The Rite of Spring – Seeta Patel Dance

The Rite of Spring

Seeta Patel Dance

Sadlers Wells, 13 March 2023

Reviewed by Pranav Yajnik

Photos: Foteini Christofilopoulou

Stravinsky’s (mythically riot-inducing) The Rite of Spring has been a staple of ballet and contemporary performance since its creation. The original ballet tells the story of a mystery-cult celebration of spring by a group of initiates; from this group emerges a chosen individual who must sacrifice themselves to death by dancing.

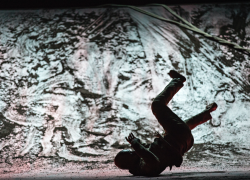

Seeta Patel’s interpretation of The Rite of Spring varies the story: the chosen one is not sacrificed but deified; yet death still stares out from the chosen one’s stony eyes – for what is apotheosis if not the end of a mortal life to become a god? Seeta Patel drives bharatanatyam’s pounding footwork into Stravinsky’s percussive score to underline the inevitability of the story. The stage is pleasantly full of dancers and the choreography has the greatest impact when there is a mass of movement in synchronicity or counterpoint, with patterning on-stage forming and dissolving at every moment. Powerful too is the harnessing of bharatanatyam’s conformity and obsession with geometry to eerie effect – for example, the group’s invitation to the chosen one to become a god is by its repeated insistence more a threat; the prostration of the group before the god briefly becomes a path of thorns. The way to godhood seems strewn with trouble.

The lighting scheme is clean and bold, using the warm hues of the costuming to good effect, and it is a treat to have the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra playing from the pit. Patel chooses to break Stravinsky’s musical piece in two and introduce a dreamlike new scene where the chosen one is awakened from sleep. The imagery in this piece is particularly striking as he is coaxed back to waking while the circular, floaty vocals of Roopa Mahadevan echo the fairy dust wafting around the stage and contrast beautifully with the onward velocity of the surrounding orchestral score.

Before The Rite of Spring, the audience is presented with a solo bharatanatyam piece by Patel herself. Entitled ‘Shree’, it linked thematically with The Rite of Spring by presenting nature and its destruction. However, the piece suffered from a few practical problems. First, the lighting scheme was – particularly in the beginning – very dark, with the result that the movement and indeed Patel herself were impossible to see. Second, as a mainly expressional piece, it was lost in the vastnesses of Sadlers Wells: if it was already difficult to catch the subtleties of Patel’s changing expressions from halfway down the stalls, it must have been impossible from the higher tiers. Third, the aural element of bharatanatyam in the form of ankle bells (as with many other classical dances) explains many of the limitations of the choreography in a pure classical piece; and without them some of the choreographic choices gave rise to awkwardnesses that seemed should have been resolved. However, the staging of the piece was striking with three musicians (who were all excellent, Vijay Venkat’s flute standing out in particular) seemingly suspended in mid-air behind the dancer, and projections that presented the imagery of the piece on a macro scale.

The Rite of Spring ends on a reflective note, showing Patel as a choreographer who is unafraid to risk sacrificing the traditional big ending for something more thought-provoking as the cultists disappear behind the chosen one, who is left rather fossilised by his transformation. It is one more subversion, a nice turn for the unexpected, which continues Patel’s demonstration of her understanding of how to evoke a response from the audience. Others would have balked at the prospect of successfully carrying off such a symbolically important piece such as The Rite of Spring; Seeta Patel has done it with panache.