Secular Themes in Bharatanatyam: Ideas for an Inclusive Future Part II

In the first essay of this series, I presented my synthesis of the relevance of religion in bharatanatyam in relation to the present day multicultural, multi-ethnic, and multifaith audience, and current and potential practitioners. I also presented to the dancer the argument for inclusivity along with some examples from the mostly secular ancient Tamil sangam literature. In this second part, written in consultation with Ms. Vaidehi Herbert, an expert in sangam literature and a teacher par excellence, I will explain more about sangam literature, and some of its influences on later religious works that are enthusiastically adapted into the bharatanatyam repertoire, while the secular root of this beautiful imagery (i.e. sangam poetry) remains largely unexplored and ignored by the dance community.

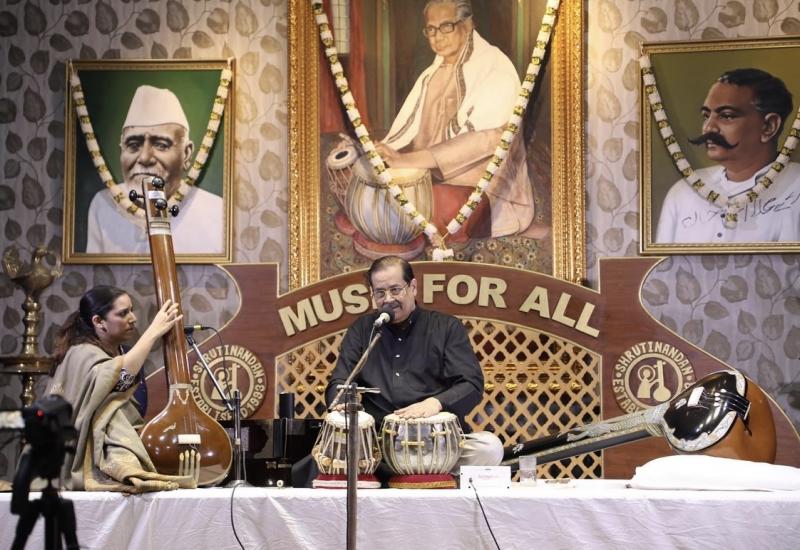

Photo Credit: Prasad Golkonda

The Sangam period in Tamil literature contains a plethora of mostly secular poetry masterpieces that follow a highly conventionalised system. These poems range from descriptions of landscapes or thinais, the season and time of the day associated with it, the flora and fauna supported by the land, the people who live there and their occupations, and most importantly, a hero, a heroine, and sometimes their friend, mother, foster mother, mistress, enemy, or child and their relationships. The poems could be about love (akam thinai) or warfare (puram thinai); they could describe a friend advising the hero or the heroine, or a foster mother in search of her daughter who has recently eloped with her beloved, or a mistress teasing the hero about how subservient he is with his wife.

They could be in the form of a poet advising a king not to kill the young sons of his enemy whom he vanquished in the war, or a poetess ‘marvelling’ at the shiny, new, and unused weapons of a king who is inexperienced in warfare while comparing him with the enemy king who is so experienced in the ways of war that his weapons are rusty and often being repaired at the smith’s. In fact, sangam poetry is more liberal than most expect it to be. There are poems that talk about premarital love and poems that describe a ‘chaste’ person as one who has good qualities rather than the word being associated with a female’s virginity (karpu = ‘chaste’, root word kal meaning ‘to be educated’). Other poems describe how both young men and women in this society had the freedom to choose their spouses, and poems that describe men and women even drinking alcohol together.

Photo Credit: Prasad Golkonda

Sangam poetry has influenced poets and writers across time including three poets from the Hindu religious revival period called the bhakti period circa 800 CE: Thirumangai Alvar, Nammalvar, and Andal. The concept of madal eruthal (literally means climbing the leaves) features in sangam poetry where the hero threatens the heroine that if she would not disclose their love in public, he would ride a fake horse made out of palm leaves (panai madal). The children in the village would pull the “horse” so the entire village would know of their love (e.g. kurunthokai [the second anthology of Sangam literature] – poems 173, 182, kalitthokai [the sixth anthology of Sangam literature] – poem 58).

This imagery is expressed in the religious collection of 4000 verses on Lord Vishnu, the Divya prabhandam collection by Thirumangai Alvar (poems 2710, 2790) and Nammalvar (poems 3371, 3372). Thirumangai Alvar and Nammalvar imagine themselves as women who are in love with Lord Vishnu and threaten to perform madal eruthal if he fails to express his love for the poet. Another theme originally found in sangam poetry but adapted to suit a religious storyline is the concept of bangles falling from the wrists of the heroine because of the pasalai disease (roughly translated to ‘love sickness’) that makes the heroine’s hands very slender. This is commonly seen in kurinji thinai (mountainous landscape) of sangam literature. Andal uses this same concept beautifully and says how her kazhal vaLai (the bangles on her arms) have become kazhal vaLai (falling bangles) because of Vishnu, with her typical word play on the two meanings of the word kazhal (‘arm, to remove’).

Ironically, we frequently witness bharatanatyam performances of the religious Divya Prabhandam poems (for instance) but almost never see any presentations of the original secular sangam poems. Is it not sad and unnecessary that these beautiful concepts and imagery need to be woven into religious contexts to make their way into bharatanatyam when the secular root provides us with so many more possibilities of expressing love towards fellow human beings? Why do we force ourselves into conveying these feelings only towards a Hindu god or goddess rather than towards each other?

I believe that these poems that describe earthly landscapes, that are rich in linguistic traditions, and that evoke beautiful human emotions deserve an equal if not a better place in the bharatanatyam repertoire than their religious counterparts which, ironically, ‘hijack’ the original poems for their themes. Exclusively performing bharatanatyam that is steeped in religious themes rather than their richer, more textured original poems risks our art form remaining something of an obscure and inaccessible mystic medium from the East. I want to challenge the reader to consider reverting back to the beautiful and secular roots of the sangam poems for their next inspiration, which may enrich their experience of bharatanatyam and may help to expand its accessibility to other, non-Hindu humans.

Postscript: I direct the motivated reader to Ms. Vaidehi Herbert’s website on this topic and which explains sangam conventions and scenarios in great detail and translates many of the sangam poems to English. She also draws parallels between the sangam poems and some of the Divya Prabhandam poems in this website,

About the author: Dr. Prathiba Natesan Batley is founder/chairperson of the non-profit organisation Eyakkam Dance Company. She is also senior lecturer in the Department of Life Sciences at Brunel University London.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Ms. Vaidehi Herbert and Dr. Nicholas John Batley for their help.