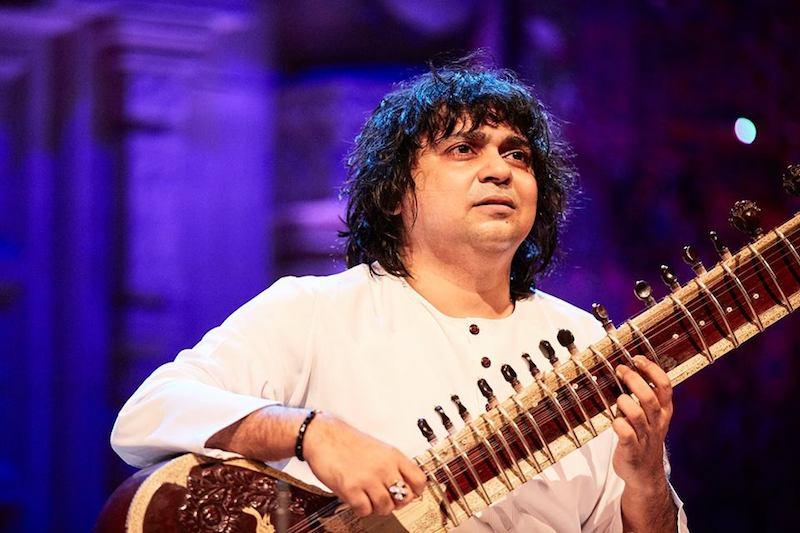

Niladri Kumar: Seduced by the Sitar

Niladri Kumar: Seduced by the Sitar, 13 March 2018, Milton Court Concert Hall, London – Reviewed by Ken Hunt

The 600-seater Milton Court Concert Hall is tucked behind London’s Barbican and is one of the Barbican and Guildhall School of Music & Drama’s complex of venues/stages. This concert formed part of the Darbar Festival, announced its artistic director Sandeep Virdee. Niladri Kumar, word has it, is a sitar player to really watch out for. Actually, in his range of performance and interpretative skills, he demonstrated a rare eloquence and sense of dynamics and proved himself to have an extra special extra something.

Accompanying him for the first time was the master percussionist Sukhvinder Singh. As Sukhvinder Singh Namdhari (but already known as ‘Pinky’), he was thrust into the world music consciousness in 1993 through Ry Cooder and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt’s A Meeting by The River, a Grammy winner in the World Music Album category. For the first half of the Milton Court recital, Pinky stuck to jori (or jōri). By no less a personage than the tabla laureate Zakir Hussain, Singh has been declared the master of the jori. A double drum resembling a scaled up tabla in appearance, it’s not to be confused with the jōrhi or pāwā jōrhī – alternatives for alghoza, the double woodwind folk instrument of north-western India and Pakistan. For the second set he stuck to the more conventional tabla.

Photo: Kirit Singh and Jasdeep Singh

Seduced by the Sitar is a banner title that Darbar has used before and should consider pensioning off. An example might be Mita Nag’s 2015 Seduced by the Sitar… performance (Pulse, Winter 2015, p. 23). It conjures the ghastly era when India was all spirituality, sex and sitary mysticism. Niladri quipped he would have a hard time explaining the concert’s title to his father. (That his dad is the sitarist Kartick Kumar went unmentioned.) One neat little coincidence connects Niladri Kumar and Mita Nag. Each plays a sitar from the same Calcutta-based instrument maker. The late Hiren Roy made sitars for Senia gharana (school of playing) notables including Nikhil Banerjee, Annapurna Devi and Ravi Shankar. Niladri’s father, studied with Ravi Shankar. And perhaps 40 years ago he made the pilgrimage to Rashbehari Avenue in the bustling Gariahat district. It is his sweet-toned purchase his son now plays. Another coincidence. Pinky’s tuned percussion instruments were made by Muktu Das, now based in Tollygunge, likewise a district in south Kolkata.

Niladri opened his solo with two movements in Shri or Shree using them to introduce his sitar’s range. The opening alap movement explored the instrument’s high- and low-voiced registers and his powers of controlling and sustaining notes. Ten minutes or so in, he showed off its mid range. Jor, a movement which introduces unmetered rhythm, concluded this segment. A minute later, rhythm began. It came in the form of the dhamar, a tāl and taal rhythm cycle usually associated with the pakhawaj (double-headed drum) but here memorably expressed on jori. It is a 14-matra (beat) cycle in a 5-2-3-4 pattern, with some matras getting Pinky hand-claps. Its mixture of gunslinger sitar and quick-witted slow passages filled the senses – but not like a night on the mountain.

A review shouldn’t be a set list. Two more repertoire items must do. For some fifteen minutes in the second half they explored a work in progress. Called Tilak Nat, it is a pairing of ragas Tilak Kamod and Nat. (Afterwards, Niladri explained privately, he’d felt like trying out his composition in public.) When it is worked through and thoroughly road-tested, it is going to be a signature composition for him. Shankar’s Tilak Shyam went through a similar process, I observed. The pretty closing piece, set in Bhairavi, recalled a mood the English guitarist John Renbourn was wont to create, with Pentangle but especially as a soloist. This had Pinky’s rhythmic uplift, though. It went through tempi, cheekiness (a western classical quotation, almost Vilayat Khan style) and ended with a search for the lost octave, way down the fretboard, almost into the sound hole, Eric Clapton-style. To conclude, Niladri Kumar is, head and shoulders, the most exciting talent to burst into my sitary consciousness in well over a decade. Don’t miss him.