It has been a bumper year for the South Asian dance community. We congratulate those recognised in the Honours bestowed by the Queen; and reflect on the achievements of a number of others.

The South Asian dance community can take pleasure in the Honours bestowed by the Queen to three personalities, all linked to kathak: Pratap Pawar (MBE), the guru of Akram Khan, and a great artist and performer in his own right; Farooq Chaudhry (OBE), the impresario whose partnership with Akram Khan propelled Khan to international stardom (and who went on to become creative producer for English National Ballet); and Sujata Banerjee (MBE), the teacher and trainer of BBC Young Dancer category finalist Vidya Patel, and Chair of ISTD. In contrast there was only one musician of South Asian origin, Nitin Sawhney, awarded a CBE. This may be indicative of the solidarity within the South Asian dance sector which can exercise this level of power and influence. Akram Khan himself has been nominated for three National Dance Awards (Best Male Dancer, Best Modern Choreography and Outstanding Male Modern Performance). Our congratulations to all the artists for their drive and ambition to carve a niche for kathak in the mainstream. As we congratulate the artists commended in the 2019 Queen’s Honours list, we would also like to reflect on the next generation coming through.

The Autumn 2018 season was particularly rich for performances by South Asian artists that were not just good but excellent: Seeta Patel’s Not Today’s Yesterday, Aakash Odedra’s #JeSuis, Shane Shambhu’s Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer, Subathra Subramaniam’s Unkindest Cut and Amina Khayyam’s One. The dancer-choreographers tackled big issues of race, identity, colonialism and mental health, amongst others. However, such a list gives no indication to the level of artistry and sophistication of these productions. So let’s nail the fact that these shows had a high standard of dance, good production values and a robust conceptual framework delivered through diverse expressions from humour to visual aesthetics of lighting and use of props and film, a trend that is dissolving the boundaries of artistic disciplines. South Asian dancers have their finger of the contemporary pulse. As noted in the last blog, Darbar Festival completely bypassed the exciting and relevant work being created by British Asian dancers here and now. We hope that 2019 will see some changes to reflect the work of UK artists.

This blog highlights the work of one artist Amina Khayyam, who has chosen to work with diverse communities and particularly with women. For this reason perhaps her work has not had the airing it deserves. This is an attempt to redress the balance and put the spotlight on an extraordinary dancer who has important things to say.

We know that kathak is a storytelling form and therefore it can tell a story, any story. Yet if we take away the mythological narratives, we remove three quarters of the existing repertoire. Amina Khayyam, kathak artist, born in Bangladesh and trained in the UK, has made a conscious decision to keep her dance free of all religious and mythological references. She finds her stories in the lives of marginalised women, and encountering their experiences in workshops opens up lines of enquiry. This takes Amina’s work into new territories and nothing expresses this commitment more powerfully than her re-workings on a show first performed in 2010.

One is inspired by the idea of cyclical time – the first beat of the rhythm cycle is also the final beat. The cycle works on an everyday basis on the turning of day and night, the tides and the seasons, and on the larger scale in the journey of life and in the narrative arc itself. The dancer-choreographer has taken a classical concert set, which begins with vandana (invocation) and amad (entry), establishing the basic syllables; followed by the display of virtuosity in delivering rhythmic compositions of tukra and torah; and finally the expressive abhinaya sections; she layers this existing structure with multiple narratives.

There is a hint of people on the move: the boatman’s song is of the majhi (fisher folk) tradition; the white fabric becomes the boat in which the traveller sets out (could be the flimsy rubber dingy let loose on the waves of the Mediterranean). The dancer’s movements are deep and circular, smooth and stretched as if the kathak form has lost its prettiness and its formal constraint. On the face, fear and uncertainty co-exist with hope and excitement. The dancer is dressed in a steel blue simply-cut long dress, with minimal make-up and no adornment. The simplicity of the costume matches the open gaze in which nothing is held back.

Image credit: Simon Richardon

The music is provided by an orchestra of four musicians: tabla (Debasish Mukherjee), vocals (Lucy Rehman), cello (Iain McHugh) and spoken rhythms (Jane Chan). This gives an immediacy and freshness, allowing for improvisations, although the rhythmic compositions are set. Effective lighting design dominated by blue hues of sky and sea supports the narrative beautifully.

The journey itself, which straddles the technical sections of madhyam and tisra (medium and fast speed), introduces us to characters who are on the exodus. Standout moments are a tukra (rhythmic composition) in which a pregnant woman is convulsed with birth pangs, ending with an infant in her arms; a gun-toting female freedom fighter/terrorist brandishing her weapon with a chilling indifference; an elderly woman struggling to keep up in the long march to safety. The fact that these cameos are delivered whilst the tukra makes its demands of speed and clarity, is indeed a marvel. The dancer has cracked a conundrum – sketching a story with rhythm, bodily stance and gesture within the lightning speed of the sound composition.

Image credit: Simon Richardon

The third section moves into the arrival, the disappointment and lost dreams. The thumri (love song) which conveys the hopes and dreams that persist for the traveller/refugee, no matter how dire the circumstances, and a tarana that is broken; instead of the smooth and joyous concluding item we expect, it stops and starts. Towards the conclusion, suspended microphones stand for the voices of the many, representing the padhant (spoken rhythmic syllables), in which the dancer normally recites the compositions and then proceeds to perform them. Amina uses this an opportunity to let it stand for the voices of the many. The tatkar (footwork) becomes meaningful as it is also builds on the journey metaphor.

The ending unites the dancer with the soil of the earth, the return to the beginning – becoming One with the Universe.

Khayyam’s performance on the final show of the tour at the Library Theatre in Luton seized the heart and the imagination of her audience. She succeeded in communicating the plight of people on the move to make a better life for themselves by subtle and many-layered expressions. The fact that this was done through nritta (non-narrative dance), rather than natya (dance theatre) makes One a milestone moment for kathak. It moved the form forward from one reliant on conventions to that which is being created afresh.

To the artist the most important feature of her company is dramaturgy that is driven by the politics of race. Yerma transposed Lorca’s work from its rural Spanish setting to the inner city. A Thousand Faces addressed acid attack. In contrast to One, these are narrative works. There is an uncompromising commitment to portraying the stories of those in the margins and this mission underscores the artist performance with a genuine authenticity that makes compelling viewing.

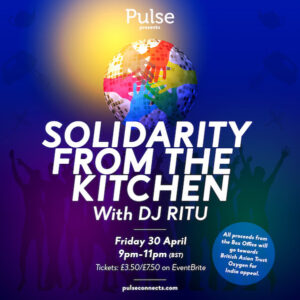

Pulse reviews: