Through London Adavu and London Margazhi, the ex-management consultant turned full-time performing artist builds spaces where tradition meets bold reinvention. Guided by what she calls her “triangular compass” Ami embodies an audacious tenacity: when something does not exist, she does not wait for it – she builds it.

By Deepa Ramathilagam

“Potential, purpose, and impact, that is the triangular compass that has always guided me,” says Ami Jayakrishnan, her words sharp yet serene, as we settle into a corner of Foyles Café on Charing Cross Road. “Every time I take on something new, I ask myself: does it serve all three?”

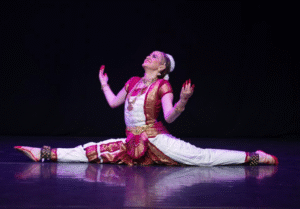

Across the table, Ami seems calm, even contemplative, but a spark hides behind her composure – a quiet boldness that reveals as soon as she starts speaking about her work. Her oxidised jhumka catches the late-autumn sun and her hands trace subtle arcs in the air, unconsciously embodying the dance form she has dedicated herself to.

“When I moved to London, there wasn’t a bharatanatyam community in central London,” she recalls. “There were pockets of activity, but no meeting ground. I thought, if it doesn’t exist, I’ll build it.”

That impulse to create rather than wait led her to found London Adavu in 2019. Inspired by NYC Adavu in New York, Ami started modestly, and within months a handful of dancers had become a growing community.

Then the pandemic hit.

“I had just left my full-time job to build a portfolio career as a dancer and freelance consultant,” Ami says with a wry smile. “And then, the lockdown. I still remember leaving things at my desk thinking I’d be back in a few days!” When studio meet-ups fell silent, she pivoted. “People were craving connection. I moved Adavu online, a way to remember movement, discipline, and belonging”.

That audacity to pivot, create, and lead defines Ami’s ethos. Six years on, London Adavu has grown into one of the UK’s largest bharatanatyam communities – a pulsating network of dancers, choreographers, and learners who gather to practice and grow.

Ami, however, is not alone. “I have an incredible team of volunteers,” she says. “We are here because we care deeply about what this community has become and can do.” In six years, Adavu has offered more than 220 regular meet-ups, 25 workshops, 15 Masterclasses, two Summer Schools and two Showcases with over 150 dancers participating.

“It was never meant to be just another class,” she says firmly. “I wanted it to be a focal point of creativity, collaboration and community. A space where dancers could experiment boldly, fail safely, and discover new possibilities.”

I wanted it to be a crucible for creativity.

That vision birthed Adavu’s flagship programmes:

-The Summer School, with intensive masterclasses in technique and performance practice from acclaimed UK and international artists;

-Ensemble, a performance wing for UK-based dancers to create and perform together;

-The Showcase, a platform for emerging creators to present works-in-progress to an intimate, interactive audience.

Through these initiatives, London Adavu has become a vibrant ecosystem for Indian classical dance: not just for practice, but for growth, collaboration, and visibility. “We’ve hosted brilliant artists from India, Singapore, Australia and the UK,” Ami notes. “The goal is to connect global artists with UK-based practitioners, making London an essential node in the international classical-arts network”.

Still, she acknowledges the challenges. “Yes, the global classical dance industry is broken,” she says. “Many artists have normalised working for free. That willingness undercuts the entire ecosystem. When everyone performs for free, no one gets paid.”

From its inception, Adavu has challenged that norm. “We made a deliberate choice to pay all our artists and facilitators well above industry standards,” she insists. “Being community-led allows flexibility. Adavu proves a collective model can be financially sustainable, artistically rigorous, and ethically fair, and we’re piloting a new social enterprise model for the arts.”

“When everyone performs for free, no one gets paid.”

Her background gives her a unique lens for this structural thinking. Before moving fully into the arts, Ami spent nearly ten years managing strategy and operations projects in high-impact environments. “I’ve always been obsessed with systems and problems, how things work and how they can work better,” she says. “So when I entered the arts, I couldn’t help but ask: what alternative models could make this sustainable?”

That question underpins her latest project, London Margazhi 2026, a two-day festival reimagining the traditional Indian Margazhi season for a London stage. For those unfamiliar, Margazhi, which originated in Chennai, is the iconic season of dance and music, now adopted in many Indian cities. During this season, these cities transform into living theatres. To imagine something similar in London is, frankly, audacious and might seem improbable – which makes it quintessentially Ami.

“I have danced through three consecutive Margazhi seasons in India,” she says. “It’s beautiful and hugely rewarding, but financially unsustainable for many abroad. So I thought, why not bring the Margazhi spirit here?”

“a collective model can be financially sustainable“

The Festival will feature eight dancers over two evenings, each performing extended solo recitals with live musicians. What makes it radical, is not its format but its ethics. “One of the things I care about most is fairness,” Ami adds, her tone softening. “Indian classical dance is essentially a solo art form. Festivals usually expect dancers to cover performance costs, musicians, rehearsals, everything. At London Margazhi, the festival absorbs those costs so dancers can focus on their performance”. She smiles, then adds, “Fairness shouldn’t be revolutionary, but in our field, it still is.”

London Margazhi also aims to broaden the audience. Alongside performances, the festival will hold engagement activities and open rehearsals to introduce Bharatanatyam to wider cultural circles beyond the South Asian arts sector. “We want to reframe bharatanatyam as contemporary, alive and accessible,” she says. That sense of purpose runs deep in her thinking. “I want dancers to see the arts as a career path, not a side passion. We’re building scaffolding for that: paid opportunities, mentorship, community infrastructure. If this works, it could transform how classical arts are sustained in the UK.”

As daylight fades and the chatter around us swells, Ami’s ‘triangular compass’ – potential, purpose, and impact, feels less a personal philosophy and more a manifesto. Her audacity doesn’t roar, it resonates in the rhythm of someone who refuses to wait for doors to open and instead builds the stage herself.