Line & Verse: Erasing Borders Dance Festival 2025, Day One

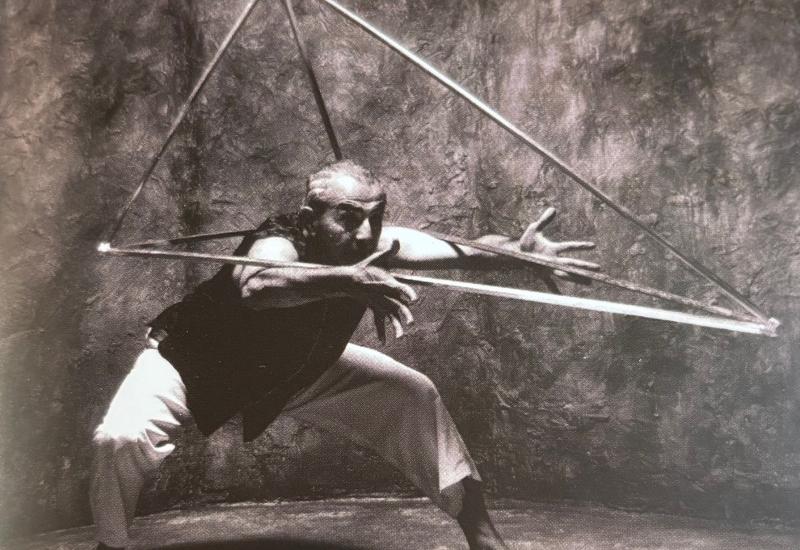

Photos: Nir Arieli/Erasing Borders Dance Festival

The Erasing Borders Dance Festival Day, presented by the Indo-American Arts Council, opened with a diverse evening of Indian classical dance that highlighted both emerging talent and veteran artistry. Across bharatanatyam, odissi, kuchipudi and kathak, the program revealed the breadth of these art forms.

The evening began with the Nrityanjali Dance Ensemble, under the direction of Ramya Ramnarayan. A trio of young bharatanatyam students opened with a vrittam (sloka) in praise of Lord Shiva with enthusiasm and clear potential. With only three on stage, a tighter formation would have focused the audience’s attention. They were followed by seven bharatanatyam dancers in a Natesa Kautuvam set to ragam Hamsadhwani. The choreography was inventive, well-rehearsed and made full use of space. Cleaner finishes to footwork phrases would have further sharpened this strong presentation.

A broader issue throughout the night was the lighting, which often cast shadows on dancers’ faces. In this work, the lights dimmed too soon, robbing the audience of the chance to savor a beautifully sculptural final tableau.

Next, Trina Sarkar, an odissi dancer based in New York City, presented a Pallavi, a pure dance item which translates to “blossoming” or “unfolding”, also set in ragam Hamsadhwani, choreographed by legendary Guru Kelucharan Mohaptra. Sarkar distinguished herself with commanding stage presence and assured technique. She expertly showcased odissi’s lyricism with her ability to contrast powerful footwork with delicate movement. At moments, her alignment with talam (rhythm) wavered, and while she began with expansive stage coverage, the presentation later settled too heavily at center stage. The jugalbandi section, traditionally a vibrant exchange between dancer and musicians, lost much of its vitality in the absence of live accompaniment. Nevertheless, Sarkar’s expertise offered a captivating glimpse into odissi’s grace and dynamism.

Washington DC based Kalanidhi ensemble followed with Ananda Tandava, a kuchipudi work embodying Lord Shiva’s cosmic dance as Nataraja. With five dancers, the work opened with a vrittam in ragam Keeravani, building momentum with coordinated movement and an explosion of energy in the form of an exhilarating jathi. Even as the group thinned to two, the intensity remained, culminating in a solo jathi that earned spontaneous mid-performance applause. Sculptural poses, particularly those evoking Shiva clad in serpents, were striking with excellent use of limb extensions, while duets conveyed the cosmic vigor of Shiva’s dance. The choreography was vibrant and expansive, making the audience’s eyes dance across the stage as dynamically as the performers themselves. The finale brought all five dancers together in seamless coordination, leaving no doubt about the ensemble’s command of the art form, discipline and rehearsal.

Yet the spoken introductions to the work, as with others that evening, would have benefitted from greater preparation and precise pronunciation. In Indian classical dance, these contextual frames are critical to honoring the integrity of the art forms.

The evening’s penultimate group came from the Chitresh Das Dance Company, a kathak troupe from California, presenting Invoking the River. Choreographed by Charlotte Moraga with music by raga pianist Utsav Lal and tabla accompaniment by Nilan Chaudhuri, the piece, as the programme notes explain, seek to explore “the confluence of history, mythology and environmental changes on India’s sacred rivers Alaknanda, Ganga, Kaveri and Godavari”. The opening was visually striking: one dancer fixed her gaze on the audience as three traced fluid, rippling gestures with their arms. Smooth upper-body movements paired with traveling footwork evoked the rivers’ flow, and moments of stillness effectively marked rhythmic climaxes. A solo vignette stood out: a dancer embodying a river used mime to portray being trapped, moving through confusion, desperation, determination, and release. This abhinaya arc was deeply moving and beautifully executed.

Yet conceptually the piece was murky, with the individuality of each of the four rivers never fully realized. The ensemble lacked unison in places, and technical choices, such as the absence of floor microphones and excessive blackouts drained momentum. The finale, involving white and blue strips of fabrics laid diagonally across the stage proved distracting, even leading to trips in exit choreography. Stronger without this device, the dancers’ bodies alone were fully capable of embodying water’s fluidity.

The evening closed with the marquee performance of Priyadarsini Govind, one of bharatanatyam’s most celebrated artists. Over the course of five works, she demonstrated why she is revered worldwide.

She began with her signature Devi, the Divine Mother, weaving together Sanskrit verses on the Divine Goddess. Circling the stage with commanding presence, she heightened intensity by drawing physically close to the audience. In this piece, Govind’s expressive use of breath, from the labored inhalations of Kali to the serenity of Parvati, was breathtaking (pardon the pun).

Lighting for Govind was markedly improved. During her depiction of Ardhanarishvara, half the stage bathed in blue and half in yellow, subtly and powerfully reinforcing Shiva and Parvati’s duality.

Her Aadum Chidambaramo in raga Behag celebrated Nataraja’s cosmic dance, intertwining jatis with melodic lyrical verses (sahityam). This piece included a prelude from the Thirumandiram, with the composition arranged musically by Rajkumar Bharathi. With grace and agility, Govind expertly embodied Shiva as both powerful and playful, sculptural and dynamic.

Dasamukhi followed, in which Ravana, the antagonist of the epic Ramayana, laments his downfall through the voices of his ten heads. He should have been remembered as one of history’s greatest emperors. Instead, his inappropriate desire for Sita led to his undoing. Govind portrayed Ravana’s inner turmoil with remarkable subtlety. Each of his ten heads registered a distinct emotion including weariness, sadness, shame, astonishment and meditation. Through the smallest shifts of gaze, expression, and posture, Govind created transformations visible even to the farthest rows. Ravana’s inner lament was conveyed with heartbreaking clarity.

Her penultimate piece, Samayam Ide Rara, a popular Javali also in Behag, introduced humor with remarkable success. As the heroine feigned sorrow to send off her husband while plotting a clandestine meeting with her lover, Govind’s exaggerated crocodile tears and comic timing elicited genuine laughter, a rare feat in bharatanatyam.

Govind’s genius lies in her dancing, of course, but also in her ability to contextualize the work. Her brief explanations between pieces illuminated each piece with clarity and warmth, enchanting the audience. Govind’s performance was a display of technical brilliance and emotive depth and a reminder of bharatanatyam’s capacity to contain reverence, playfulness, pathos, and humor all within a single artist’s repertoire.

She closed the evening with another signature piece, the Marathi abhang, Vrindavani Venu, in praise of Lord Vitthal. With the use of expansive movements punctuated with Govind’s signature shoulder blade isolations, she established a sense of reverence, joy, and peace, bringing the first day of the festival to a close with unforgettable artistry.

The 2025 Erasing Borders Dance Festival began as a night of contrasts: younger dancers finding their voices, ensembles pushing energy and coordination, and a legend reminding us of the heights these art forms can reach.

Editorial note: We are retaining US spelling conventions for Line & Verse