Race and Class: Lessons from the Festival of Thaipusam.

Sooraj Subramaniam recalls a childhood incident in his classroom in Malaysia which had all the hallmarks of racist abuse. How did he respond then and what would he tell his young self now? The complexities of race, class, wealth and power structures need to be decoded and each one of us has to stand and be counted. The writer vows to make a start.

'Your god holds a spear? And rides a peacock?' – the teacher interrogated the fourteen-year-old boy.

He nodded, looking at his feet.

My heart thumped loudly, sensing that she was taunting him.

I was in Form 2, and in an English lesson. We’d been assigned to share stories of cultural customs or festivities. My classmate was second-generation Malaysian, of Sri Lankan Tamil background. Unaccustomed to speaking in public, and further tripped up by the convoluted grammar of English, his explanation had been succinct: Hindus celebrate Thaipusam by carrying heavy things to honour the six-faced god Muruga who holds a spear and rides a peacock.

That’s when the teacher interrupted him abruptly.

'Cat got your tongue?' she posed, dragging out the silence.

She went into a brief divertissement to explain the feline expression. Then she returned to the still-standing boy and clawed in: 'If your god is so powerful why does he need a weapon? True or not?' she dug about the room.

I forget her name. She’d once before giggled with us about her time as a student in England, running around in short skirts. She was progressive; I liked her. She was also Malay.

Not getting a response from the class, she turned to the boy’s neighbour, also Tamil, presumably Hindu. 'You also don’t know why your god carries a spear?'

Stupid fellow, say something! I thought.

The boy remained mute.

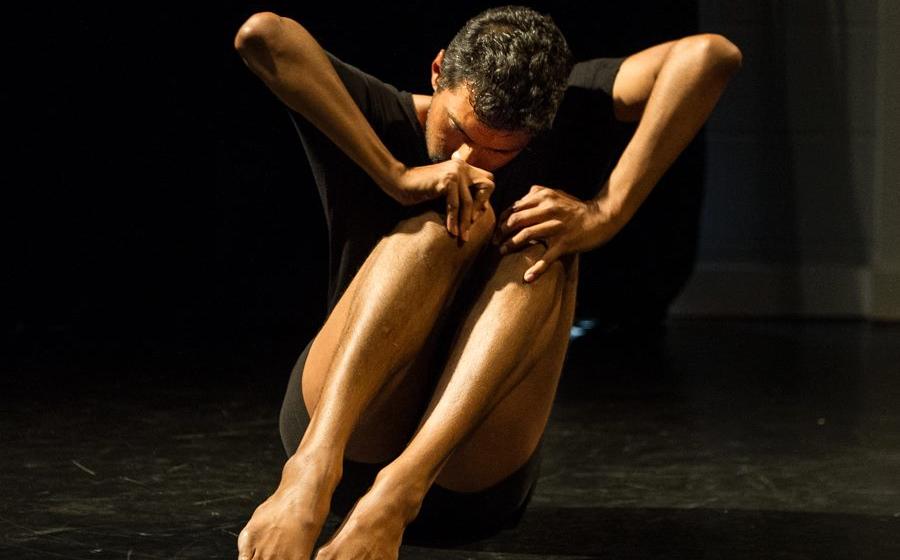

Carrying Kavadi Thaipusam | image credit: Mshahrazif / CC BY-SA https://creativecommons.org/

Thaipusam, which gets international coverage, has been around for generations. It is a Hindu festival of the Tamil community and involves one of the biggest processions of devotees in Malaysia; people walk miles from the Mariamman Temple in the heart of the city of Kuala Lumpur to the Batu Caves Murugan temple.

None of this information would have been new to the teacher. I know she saw the boy for the colour of his skin, for his religion, for his clumsy accent, for his rowdy exterior; for his devotion to an ancient tribal god dismissed as heathen in her narrative.

The plaything being unresponsive, the cat grew tired. The boy was told to sit down. We turned a page and moved on to something else.

*

I grew up in a Malaysia where racism was institutional, systemic and permeated all levels of society; where it meant that access to favourable bank rates, business loans, university positions, and government posts were calibrated by race; where it meant that three generations on you were still a migrant and were being reminded to be grateful; where it meant you could be friends, but entire racial groups were viewed with suspicion and distrust; where it meant that racial slurs were flung about casually: kafir was often spat at non-believers, and keling—some pejorative remnant from the colonial industry of indentured labour—was reserved for the dark-skinned Indian.

My parents believed that an education, in English, would open doors to a better life. A life where my sister and I would overcome race and revel in multicultural, colourblind bonhomie. I’d truly believed that the English teacher shared this egalitarianism.

But on that day I was unable to iron away the feeling that she was coming for me next. I was a good kid: side-part, starched shirts, always did my homework. But I was also Indian and dark-skinned.

If I’m being honest, I’d more potently feared my classmate, and not just that day but for all the time I’d known him. In an eagerness to please, I’d despised him for dragging us all down.

How quickly had I consented to distancing myself from Thaipusam and the proclivities of the devout:

The devotees fast for weeks ahead of the festival; some shave their heads. They walk bare-footed from the temple of the matriarch goddess Mariamman bearing kavadi (literally burden) in the form of small shrines or pots of milk as tokens of their penance to Muruga. The hardier undergo body modifications: common examples are the cheeks or tongue impaled with little spears. The most grueling of the feats involves pulling large chariots, usually harnessed to people’s backs by ropes, or more terrifyingly, by hooks through the skin. Many devotees go into trances. Most come out of the experience feeling rejuvenated, with no apparent pain or infection.

My family, however, professed a type of Hinduism filtered through the prism of high culture, sublimated through classical dance and music, and propped by lofty discussions on philosophy. No processions or penances for us, thank you very much.

In a country fraught with race politics if you behaved ‘brown’ you could only expect to be treated as such. I’d found my classmate inept for his inability to string a proper sentence in English. I despised him for hanging out in those Thaipusam-type cliques. I’d refused to converse with him in Tamil because it was often seen in Malaysia as the language of the poor, not knowing then that it was the system itself that perpetuated a large disenfranchised Tamil underclass.

My English teacher had displayed a spectacular abuse of power when she attempted to shame my classmate. She had used his religion and culture to other him. In wanting to survive I’d co-opted the same slippery politics to direct my derision at him.

The rest of my adolescence was a blur of oblivion: of dancing and good grades and the prospect of a future abroad. I left to go to university and never returned to live in Malaysia. I can safely say that since then my encounters with overt racism have been fleeting.

I put this down to the privilege of passing: I am educated in the mode of the dominant culture. I speak the language of the majority, and I can switch codes and accents with ease. I am a struggling artist, yes, but I have the arsenal of high-speak. I have the privilege of choice.

But one fine afternoon the world finds it fit to remind us that we don’t all of us pass. That it is not sorry that it sees difference, and will use that against us. That despite being a world citizen the emphasis remains 'where are you from'. That it takes an Australian passport to wave away the police at the French border. That 'madrasi' is packed with the same sting as 'curry-muncher'. That despite the weight of supposed antiquity and sophistication the classical dance that I practise is 'fancy fingers' and 'foot clapping'.

Still, I was relatively unscathed, that day and afterwards. What mobility did Thaipusam boy have? I will never know how he fared. His father was a barber, working out of a shack he’d built on a bridge over a monsoon drain.

*

I am a-religious. Issues of faith fluttering around Indian classical dance are swatted away with ‘artfulness’ and ‘transcendence’. While others sweat through the procession during Thaipusam, I stand under soft lighting explaining away the messy rituals of desire and devotion as necessary inconveniences of the human condition to experience art. Enough that I ruffle through the pages of poetry without having to believe in these things myself, I am able to self-indulge, obliquely, in the beauty of metaphor.

But the world is fissured, and heaving in a manner quite unlike anything this generation has so far experienced. The coronavirus pandemic coupled with global anti-racism protests have exposed our exercise of wounding each other indiscriminately. These experiences, debilitating and rousing equally, spotlight the urgency of other conflicts we constantly enact: against nature, against fellow humans, against ourselves.

I often feel impotent—mind adrift, words futile, actions limp—against the goliath that is some system of oppression, deep-rooted, far-reaching, seemingly impossible to weed out. My angst is trained on rogue individuals on social media—indignation turning into virtue-signalling pettiness—and I think I’ve accomplished small victories towards fixing the system. Sadly, there is no appeasement from stabbing in the dark. Where I expect resolution there is only a chasm of anger, resentment and disappointment.

How about if I turn the enquiry within? How about I weed out the oppressions in my own mind? Sift through my prejudices and call myself out for my shortcomings? This sounds moral and righteous, and more importantly, feasible. But no sooner do I unpack one less-than-honourable action than I seem to commit another, worse, one.

So, I prevaricate.

*

Honestly, I’m a coward: unable to change systems, tired of replaying arguments, too afraid to examine my demons. So, I turn to comfort routines. I view the protests from the distance of my television screen while chomping through my dinner. Confused and listless as I claim to be, I am able take respite in my yoga and dance practice.

But the guilt prickles away. I’ve replayed that classroom scene many times, imagining myself, if not snubbed by afterwit, going to my classmate’s defence.

Here’s what I’ve recently realised: that I didn’t need to jump in and be a hero; he didn’t need saving from the teacher. Rather, the rogue individual that needed battling was me. That by remaining silent I had fed the apathy in my mind, abetted chauvinism, and stood complicit to an injustice. That by painting myself a good person I had thought myself beyond fighting.

I am not good at taking vows, but I’ll begin by asking my classmate forgiveness for having remained silent. For having taken so long to realise it was I, not the teacher, who betrayed him. For dancing rituals of smearing holy ash but for begrudging him the same bhasma marked on his forehead.

It is still transcendence that I seek. But not into the unknown, not for anything as grand as enlightenment. Rather, I only want for us to be moved into considering if our actions against others are honourable. I want good people to stop being a part of the problem and start being a part of the solution.

The path for me then—even if only for my sanity—is the middle one, where I find balance between dusting out my heart and mind, exchanging thoughts with friends, seeking solutions within communities, and using what is at my disposal—my art, my voice, my influence, what little sphere it makes—to call for a more just world.

To my English teacher I would probably say, that Muruga is six-faced for the elements five and the mind within. That to ride a peacock, brief though the flight, is to be powered by the beauteous and the impossible. That the spear proffers the courage to impale the demons in the heart. And that power comes not from being all-knowing but from a willingness to confront, to change, and to stand with others against the unjust.

Sooraj Subramaniam

18 June 2020

With much thanks to Meera Vijayan and Sudheesh Bhasi