Reflection on Sadir, a forgotten heritage

Dance Dialogue: Glittering Tales: Dancing for Rajahs, Nawabs, and the Officers of the Raj

Swarnamalya Ganesh and Chitra Sundaram

25 June 2019

Asia House, London

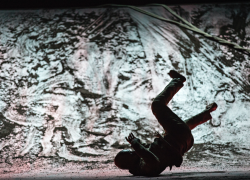

SADIR: Dancing for the Rajahs, Nawabs and the Officers of the Raj

Swarnamalya Ganesh

30 Jun 2019

LSO St Luke’s, London

#Akademiat40

‘And finally, we are here to destroy myths’. Dance artist and academic Chitra Sundaram, who curated the Sadir Series for Akademi, introduced Dr Swarnamalya Ganesh to London with this promise; and over the course of a lecture demonstration on Tuesday 25th June and a performance on Sunday 30th June, it proved to be surprisingly spot-on. For the first ever time, audiences in the UK had the opportunity to watch Sadir in its most authentic incarnation. Though it is popularly described as the precursor to bharatanatyam, Sadir was the prolific form of dance that reigned over South India; multicultural, multilingual and multi-faceted, it formed the rich musical and artistic heritage from which bharatanatyam has been selectively carved in modern times. Though the etymology of the term Sadir is unclear, it appears across several languages including Persian, Urdu, Sanskrit and Tamil and researchers conclude that it alludes either to a gathering in honour of an important person, or the announcement of their presence. This is the first clue to its rich history; unlike bharatanatyam which is promoted as both ‘classical’ and Hindu, the beauty of Sadir lies in its multiplicity of influences, audiences and musical genres.

Swarnamalya began her presentation at both events with ‘Dora Salaam’; singing along with the musicians, she entered the darbar area with hand respectfully at her forehead, gesturing a salaam to the imaginary King present amongst us. This immediately went against some intuitive prejudice I had absorbed in my bharatanatyam training; I associated something this Islamic with kathak rather than bharatanatyam. It didn’t take long however for this connotation to unravel; the Sultanate courts of the Mughal Carnatic in the 18th century had a significant influence on the artistic activities of the time, and the Nawabs of Arcot were huge patrons for dance and music in southern India. Swarnamalya also performed a thumri (romantic poem) composed in Deccan Urdu, and demonstrated Sadir’s adoption of Sufi music under the patronage of Sadathullah Khan during the same century.

The musicians that accompanied Swarnamalya exhibited a thrilling range of expertise across musical genres and languages. The ensemble consisted of a vocalist, mridangist, mandolin player and harmonium player and in this one evening they sang in Urdu, English, Telugu, Tamil and dipped into Carnatic, Hindustani, Celtic and Sufi melodies. Swarnamalya was keen to emphasise that this was only a small cross-section of the musical variety that flourished in southern India at the time; it was not uncommon to have pianos, french horns, clarinets and fiddles playing alongside the rudra veena and harmonium.

All of Swarnamalya’s pieces were delightful in one way or another; a pada varnam composed by the well-known Tanjore Quartet gave us a glimpse into bhoga, the courtly aesthetic rooted in pleasure and indulgence; a ‘company javali’ from the 18th century combined English and Telugu lyrics and was just one example of the many bespoke compositions made for specific officers of the Raj. Composers that are revered for their bharatanatyam creations such as Kshettraya and Muthuswami Dikshitar were very much a part of the world of Sadir; the last piece Swarnamalya performed was a Carnatic arrangement of a Celtic melody called a ‘Nottuswaram’, and she informed a surprised audience that Dikshitar composed 34 of these marching-band-inspired fusion tunes. I couldn’t help but wonder then, which other parts of our dance heritage have been ignored in the propagation of a national, classical dance form.

But even more than all these revelations about repertoire, I was most struck by just how endearing Sadir was. Devoid of the physical rigidity and performative formality of bharatanatyam, it was a joy to watch the ease, pleasure and responsiveness with which Swarnamalya danced. She communicated directly with us and the musicians, joined in with the vocalist when she felt like it, and executed abhinaya without fuss and frills. I looked around at the audience often and confirmed that I was not the only one completely charmed by her; unlike bharatanatyam, Sadir felt accessible and wholly entertaining. Having said that, it was clear that much of the effect was created by Swarnamalya herself, who was an excellent performer and had an intuitive mastery of the music. She explained that there was no ‘choreography’ as such, but much of the performance rested on manodharma (improvisation). In order to achieve these organic interpretations on stage, she explained that performers must be musicians first and foremost, and dancers later. Training is lifelong and nurtures the practitioner’s imagination, performative energy and improvisational capacity; training is not about mastering items of repertoire.

In the modern context, bharatanatyam is a dance form. So as dancers, we train our physicality to its maximum, we dig into the formal technique to perfect it, we experiment with choreography to find innovation. But there still remains a pull in what feels like an opposite direction. Somehow the facial expressions are still paramount, somehow we need to spend just as much energy learning the music, somehow it’s still not necessarily about virtuosity, somehow it’s still all about the performer’s charm rather than the choreography, somehow the shape of our hands remains just as important as our core strength, somehow it still needs to be facing the front and telling stories.

This tension is something that I suppose most of us are used to, but watching Sadir was enlightening; it brought home to me what bharatanatyam actually came from, and why it still feels like I’m training in more than just a dance form. Swarnamalya did not just dance; Sadir demands that the performer is a musician, a story-teller, an improviser, an actor, a dancer, and ultimately somebody that entertains. Don’t our modern (and western) delineations between dance, music, theatre etc impoverish our understanding of what we do?

Modern day bharatanatyam was constructed as a nationalist response to the colonisation of Indian culture. Sadly this means that bharatanatyam hasn’t retained the multi-cultural, cosmopolitan and responsive culture of Sadir and I’m craving to learn more of what has been deliberately forgotten. It’s not my place or desire to suggest that India reforms its memory of colonisation but I think it’s imperative to celebrate the innovation of artists in that time, in responding to those multicultural environments with such creativity and openness. I’m also curious to understand how Swarnamalya reconstructed an art form from the memories of elderly ex-practitioners; the complexities of that process seem overwhelming. When recounting my experience of her performance to a friend, they exclaimed ‘man, she needs a documentary made on her!’ Now, wouldn’t that be fascinating, I thought.

Photo credits: Simon Richardson

Glittering Tales was presented by Akademi in association with Asia House and SADIR in association with SAMA Arts.

Both events were supported by ACE; London Community Foundation through Cockayne fund; Indian Council for Cultural Relations; The Nehru centre and High Commission of India,