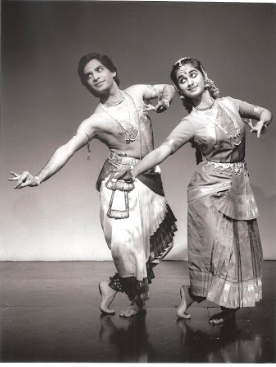

Nina Rajarani

Jahnavi Harrison talked to dancer, teacher and award-winning choreographer Nina Rajarani as she prepared to present her new duet with Y. Yadavan to mark Srishti's Silver Jubilee in 2016. We are sharing this article from Pulse Issue 133 as Rajarani releases 'Srishti Squared', a digital work involving ten dancers and musicians, created entirely during lockdown.

‘Nina (didi) is a headstrong, determined performer and teacher who knows what she wants and is unabashed in stating her truth plainly and obviously. What I admire about this is that one always knows where one stands with her. As a dancer she’s extremely musical and has supreme command over rhythms. She is staunch in her adherence to what she sees as the stylistic integrity of bharatanatyam and she shares this knowledge unreservedly.’ (Sooraj Subramaniam).

I’d be sitting on the tube, on my way to university in Russell Square. Just before Baron’s Court station I’d think 'Should I just bunk today?' I’d be thinking and thinking and then the train doors would open and just before they closed I would jump out and think 'Yay! I’m going to dance all day!'

Nina Rajarani laughs gleefully, a mischievous twinkle in her eyes. We are sitting at Harrow Arts Centre, a place where she has spent most of her adult life, since her dance school, Srishti, was founded here in 1991. Just two days before our interview she celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the school with a Silver Jubilee show that saw both current and ex-students performing as well as her professional company. She has had a packed career over the last three decades, spending as much time on the stage herself as in the classroom, training hundreds of young dancers. I ask her if her guru at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Shri Prakash Yadagudde, knew she was skipping lectures to come and practise.

'I think he did know,' she smiles, 'but he didn’t say anything because if he did he would be a party to the crime! I was his duet partner at the time so we would practise together all day long. It was incredibly fun. I thought that was what it would be like to be a professional dancer – I didn’t realise you had to earn a living as well.'

The stark realities of life were perhaps underlined even more strongly for Rajarani, who experienced culture shock moving from a privileged and sheltered childhood in Nigeria to the UK just before a political coup took over the country. Aged 13, she and her younger sister were promptly signed up for dance classes. 'At first my parents would take us, but after some time they said ‘We can’t be doing this any more’ – so my sister and I would go alone on the train. It wasn’t even safe to walk on the street alone in Nigeria, but now we were doing the shopping, cooking and cleaning while our parents were working very hard, setting up their new business.'

A tough work ethic seems to be something ingrained in Rajarani, who speaks often of ‘horse-blinkered’ determination and focus. While she attended two to three dance classes a week, she aimed for the top academically. 'I was always the ideal student. I never intended to be a dancer; I really wanted to be a psychiatrist.' Everything was going well until she did her arangetram halfway through A-levels. 'I couldn’t see how I was going to continue dance, even as a hobby, if I wanted to do medicine. It came as quite a shock to me.' She still applied and got into medical school, but her determination quickly waned.

Right on cue, she was alerted to an Arts Council grant by Pushkala Gopal, whose name comes up, fairy godmother-like, at so many crucial moments in Rajarani’s story. 'I thought "I can’t just keep bunking lectures", so I applied without saying anything to my parents. When it was approved, I just said "I’m going’". My parents begged me to at least finish a degree as a fall-back option, but I really felt "I just have to do this – it’s the right time for me."'

The next two years were spent in Chennai under the tutelage of the Dhananjayans, where she squeezed every last drop out of the experience. 'It was the most inspiring time of my life. I had classes in dance, music, Tamil and Sanskrit from 8 am to 8 pm every day. At 8 pm I’d come home and be revising and writing up meticulous notes till 12 or 1 am! For a varnam I’d have a whole thick book!'

Returning to the UK was again a shock. Aged 21 with no immediate money-making prospects, her parents urged her to open a dance school. While she began conducting classes in Harrow, she started work in Shobana Jeyasingh’s company. 'She found out I had come freshly-trained from India. We still joke about it when we meet,' she laughs.

'She remembers me as this very blasé, outspoken, audacious person, which I think I still am, but maybe toned down a little! I told her I want to start my own company so I turned down the offer, but she encouraged me to reconsider, advising that it would help me to get on the inside and understand how a company is run. She was right. By the time I finished touring her production I was ready to put in an application for my own work.'

As a dancer, Rajarani has always been a delight to watch – with precise technique and a vividly expressive face, she navigates the repertoire of traditional bharatanatyam with ease and style. Thanks to Arts Council funding year after year, Srishti has earned a well-deserved reputation as one of the UK’s foremost South Asian dance companies. Though her performance work started out as more traditional solos, she has shown flair and much originality as a choreographer for ensemble works. Her pieces have spanned a broad aesthetic, both innovative and accessible – incorporating African dance, Shakespeare, corporate life and even football! She continues to break from the norm by incorporating live musicians into the choreography – something that perhaps worked to greatest effect in her 2006 Place Prize-winning QUICK! Rajarani entered ‘by mistake’ on the insistence of her manager but ended up winning, beating 204 other entrants and twenty competing choreographers. 'It was definitely the greatest moment of my career. I felt like it was the biggest reward for all the risks I’ve taken from the time I was a teenager – it was paid back to me, by being given that recognition.'

Through ups and downs, no one could deny that Rajarani’s career has been a richly varied and successful one. She narrows her eyes when I say this: 'You think so? I don’t know...I think I’ve had a phenomenal number of challenges – I’ve made productions through real hell in my life. I’m not from an artistic background, I’m not even South Indian, I’m Punjabi for God’s sake! I think I’m in this from something due to me from a previous birth or by mistake. People do think I’m successful, but I feel I’m very much self-made, I didn’t have any sugar daddies or inherited wealth, I just worked really hard and I just believed in myself always. In my whole life I’ve just been in my own world, like a horse with blinkers forging ahead and doing what I need to do. I’m poor at publicity and at saying the right things and wooing people – I just feel like, well I’m here, if they want me they’ll ask me – it’s just not me to say ‘Oh, please have me!'

Rajarani’s artistic work has only gone from strength to strength through her collaboration with her husband, vocalist-composer Y. Yadavan. At the time they met, she was in a troubled marriage, raising two young children. 'In 2001 Pushkala had to pull out of singing for our school show and recommended "a really fine Sri Lankan singer, just moved over and living in Harrow." I said ‘If he lives here in Harrow and I haven’t heard about him, he really can’t be talented!’ I was expecting an oily-haired man with a big moustache – typical Sri Lankan guy! He turned up really well-dressed! I gave him a cassette and script to prepare and at rehearsal the next day he just sat silently and watched – it was a massive dance drama – Dashavataram written by Swati Thirunal – possibly the hardest thing I’ve ever been given to learn. The following day he just opened his mouth and sang the whole thing perfectly! I was completely gobsmacked! It was phenomenal.' She grins, 'I wasn’t in love with him at that time, I wasn’t even separated yet from my husband, but I was really in awe of him. I immediately asked him to teach music in my school. I got really excited because I loved his singing.'

Yadavan dropped out of his day job in an accounting firm to compose and perform in her 2002 production SHE, and they have worked together ever since. 'Eventually I fell madly in love with him,' she laughs. Their new duet work together, Sevens, is a piece based on the saptapadi, seven traditional Hindu marriage vows. The piece was developed with an R&D grant that allowed the couple to go to India and be mentored by Chitra Visveswaran and Rajkumar Bharati. She brims with enthusiasm for the piece, which will be performed at Alchemy and the Navadisha conference in Birmingham. She clearly loves performing with her husband, though adds, 'It’s not as rosy as it might look! To a normal musician you’re working with you can say, you sang it too fast – and they’ll say ok, I’ll adjust tomorrow. But your husband will say, "No, you always think I’m singing it faster! I’m singing it the same as yesterday! From now on we’ll record it and we’ll see who’s right!" We have those kind of stupid arguments. Everyone around us is looking and thinking – oh my God, here they go again…'

Her dance school continues to grow, now registered by the ISTD as a dance training and examination centre for prospective teachers of bharatanatyam and kathak, and her youth dance company Srishti YUVA Culture goes from strength to strength, now ably performing some of her touring company works.

In the midst of this marathon of activity Rajarani, now in her mid-forties, is still holding it all together – a woman to be reckoned with. She sighs heavily when I ask about the next decade: 'There is no flashy plan! I have a really hard one-and-a-half years coming up with my two eldest doing their A-levels and GCSEs and am thinking about planning an arangetram for my daughter. Once I’ve passed that I will have some breathing space. I’m in no rush to do anything any more. I’ve already shown that I can do production after production. It has been the biggest challenge to have combined my role as a parent and have this career. If someone wants to be a performer they need to be very self-centred – I haven’t done that – it’s impossible to do that when you’ve been through a bad marriage and had four children all through C-section and need to prioritise their needs, you don’t eat on time or sleep enough – I think my body’s taken a real beating, I don’t actually know how I’m still going. But if you don’t have a family, you lose out on another piece of life. I’ve overdone everything! Everything has been excessive.'

She sits back, a content smile on her face.

'But I wouldn’t have it any other way. I really wouldn’t.'