Sohini Alam in conversation

Simone Sultana spoke to Sohini ahead of Khiyo's performance at the Southbank Centre's South Asian Sounds Festival:

Khiyo: From Bangladesh to Britain | Sun 10 March | 3 pm | Purcell Room at Queen Elizabeth Hall

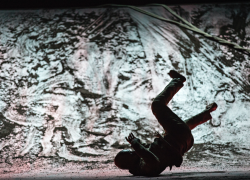

Khiyo’s deeply soulful tunes – mixed in with tracks that make the spirit fly – must reflect some of the breadth of experience that has informed your songwriting. I know your world changed irrevocably aged nine, and the trajectory that you followed has brought you here, performing with your own band Khiyo, belting out Bangla-fusion songs with Lokkhi Terra, on stage with the likes of Akram Khan, co-developing the soundtrack for the powerful documentary Rising Silence – all the while raising a young daughter and caring simultaneously for your own father who has dementia. Can you give a potted history of what has brought you here and if you are conscious of how the musician in you has been affected by your journey?

Anyone’s art is bound to be affected by their life experiences, and I am no different. The difficult times in life have not only made me better able to appreciate the good times, they have made me a better artist. How can anyone accurately express pain with it having felt it? The shock of losing my mother at nine was compounded by moving from London to Dhaka within days of losing her. The language I spoke, food, friends, weather, family - everything changed. Only the music remained, so perhaps I nurtured it without fully realising why.

You sing in Bangla – is this significant and does it shape your song-writing? Intrigued also to know your thoughts on how a non-Bengali speaking audience hears your words and feels the song compared to your Bengali fan base.

I couldn’t accurately describe how non-Bengalis find my music and respond to it. I can say that the feedback I’ve received is that the universality of music as a language means that people can let themselves feel the emotion of our music even when they don’t understand the words. We do provide translations of Khiyo tracks on our website as we know our audience is international. The experience of having a varied cultural heritage is one that more and more people have. Even non-Bengalis can relate to the very human themes of love, loss, longing, and protest. The reason I sing in Bangla is because while my first language of speech was English, my first language of music was Bangla. I was surrounded and taught to sing by a family of musicians steeped in Nazrul and Rabindra Sangeet. So I grew up in London speaking English, but when I want to express myself musically, I find my voice is naturally inclined towards Bangla.

How does a young girl growing up in London have Bangla as her go-to language of song?

My grandfather, aunts, uncles and my mother either played an instrument or sang. Traditional instruments from the sitar to the santur were part of my furniture. London in the 1980s had a vibrant Bangla arts and culture scene and my mother gave singing classes at the Bangladesh Bhavan where I too was a young student. In fact, I used to complain about having to go to these classes until I was unceremoniously sent off to dance class – and realised my mistake. The teaching was rigorous and I will never forget the talented taskmasters I endured. But it set the foundations for my life in music.

Tell me about the genesis of the band Khiyo and the creative process between you and your fellow band members Oliver Weeks and Ben Heartland.

Olly contacted me back in 2007 after having seen me perform to deputise for the celebrated Bengali singer-songwriter Moushumi Bhowmik with whom he and Ben were in a band. Moushumi Di had just moved to Kolkata, and Olly wanted to keep exploring Bengali music, so he and I jammed together one day. Our arrangement of 'Nishi Raat' came together so easily that we were fooled into thinking we would be able to make music with very little effort. It was beautifully naive. We would cook big batches of food and then eat, chat, and play, so it wasn’t long before Ben joined in.

Khiyo has had a broad world music following since its inception but its first official single – a take on the Bangla anthem – catapulted you into a Bangla audience but also threw you into a tornado of ‘political' controversy. How if at all this has affected your cautiousness or approach to songwriting? Extending this question to the music you have written for the difficult and potentially controversial subject matter of the documentary Rising Silence, what role do you feel music & song plays in advocating for social/political issues?

The connection between music and politics is something that exists everywhere. For Bengalis, however, the two have been intimately intertwined throughout history. 1952 (The Bengali Language Movement) and 1971 (the Bangladesh Liberation War and creation of Bangladesh) are the most obvious examples. My being taught that history through music meant that my own music was never going to be candyfloss-like. Olly and I both tend to gravitate towards serious, miserable songs. We have to make an effort to keep it from getting too heavy sometimes. I’m not sure either of us have musical cautiousness. If we did have it, we’d stop blowing our music budgets on obtaining orchestral sounds. 'Amar Shonar Bangla' was our first recorded release. The controversy surrounding it didn’t change our approach to music in the slightest. It made us realise the power that controversy can wield, but it didn’t make us feel like we had to fan those flames for publicity because we simply aren’t those people. In my work with Khiyo and my arts company Komola Collective, I get to collaborate with amazing artists to make music on difficult social and political issues. The themes we work with are controversial enough!

Simone Sultana wears several hats, at times together. She is an economist, photographer, works in governance and oversight for social impact organisations (from development, climate to human rights), occasionally works behind the camera in film and even more occasionally enjoys interviewing artists.