Paradise Lost : Hebridean Treasure

Paradise lost

Hebridean Treasure Lost and Found

Netherbow Theatre, Edinburgh,

1st March 2019

Reviewed by Caroline Higgitt and Roger Robertson

‘The traveller from India to Scotland can here see, on the cold, sterile rocks of Harris, the petrified symbols of a faith left living behind him on the hot, fertile plains of Hindustan.’

This passage comes from the introduction to Vol. 1 of Carmina Gadelica, Gaelic songs and incantations collected by Alexander Carmichael in the late nineteenth century. It may have been the inspiration for this charming and thought-provoking hour-long performance devised by John Philip Newell and directed and choreographed by Shane Shambhu with musical direction by Mischa Macpherson.

The work reimagines the Celtic spirituality of a remote past with the aid of Gaelic prayers collected (and possibly ‘improved’) by Carmichael; a time when people lived at one with God immanent in Nature. It traced the suppression of this spirituality by a succession of historical events including the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, and the disaster of the Highland Clearances with their accompanying atrocities in the 19th. (The suppression of Gaelic culture described first hand by Carmichael’s informants occurred, of course, in the 19th century, presumably more the result of the Disruption in the Church of Scotland and the wider Evangelical Movement than the 16th-century Reformation).

Newell, as Carmichael, together with Alison Newell and Iain Louden, recited passages drawn almost entirely from Carmina Gadelica’s preface. This was accompanied by the wonderful singing of Ankna Arockiam and Mischa Macpherson (who also played the clarsach) with excellent tabla player Hardeep Deerhe (perhaps rather under-used on this occasion), and the beautiful fiddle playing of Charlie Stewart (BBC Radio Scotland Young Traditional Musician in 2017) ably supported by Cameron Newell, with Alistair Iain Paterson (of the bands Barluath and Skipinnish) on the harmonium.

The singers and instrumentalists offered Gaelic and Indian-inspired music, playing sometimes together, sometimes separately and often to accompany the dancer. Particularly beautiful were the moments when the two singers sang together, each in their own language, combining in an effective fusion that was neither entirely Indian nor Gaelic.

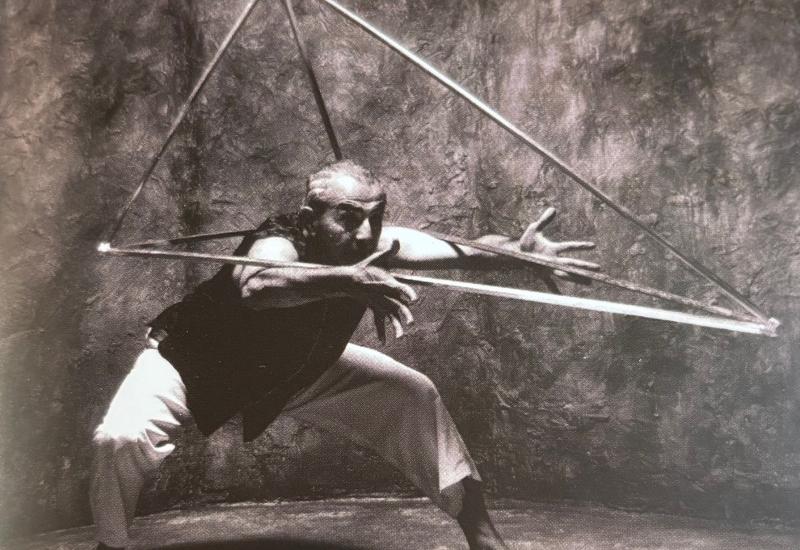

On stage throughout was dancer Kirsten Newell. Trained in Indian classical and modern dance, she initially used the gestures of the classical style to convey images of a people living in harmony with nature and the elements. As the narrative progressed, her dancing, while still retaining a classical idiom, became more overtly a form of mime illustrating the narrative. With increasing activity on stage, the restricted performing area of the Netherbow became visibly problematic.

Publicity for Hebridean Treasure promised ‘what has never been attempted before, a memory of the forgotten influence of India on the Celtic soul’. This bold claim would need to be backed up by considerably more evidence to be convincing. Celtic spirituality, as presented here, has parallels in many different world cultures; there seems no reason to claim a special link with India. There are, on the other hand, interesting parallels between the prayers recorded in Carmina Gadelica and St Francis’s famous Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon.

John Philip Newell (poet, writer, minister in the Church of Scotland and one-time warden of the Iona Community) is a prominent teacher in the field of Celtic spirituality. Four family members have cooperated in this production to offer an optimistic note for a future where a renewed respect for nature will form part of the rebirth of this lost spirituality.