Dastaan - with Sarvar Sabri

Sonia Sabri Company

mac Birmingham

21 March 2018

Sonia Sabri Company’s Dastaan (meaning story) brings together multiple art forms across multiple cultures. Six wonderful musicians take us on a journey from Rajasthan, through Iran to Wales. A foot-tapping song about a camel beauty contest (yes, apparently such things exist), with Pulkit Sharma working rhythmic miracles on a set of khartaal, is succeeded by a lyrical Persian melody and then a wistful thumri in the liquid voice of Sanchita Pal. Sam Frankie Fox concludes the first half with a harp tribute to Welsh settlers in Patagonia (who knew?!) developing into a haunting Welsh lullaby.

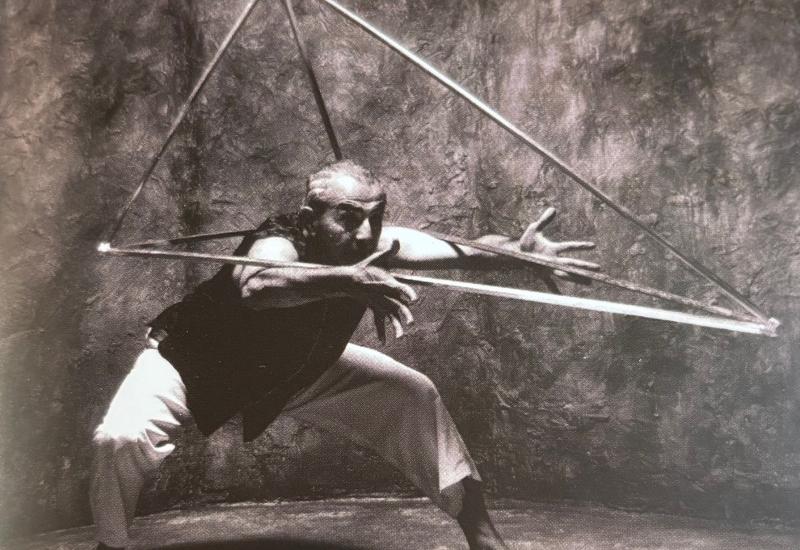

The second half gravitates around a film by Matthew Beckett, featuring former BRB ballet dancer Marion Tait. Choreographed by Sonia Sabri, Tait’s movement intertwines with Nasta’liq (Persian calligraphy) drawn by the multi–talented Mehdi Jamali (who also performs as vocalist and instrumentalist). The silent film is held within the space by the musicians who deftly interweave their respective musical traditions in an acoustic tapestry so seamless that it seems inevitable, and that yet succeeds in cherishing the distinctive and unique features of each form. Constant and necessary as gravity, long term collaborators Alvin Davis on saxophone and Sarvar Sabri on his customary range of percussion, cradle the performance, allowing the piece to venture into uncharted musical waters, and yet not lose its way. As a metaphor for an intercultural society the performance is in itself uplifting, modelling a way of being in which no tradition is compromised or diminished, and yet each appears more compelling, more poignant, for being part of the whole.

As across cultural traditions, so across art forms – the film meshes perfectly with the soundscape that informs it. On the screen, dance and calligraphy play with each other. Tait echoes the sweep and stillness of the written patterns, while these curves and pauses of the writing in turn form part of the dance. The film is a poem that, in more ways than one, invites us to reconsider our relationship to time. Tait is an older dancer – and the film embraces and celebrates this, focusing on her beautifully lined face and her life worn hands, and holding these in the context of the falling leaves, the growing and fading day, the furrowed bark of an age old tree. Like the best poetry, the film summons us to stop – to be attentive – to take time. Slowly, carefully, lovingly, Tait whittles the wood to make the pen for the Nasta’liq, and slowly, carefully, lovingly, Jamali forms the words that are both art and prayer. Where does our busyness take us? In what way does our clinging to youth, our pursuit of speed, of action inform us? In the lilting cycles of the music, in the deliberate carefulness of the calligraphy, in the gentle turning and reaching of Tait’s movement, Dastaan reminds us that for all we might like to believe it, our time is not our own. Our time, to echo the title of the Persian song performed by Jamali, exists In Conversation with the Ultimate (whatever this ultimate may be). In its fearless and unapologetic acceptance of ageing; in its committed patience and appreciation of the taking of time, Dastaan provides a welcome corrective to the relentless round-the – clockness of twenty-first century life, and reminds us that our Dastaan – our story, as every story – takes its own time – and this is at it should be.