Embracing Bharatanatyam - Navigating Tradition, Belonging and Identity

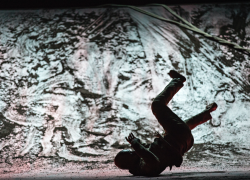

Arangetram photos: by Simon Richardson

When I walked into my first ever bharatanatyam class in Cambridge almost 11 years ago, I remember feeling curious and excited about nurturing my interest in the Indian arts. I didn’t have this opportunity in my native Italy, but after moving to the UK, I couldn’t continue my gymnastics career, so I started dancing instead. I learnt about Indian Classical dance forms during my first trip to Tamil Nadu in 2012. At the time, however, I did not fully grasp the complex history and tensions around these art forms.

As I continued learning adavus, jathis and margams over the years, I also kept being asked questions like how I got into bharatanatyam, why I do it and how I can relate to it considering I do not have Indian or South Asian heritage. While most of these were understandable questions, I started noticing that this curiosity often turned into suspicion or criticism, almost as if my involvement in this art form crossed a forbidden boundary. This conundrum is not unique to Indian arts: a few years ago, for example, some members of the public were outraged by a non-white actor playing the mermaid protagonist in the movie adaptation of a Danish fairytale. It seems that, for some, the aesthetic of performers is more important than the story and what it can teach us.

I still keep being asked questions about my motivations and my intentions behind performing bharatanatyam. It makes me wonder why this curiosity is continues to be so prevalent a decade later, even after numerous non-Indian artists have made their mark in Indian Classical dance forms over the years, such as Sophia Salingaros, Lucrezia Maniscotti, Sarah Gasser, and Magdalen Gorringe in bharatanatyam and Ileana Citaristi, Elena Catalano and Katie Ryan in odissi. I find it perplexing that dancers trained in Western dance forms do not seem to be questioned as rigorously on their motivations, regardless of their background. It’s as if ballet, or other Western dance styles, were the only available, or acceptable, dance forms around the world.

Despite my ever-supportive teacher and mentor, Krishna Zivraj-Nair, this incessant questioning and perception by others often made me question myself, my dedication to the art form and whether I belonged in the bharatanatyam classroom, on stage and, later, my legitimacy as a teacher. It even stopped me from applying to and participating in South Asian dance programmes and beyond.

Bharatanatyam, like all other art forms, has a distinct aesthetic deeply entwined with the history and geography in which it flourished. Evolving over centuries, this aesthetic has undergone significant transformation and has been largely influenced by upper castes in India since the 20th century. So, what happens when dancers defy this traditional mould? In other words, to whom does bharatanatyam belong, if indeed an art form can be owned?

These are important questions for me as a white bharatanatyam dancer engaging in these conversations and practices. To answer them, it is necessary to understand the concepts of culture and cultural appropriation. The ideas of culture and heritage are, often, erroneously considered static. In reality, culture and heritage are dynamic and inextricably linked to the time, place and people in question. As such, while bharatanatyam can trace its origins back to Sadir, an art form performed centuries ago, the aesthetic, the practice and the communities have indeed changed, not least given the sanskritisation of the art form from the 1940s/1950s onwards, and the widespread presence of South Asian diaspora communities globally. The history and the narrative of bharatanatyam are often told in binaries, but there are many grey areas which should be acknowledged, including and especially caste struggles in the arts. But this is a story for another day.

My experience as a non-Indian bharatanatyam dancer is that others often try to tell whether the art form I have been learning for almost 11 years is part of my identity or not. Bharatanatyam is a part of me and, to me, it is also part of my culture. I kept asking myself over and over again whether there is some sort of legitimacy in this belief, so much so that I decided to complete a research project about culture and Indian classical dance at the University of Cambridge.

During my research, I learnt about the sociological term ‘cultural capital’, coined in the 1980s, which refers to an individual’s social assets they use in their lifetime, such as their education. The scholar who coined it, Pierre Bourdieu, further divided cultural capital in embodied cultural capital, which is what we accumulate through our lived experiences, objectified cultural capital, which is gained through the study and appreciation of tangible assets, and institutionalised cultural capital, which is cultural capital recognised by institutions, such as a degree from a university. Learning about the theory behind cultural capital made me realise that culture can be learnt in a number of different ways – and bharatanatyam has been part of my lived experiences for over 10 years. Therefore, as long as an art form’s history and legacy is understood, acknowledged and respected, anyone can learn bharatanatyam. And every artist owns their practice.

The idea of angashuddhi (body purity) is important in Indian classical dance forms – over the years, it has come to refer to correct technique, but in previous decades it has been weaponised by some to indicate who is ‘pure’ enough to perform the art. In early 2023, Leela Venkataraman’s review of devadasi performances was heavily criticised as she suggested that the performers' technique needed improvement. This led me to wonder: considering devadasis have been the keepers of the art form for centuries, can their technique be wrong? And if Venkataraman were a devadasi herself, would that comment have been acceptable/accepted? And, further, how can I – as a white bharatanatyam dancer – honour and respect their legacy?

This discussion is not about appropriating bharatanatyam: it is the very opposite. This is about de-centring the hegemony of dance forms from the current Western epicentre. After all, when we mention ‘contemporary’ dance, we don’t mean contemporary bharatanatyam, kathak or odissi (whatever that might look like). Rather, ‘contemporary dance’ refers to a dance style that blends elements from other dance forms, all Western. While bharatanatyam is recognised as a transnational art form, this is mostly due to the global reach of the South Asian (and, more specifically Indian) diaspora, rather than because all dance forms across geographies are given equal consideration.

The bharatanatyam aesthetic has now departed from the traditional margam format, especially when performed on digital platforms. We now see bharatanatyam being performed to Indian cinema music and we see artists who are proficient in multiple dance styles, producing incredible fusion pieces, departing from the concept of bharatanatyam as religious only. There are now bharatanatyam compositions about Jesus and Christian stories. Historically, many musicians and singers in royal courts were Muslim, yet were singing in praise of Lord Krishna. The history of bharatanatyam is incredibly diverse, with the dedication to the art form being the most important characteristic of an artist.

While for some bharatanatyam is part of their religious practice and their cultural identity, this is not the only way that bharatanatyam can be lived. I choose to take the stories from Hindu mythology – on which bharatanatyam choreographies and Carnatic music usually draw – as stories from which I can learn. Stories that can be told and heard regardless of faith and culture. One of my favourite abhinaya pieces is, for example, the bhajan Thumak Chalat Ramachandra by Saint Tulsidas. The characters in the story are a young Lord Ram and Queen Kaushalya from Hindu mythology, but the story is simply of a mother watching her child learn how to walk.

The beauty of dance is that it can become very personal both for the dancer and for the audience alike – and because we are all different, there is space for everyone’s interpretations and there is also space for different representations.

An artist's sincerity, intention and dedication to their practice, and their genuine understanding and respect for an art form's legacy should outweigh markers like nationality, gender or religion. Dance embodies joy and movement, transcending cultural confines. Bharatanatyam will always be an Indic art form, and anyone wishing to learn it should appreciate its roots, histories and terminologies: yet, alongside innovation, it is time to open the door for true diversity and inclusivity in bharatanatyam and Indian classical dance forms, and not just as a tick-box exercise for funding or social media. As for me, I have left unnecessary questioning behind and I look forward to deepening my bharatanatyam practice even further and doing my best to speak up for and champion inclusivity whenever, wherever and however I can.