Mandelbrot, Meera’s Madhava, and Messy Meaning-Making

An alliterative title, three seemingly divergent concepts, and the idea that repetition can produce complexity.

Durga Tilak takes us into her imagination, visualising mathematical principles living out in performance arts.

Each occurrence of the word Mandelbrot carries a different hyperlink; please do check these out.

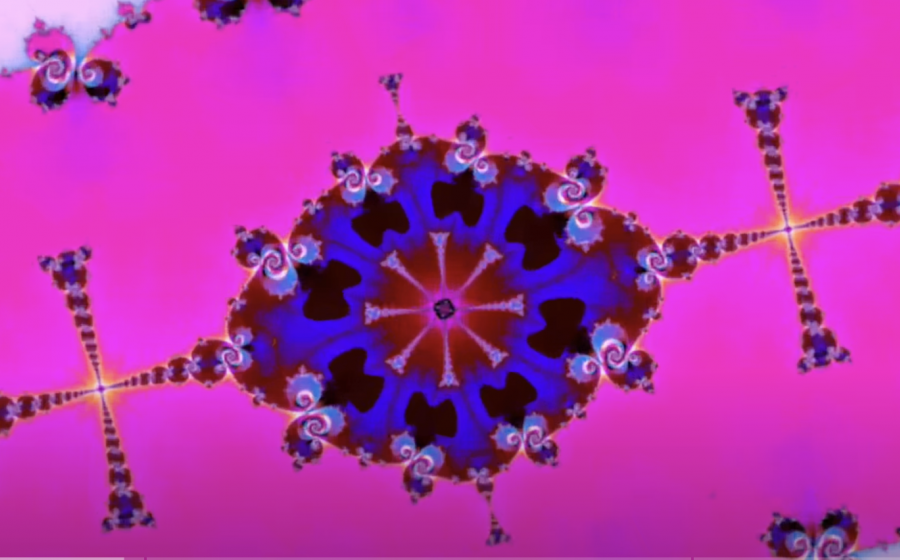

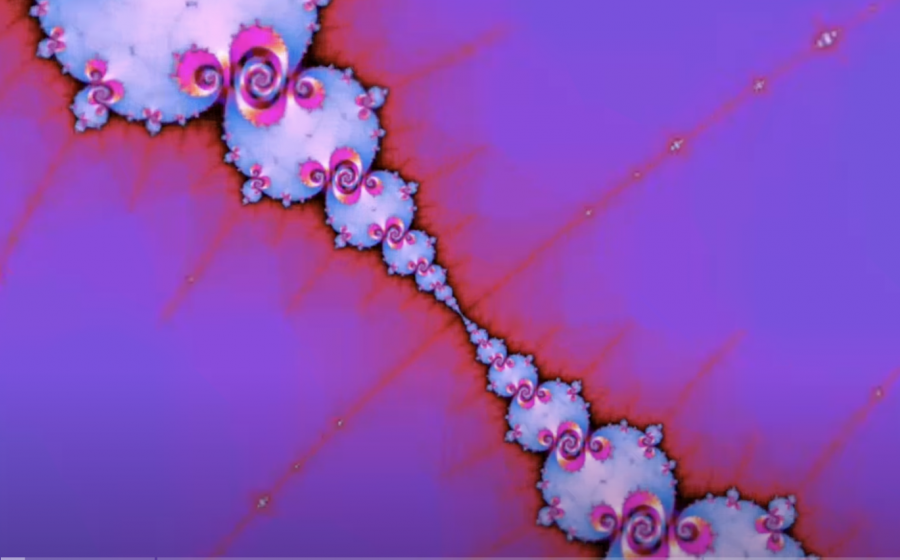

A few days ago, I was sent a YouTube short of Neil Degrasse Tyson and Grant Sanderson speaking about the Mandelbrot set. The Mandelbrot set is an intricate, ever-evolving geometric pattern in the two-dimensional plane of complex numbers. Summarily, this is how it goes: One starts at zero, computes its square, and adds a complex number ‘c’ to it. The same operation is carried out with the resulting number, and this process is repeated multiple times. In certain cases, this computation goes on indefinitely, while in others, the outcome of this repetition is restricted to a well-defined space on the 2D complex number plane.

While the maths behind it is highly nuanced (and certainly eye-widening), I was gripped by one thing that Sanderson said: ‘A repetition of a simple rule produces a mind-bogglingly intricate shape. This shows that complexity does not have to emerge from complex rules. It is possible for complexity to emerge from simple rules.’

The more I thought about it, the more I realised that artists have proven this time and again through their practice. In mathematics, sharp objectivity produces intricacy when a relatively simple procedure of repetition is applied to it. On the flip side, in the arts, the complexity is hidden in the folds of interpretation and perspective, waiting for repetition to come and unmask it.

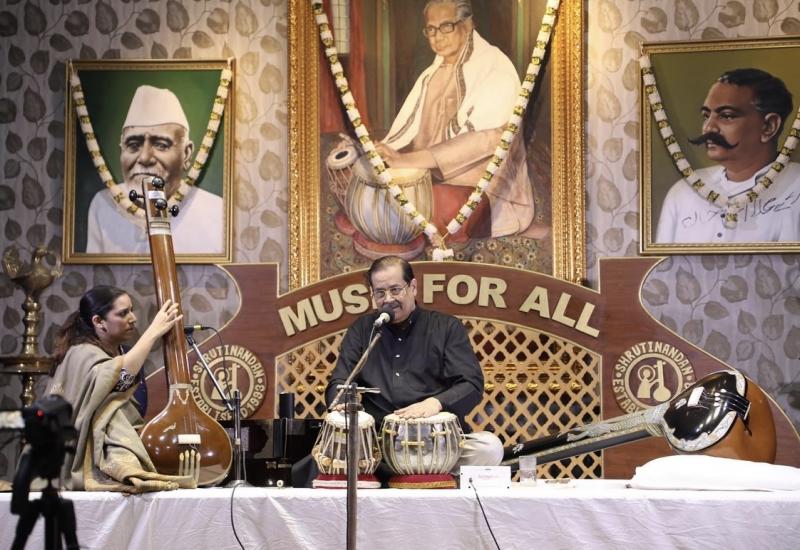

Charukeshi and Meera Sreenarayanan: A Touching Dialogue

Not so long ago, the world was grappling with the horrors that the pandemic had unleashed upon us. Amidst the uncertainty and hardship though, some changes to the status quo, born out of the need to adapt to the emerging times, brought some cheer to the pervasive bleakness. Amongst these was the Music Academy’s decision to broadcast some of the December season’s performances on its YouTube handle. That was when I first witnessed the magic of Meera Sreenarayanan’s rendition of Innum En Manam, the evergreen Varnam* [Charukeshi, Aadi, Lalgudi G Jayaraman].

In the Varnam, the conventional practice has been to iterate each line of the lyric multiple times in the performance. The intention is to create musical space to explore the many facets of the lyrical meaning. While there are guidelines that inform how many times a particular line may be repeated, by and large, these are not set in stone.

The Charukeshi Varnam that Meera performed has made a home in my heart and my memory for several reasons. The most important of these is that it transcends the physicality and the bodily accuracy that a composition like the Varnam demands. In her rendition of the Lalgudi Jayaraman masterpiece, the physical precision of Meera’s nritta interjections is almost incidental – such is her command over her craft. But what she does to unveil complexity using simple rules is astounding. Through the systematic repetition of the lines of the composition, she paints the detailed story of not one, but two nayikas, each afflicted by Lord Krishna’s absence.

The first perspective is painted from the point of view of a young maiden who is irrevocably in love with the dark-hued Lord, while the other is drenched in unyielding devotion for Him. How does Meera birth complexity? Using the simple tool of repetition, the constant she adds each time to the iterative process changes: In one instance, the nayika expresses her love for Krishna and pleads him to return to Vrindavan. Then she requests, questions, demands, and cajoles. The words do not change. The lyric cycles as her portrayal subtly shifts around the central theme of separation. And with a little hitch of breath, a slight shoulder shrug, a lifted brow, a nod of the head, she unearths newer meaning to those very same words. Compellingly, the complexity of the rendition takes on new heights when, in the blink of an eye, Meera transforms from a lovesick maiden to a heartbroken devotee. Once again, the lyric remains the same. But the same words now capture a different region of the emotional spectrum. Now, we witness the plight of a devotee who has to endure the absence of their protector, the person they understood as the physical embodiment of divinity.

In both the interpretations, Meera’s loyalty to the character she embodies in that wisp of time is heart-wrenching. In one moment, one can connect with the pangs of separation that the lovelorn nayika feels for the man she is in love with. In the next, it is impossible to get bleary-eyed while witnessing the torture the devotee suffers on being robbed of the company of their god. Like the ever-flowering Mandelbrot set, Meera’s Charukeshi blooms into deeper, nuanced emotions each time I watch it. Like the Mandelbrot set, her Varnam too, succeeds in drawing patterns within a carefully defined boundary of meaning-making. Each constant she adds sits at the heart of a unique universe of patterns that revolves around it.

Interpretation and the Joys of Meaning-Making

‘Messy meaning-making’ was the WhatsApp status of one of my sisters-in-law way back, when statuses were those little by-lines just under one’s name on the app, and not the flashy 24-hour phenoms that they are currently. What stayed with me (apart from its delightful alliterative appeal, of course) was how pithily it captured the human condition today. One never understands oneself completely, let alone another entire human being. So to take on a conversation is to willingly sign up to embrace the countless perils of meaning-making.

However, thanks to this undefined nature, meaning-making, along with its perils, also ushers in associated joys. I like to think of this variable nature of interpretation as a parallel of the limiting or bounding condition of the Mandelbrot set. For certain values of the constant, the set is unstable. One sees no discernible pattern; it appears like a random, out-of-control scribble. But within a well-understood region, this same tweak-and-repeat process produces enchanting results. What defines pretty and what defines pointless? In math, the boundary conditions play gate-keepers. In art, interpretation does.

The more I thought, read, and watched, interpretation (as far as the Varnam was concerned) seemed to occur on one of two levels: at the level of the theme, and at the level of the word.

Theme-centric interpretation is the route of meaning-making we discussed vis-à-vis Meera’s rendition of Charukeshi, where the unchanging lyric was interpreted through two alternating hues of the overarching theme of separation and (re)connection. What emerged was a painting flecked with myriad shades of love, separation, attachment, and devotion.

The other route of meaning-making, which I have not seen frequently in action, is the interpretation and expansion of an idea that is rooted in a single word of the lyric. Only two examples that I have witnessed (so far) spring to my mind:

1. Sumasayaka [Karnataka Kapi, Roopakam/Tishra Ekam, Swathi Tirunal] a rendition by Christopher Guruswamy.

2. Samiyei Azhaittodiva [Navaragamalika, Aadi, K N Dandayudhapani Pillai] by Dr Janaki Rangarajan.

In his choreography of Sumasayaka, Christopher Guruswamy zooms in on the word Sumasayaka (which, in Indian mythology, is one of the several names for Cupid, the god of love) in the first line of the composition. The Varnam itself speaks of the heroine’s distress stemming from her separation from Lord Padmanabha. What makes Guruswamy’s interpretation so beautiful is how he ropes in a related sub-plot that adds layers to the main storyline (watch the excerpt and listen to him speak about it here).

The other example of Dr Janaki Rangarajan’s choreography of the celebrated Navaragamalika Varnam is unfortunately something I cannot offer visual reference for (I remember watching her perform this piece at her recital at the University of Pune a long time ago). What Dr Rangarajan does is similar to what Guruswamy did in Sumasayaka: she takes a small but picturesque detour in the fourth line of the composition by describing the wedding of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati. The line (bhUmi pugazhum dEva manOhari magizhum) speaks of the greatness of Lord Shiva, the consort of Goddess Parvati.

In both these cases, the complexity is born from the repeated use of not the theme or an entire line, but rather, by immersing (however briefly) into a single word that offered ample scope to augment the central idea. While the performative narrative departs from the main idea for a while, the departure is not a divergent one – it does not cause dissonance.

Even with the scope of nritta or pure dance in bharatanatyam, one sees the principle of the repetition producing distinct patterns. While this offers the potential of a longer meditation on the physical form of the dance style, let us (for now) restrict ourselves to the scope of the Varnam. Here, the first jathi (usually) follows the traditional trikaal pattern. One rhythmic phrase is repeated progressively in proportions of one (vilambit), two (madhya), three (tishra), and four (druta). The phrase remains constant till the teermanam (the jathi’s threefold closing pattern) is reached. However, as the cadence of the phrase increases in steps of one to four, the associated movement also undergoes a natural change which reflects the altered distribution of the rhythm. The underlying principle remains the same, albeit not-so-obviously. However, it seems derivative given the dynamic nature of the rhythm sections in the Varnam. This coupled with the intricate mathematical permutations and combinations within the rhythm tends to eclipse the simplicity of the repeat-and-tweak principle.

Doing the Same Thing, Expecting Different Results

Einstein supposedly said: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” Although he said this in the context of the going-ons of the world, we have proof that quantum mechanics can repeat processes and yet, produce different results each time (this brilliant article here speaks of it at length).

A simple idea, its repetition, and the consequent birth of complexity – happening in both the sciences and performing arts. Are the sciences and the arts more similar than we think? Or are we all equally, uniformly, simply, gloriously insane?

For comments and feedback, please write to tilak.durga96@gmail.com

*You ask even a fledgling Bharatanatyam student what the most difficult composition in the Margam is, and they will say it’s the Varnam. Known as the pièce de résistance of the Bharatanatyam repertoire, this composition is a long, continuous piece that narrates the state of mind of the protagonist. The protagonist, in the widely practised collection of Varnams, is the Nayika (the woman in love). However, Varnams with a male protagonist (the Nayaka or the man in love) are not unheard of. Also popular are Varnams that are written in the voice of a devotee, in which case, the gender identity is secondary to the emotions of devotion, worship, and service. Most often, the entire composition is narrated solely from the perspective of one of these three protagonist possibles.