharp opening into the politics of storytelling – why are women’s tales so often structured around men?

The narration reminded me of my own bharatanatyam rehearsals, how when we were taught a narrative sequence, our teacher would make us recite what was happening in the sequence and we physically danced it out. A method that now resurfaced in my body as nostalgia, while I watched intently to see if I understood every word of her bodily storytelling.

Himadri then began telling us a story her nani used to tell her about the three Draupadis. One who lived in a palace. One who lived in a smaller house, but among a loving community. And one who lived alone in a hut, called Dopdi as a mockery. The parable blended this character from the Mahabharata with the tale of the Big Bad Wolf in a way that felt playful yet devastating. The wolf tried to reach the first two Draupadis – one fortified and the other supported, but the third, entirely alone, confronted him with nothing but herself.

Through gesture, footwork and expression, Himadri embodied all three Draupadis. It was the most compelling moment of the evening when she finally stepped through the veil and made direct eye contact with us, something tightened in my stomach. I still can’t tell whether I felt drawn to or afraid of her – but perhaps that uncertainty is the point. Are we, as the viewers, on her side? Or are we them, the villagers?

After the performance, I asked her why she returned to kathak, despite training in multiple forms. Her answer reassured me: kathak feels natural to her body; choosing bharatanatyam would mean creating more for the form than for herself. As someone navigating similar questions about movement in my practice, I felt seen. Another reason she gave was the inspiration of mehfil from Mughal courts, and how kathak stays true to those inspirations.

What struck me most about The Gaze was how effortlessly it wove together myth, memory and social commentary. During the question and answer session one of the artists recalled a New York Times article claiming feminism was “ruining the workplace” – a reminder of how relevant the topic remains and how urgently we need stories like these.

Over an hour passed without my noticing. Outside of Tramway, my friend and I unpacked everything we had seen. I found myself explaining thaat, abhinaya, and the echoes of my own training embodied in work. In that conversation I realised how profound the piece had felt. I deeply admire artists like Himadri, it is because of women like her that young artists like myself feel more confident in ourselves. From having similar unruly curly hair to having a longstanding interest in dance and movement, I feel connected to her work.

The Gaze is evocative and transcendent, rooted in the loneliness and fullness that coexist within womanhood. It reminds us that even in the smallest gestures and stories, we carry entire worlds. I sat in the bus curious and full of questions. Where does a woman’s story go when she chooses herself? What happens when the gaze she returns is steadier and stronger than the one cast upon her? What does it mean to inherit myths, and what does it mean to rewrite them? What would Himadri create next if she let kathak lead her somewhere entirely unfamiliar?

And perhaps the most lingering question – when we leave the performance, whose gaze do we carry with us: hers, or our own reflected back?

Himadri Madan is a performer, choreographer, and dance teacher trained in Bharatanatyam, Kathak, and Bollywood. She holds a BA (Hons) in Choreography from Bangalore University and an MFA from Trinity Laban in London. Her work explores socially and politically engaged themes through Indian classical dance, with recent projects including The Ticking Clock, Maiden | Mother | Whore, and the ongoing development of The Gaze.

Ankna Arockiam is a Glasgow-based vocalist, lecturer, and researcher originally from Hyderabad, trained in both Indian and Western classical music. She holds a PhD on cultural identity in young Western classical musicians and teaches at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. Alongside an active performance career, she is the founder of Glasgow Sitare and a leader in multiple arts organisations, recently appointed Artistic Director of Westbourne Music.

Durga Chatterjee learnt bharatanatyam from the age of four in Mumbai from Shrimati Kamat. She is currently a student of fine art at the Glasgow School of Art. She enjoys creating installations from natural material, painting, watching dance and participating in community-led projects.