Reflection: Lives of Clay

At Pulse we have been discussing the role of the reviewer: is it to judge, comment, provide feedback and improvements, or to help audiences interpret and to spark their interest?

In fact, it can be any or all of the above. Whilst ‘Reviewer’ suggests that to some degree the writer is ‘free of biases’ through expert knowledge, our reviewers are mostly fellow artists rather than professional ‘critics’.

Thus we are naming some of these pieces ‘Reflections’, which better describes the responses of fellow artists to a performance.

We were interested in how the show impacted them. Did the performance raise questions, did it take them on a journey? We are aware that each writer comes from a unique perspective – they may be very familiar with the technicalities of a style and the culture from which it derives, or may be coming to see the show with no prior exposure to classical South Asian dance. For the writer to share their own background is helpful for the reader to understand the writer’s frame. The ‘reflection’ then becomes more of a ‘dialogue’ than a ‘report card’.

Sanjeevini Dutta, Editor

Lives of Clay

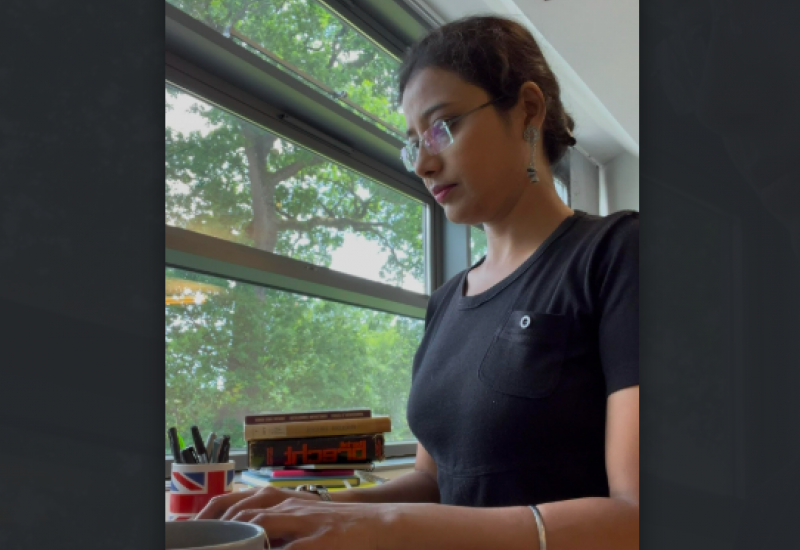

Vidya Thirunarayan,

Art Park,

Serendipity Arts Festival,

Panjim, Goa,

December 2023

Photos: The author

As the audience walk through the park, they are drawn towards an unusual circular enclosure built with a metal fence. As they take their seats around it, they notice that the space is strewn with gunny bags, bricks, pots, sand, clay and other materials often found in a construction site. Inside the enclosure are platforms arranged to create different levels and at the top of this structure is a potter’s wheel. The performer, clad in a simple cotton sari enters this arena through an opening in the metal fence. She climbs her way to the top, takes a seat and skilfully starts making a pot at the wheel with impeccable precision as the whirring of the wheel fills the air.

Vidhya Thirunarayan presented her work Lives of Clay at Art Park in Panjim, Goa as part of the Serendipity Arts Festival held between the 15th and 23rd of December 2023. Directed by Tim Supple, this multi-disciplinary performance brought together different forms of storytelling with the concept of working with the clay or the earth as the common thread across narratives. The sound design by Alan Burgess, with composer Barry Ganberg, offered a musical context to the scene that was being depicted. Electronic music, ambient sounds layered with a female voice relating the story as the narrator, reciting dialogue as the characters and compositions, along with distortions, formed some of the textures of the soundscape. The set design by Julie Belinda was very effective in drawing the audience attention to the performance space in the midst of a busy and distracted outdoor space.

Thirunarayan uses the language of bharatanatyam to depict the story of Parvati creating a child from the dust and sweat of her own body. This mythological story is interwoven with the life story of Meena, a manual labourer working at a brick kiln. The performer embodies multiple characters, including Shiva, Kama, and Parvati, to narrate the story of the birth of Ganesha; and as Meena, a worker at a construction clay kiln, she uses the the physicality of working with the materials and carrying out actual labour to bring the character to life. One particular scene where she works with clay to depict the scene of Meena losing her child to a fire at the brick factory has a powerful impact: she strikes on the large lump of clay on the floor with a piece of wood, pounds on it with her her bare hands and covers herself in clay as an expression of the the unfathomable grief of a mother losing a child.

As the stories unfolded, I could not help but think about the deeper political question of how class shifts our relationship to what we create. How is an artist making a pot different from a person working with clay in a brick factory? What is our relationship to what we create? Is it the same across class and caste? While Parvati’s expression of rage compels Shiva in resurrecting her creation (Ganesha), back to life, the destitute Meena is left helpless and hopeless in the face of her child’s death. What does creating something mean to someone from the marginalised community in a society where their own lives are not valued?

At different intervals, Thirunarayan breaks character and sits at the potter’s wheel. The stark class disparity that differentiates 'making art' from 'manual labour’ becomes evident in her comfort while moulding clay. As she makes eye contact with the audience, trying to break the fourth wall of the fenced enclosure, a mysterious sense of unfamiliarity sets in. One is left wondering about her unsaid personal relationship to motherhood, labour, creation, grief, and what her own story is beyond the representation of the other and the imagined mythology.

Veena Basavarajaiah is a movement artist: a performer, creator, curator and activist based in Bengaluru. She is known for her satirical look at the darker side of the Indian dance world through her cartoons, under her handle @cartoon_natyam.