Reflection: Aunusthan – A celebration of neo-classical Indian dance and Music

At Pulse we have been discussing the role of the reviewer: is it to judge, comment, provide feedback and improvements, or to help audiences interpret and to spark their interest?

In fact, it can be any or all of the above. Whilst ‘Reviewer’ suggests that to some degree the writer is ‘free of biases’ through expert knowledge, our reviewers are mostly fellow artists rather than professional ‘critics’.

Thus we are naming some of these pieces ‘Reflections’, which better describes the responses of fellow artists to a performance.

We were interested in how the show impacted them. Did the performance raise questions, did it take them on a journey? We are aware that each writer comes from a unique perspective – they may be very familiar with the technicalities of a style and the culture from which it derives, or may be coming to see the show with no prior exposure to classical South Asian dance. For the writer to share their own background is helpful for the reader to understand the writer’s frame. The ‘reflection’ then becomes more of a ‘dialogue’ than a ‘report card’.

Sanjeevini Dutta,

Editor

Aunusthan – A celebration of neo-classical Indian dance and Music

Pagrav Dance Company

10th January 2024

The Lowry, Salford

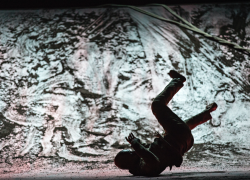

Aunusthan began with the sounds of the sarangi played by Satwinder Pal Singh, followed by the alaap (vocal stretch of musical notes) by Kaviraj Singh; then all seven dancers march onto the stage to sit downstage, a couple facing the back and the rest facing forward. The seated choreography of hand and torso sways and movements was alluring, the dancers’ almost backless blouses modestly covered by criss-crossed lace. The sharp 180 degrees turns swiftly engineered whilst seated were perfectly executed and deserving of applause. This section could perhaps have gone on a little longer with more swift seated turns (loved it!).

Having two tabla players, Gurdain Rayatt and Hiren Chate, who were brilliant individually and together, coupled with the voice and santoor by Kaviraj Singh and Satwinder Pal Singh on sarangi exalted and amplified the music.

Next, formation: all the dancers stand together in a cluster upstage right and Urja Desai Thakore, the choreographer who is also the current teacher for all the other six dancers, stands upstage right. I say current because some of the dancers were initially trained by other distinguished kathak teachers in the UK and India. This section (not one of my favourites), is in a classroom setting where Thakore is leading the class in a rhythmic call and answer. The addition of a dramatic element might have added more to the experience for the audience. To give it an edge I would have liked to have seen a student taking a lead at times – now that would be intriguing.

The grandiose virtuosity of kathak dance and music was exceptionally presented in an hour. However, the dancers did not use their eyes enough to draw the audience into their world. An important aspect of Indian classical dance is the experience of rasa – the emotion that arises when the audience enters the dancer’s world. In my experience by focusing the eyes to the very last row in the auditorium is the way that a dancer can bring the entire auditorium under her/his wings to join in this journey of dance in a performance.

Thakore’s own solo was too short. With her eyes closed most of the time it felt she was almost dancing for herself. I was hoping that she would develop the subtlety of her expressions and draw us into her amazingly meticulous mind, but this did not happen.

The dancers were synchronised to precision, from the sharp turns to arm movements and head shifts. The element of the unexpected came when a dancer would shift the head in the wrong direction or fling the arm out in the opposite way, which happened a few times, and with obvious grins on the dancer’s face with a guilty expression, which totally made it for me. Even Thakore did it at one point and it was beautifully human and fun. More ‘choreographed mistakes’ please!

It was a technically demanding and intricately woven performance: the dancers were focused to the hilt on the perfect technique, rhythm and lightning speed shifts, changing positions and directions – so much so that the human connections with playful disposition was lacking. The playful interactions between themselves to create the feeling of ease and seamless togetherness was missed greatly.

Perhaps the company with all its technical skills and polish does not need to play it quite so safe.

Kali Chandrasegaram is a freelance dancer and choreographer with three decades’ experience of dancing with UK’s leading companies.