Xenos

Xenos

Akram Khan Company

Sadlers Wells, London

2 June 2018

Reviewed by Sanjeevini Dutta

Akram Khan is a household name for anyone with even with a passing interest in dance. In his two decades as a dancer choreographer he has a string of productions to his credit. He has danced with French ballerina Sylvie Guillem and actor Juliette Binoche; toured extensively across five continents and been taken into the heart of the ballet world by choreographing the old time favourite nineteenth century classic Giselle for English National Ballet. Moreover, he has achieved this astounding success with his base training in a technique completely outside the established classical ballet world, in the South Asian dance style of kathak. Admittedly it was his subsequent training in contemporary dance that allowed him to genre bust.

Akram’s crisp, precise movements, simultaneously with attack and fluidity, make him a standout performer. His exposure aged twelve to the great theatre director Peter Brook gave him an early grounding in theatre that came ultimately to define his style. His first solo full-length production Desh, based on his homeland and his own family’s history woven together into an excellent script, with Tim Yip’s (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) design, established his reputation as an incomparable storyteller. The trajectory has been ever upward with artistic and commercial successes: Vertical Road, iTMOi, Torobaka, Until the Lions, all produced over the last eight years.

Therefore, the news that Akram was working on his farewell solo full-length show drew great interest from the dance world, the public and the media. BBC Radio 4 produced a thirty-minute process interview with Akram six weeks before the première due to take place in Athens. A short excerpt was performed at the Darbar Festival at Sadlers in November 2017.

Xenos had a nine day run at the Sadlers Wells and I caught the fourth night. The opening is promising: a singer and a percussionist in a space set up with rugs and chairs for a soirée or baithak that is also a dug-out shelter. A dancer staggers on the stage and proceeds to dance with breathtaking sharpness and grace, recognisable kathak repertoire; but his movements appear to be sawn-off and the music suddenly grows silent as if the power levels have dropped. The sounds of artillery fire suggest that the war theatre is not too distant and will at any point bring the performance to a close. The voice of Aditya Prakash singing warm and lilting Vaishnava bhajans and Sufi kalams contrasts with the loud and persistent mridangam beats belted out by Manjunath. There is an element of fragility and unpredictability in the dancer’s movements, as his eyes are distracted and far away. His movements fracture, often bringing the dancer to his knees.

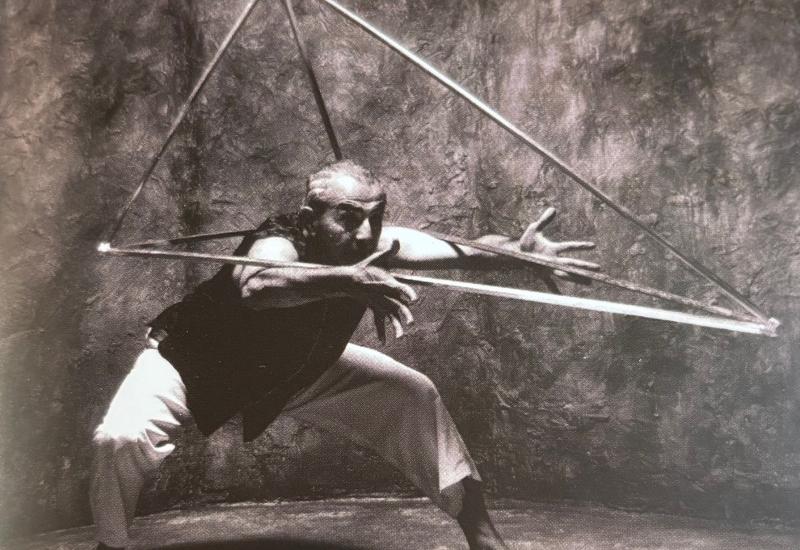

An explosion engulfs the stage and we see the entire stage with props sucked up as in a vortex, the chairs and rugs lassoed by ropes, to reveal a bleak dark place in ghostly white light. The dancer’s ghungroo bells are unwound and become a ball and chain, shackles, or poles for traversing through the thick mud of Northern France after persistent rain. These transform into the ammunition belt of the infantryman – a brilliant use of props.

The stage is again plunged in darkness and the strike of a single match has to illuminate the space. We hear the voice of the dancer, ‘This is not a war, this is the end of the world’. This is such a grand, eloquent statement, that the production will struggle to deliver it.

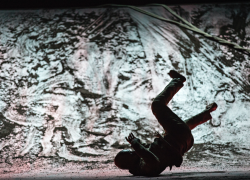

The next scene reveals a massive embankment that goes across the whole stage. Bathed in a red light with dark blotches of mud, it creates a dramatic and sumptuously textured backdrop to Khan’s ever-morphing silhouetted shapes. The musicians are revealed high up and the three Western musicians, soprano, saxophone and double bass are a ghostly presence, joined later by the two Indian musicians.

The solitary figure of Khan on top of the embankment, against a vast black horizon is chilling. It is symbolic of the loneliness and isolation of the soldier.

The content of this longest section of Xenos consists of Khan’s explorations on the ridge where we see him saluting, laying down wires, ropes, body shuddering and being thrown about at the sound of gunfire. We see him tentatively touching a device which looks like a gramophone with a brass trumpet that blares out orders; it later becomes a searchlight to seek out any fleeing soldiers. The names of the dead Indian soldiers are called out dully.

There is also a section where Khan gathers up the earth to make a pile as if holding his sanity by an act of creation amidst the devastation all around him.

The finale sees the dancer caked in soil as he tries to climb over the steep embankment and the mud that rolls down to submerge his body. The explosions grow in intensity, with the final dramatic conclusion of a rain of shells which starts with ones and twos and finally a ton of shells or mudslide that engulfs, to the strains of Mozart’s Requiem.

Akram Khan’s vision is epic, his ambitions bold. While his dancing continues to command the space and transfix the eye, the production falls short of achieving the mythic status to which it aspires. The imagery is fragmented and the pieces of choreography do not tie up to create a larger whole. There is a lack of narrative arc with too many individual ideas that ultimately do not illuminate the human condition.

Perhaps the remembrance of the First World War, a subject wrung dry after two years of marking the centenary (Lest We Forget, Akademi’s The Troth) lacks conviction. Or the fact that it tries too hard to embrace a universal stance, yet fails to reference the turmoil of wars that rage a century on . One is left with powerful imagery: the body that is tossed about and wracked in pain and torment; the stunning set and lighting; excellent musicians, but given all these elements, the performance does not evoke the apocalypse of ‘the end of the world’, and does not engage this reviewer emotionally as the intellectual content in the final analysis does not cohere.