Pakistan’s Music Industry – A Historical Perspective

This article by Arieb Azhar was first published in Pulse #137, Summer 2017.

We re-publish it here on the anniversary of Pakistan's independence, 14th August 1947.

Repression, resistance, Coke Studios and music festivals – musician Arieb Azhar leads us through the vagaries of post-Independence Pakistan.

PAKISTAN, LIKE THE REST of the subcontinent, can boast of a vibrant and deep-rooted tradition of poetry and music. Even though appreciation of refined poetry and music is ingrained in Pakistani society, the state has been inconsistent in its role as patron of the arts and has at times attempted to stifle the free flow of culture. This has not, however, stopped the generation of master musicians and the development of interesting new forms of music in several genres.

Pakistani music is usually categorised as folk, classical, semi-classical (ghazal and geet), Qawwali, pop, rock and contemporary (including electronic). ‘Fusion’ is a newer term widely used for any type of music that combines folk or classical music with electronic instruments or guitars.

I myself am often categorised as a ‘Sufi singer’. The term ‘Sufi music’, just like ‘fusion music’, is also a newly-popular expression. While growing up, musicians who would sing the poetry of the manifold Sufi saints of Pakistan would be simply called ‘folk musicians’. Today, the term ‘Sufi music’ is used loosely to describe all music that makes use of Sufi poetry or terminology including folk.

Great folk music can still be found in almost every region of Pakistan, although local venues in which to perform have become scarce. Sufi shrines and folk festivals continue to be the bastions of the poetic musical heritage of the land, despite being under constant threat from terrorists and extremist sections of society.

The development of the urban-based music of Pakistan, on the other hand, has been much more erratic. From the partition of the subcontinent to the late 70s there were bars and nightclubs in the cities of Pakistan with live jazz and rock music bands, mostly composed of musicians of Anglo-Indian and Goan ancestry but also a lot of Westernised youth from Muslim families. Several notable jazz and rock musicians from the West (Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, The Beatles…) used to travel through Pakistan during that time and many performed in local clubs and jammed with the house musicians. There was also a burgeoning film industry that employed a lot of musicians in its orchestras and provided a platform for several classically-trained vocalists to become popular singers. Radio Pakistan was also a hub of musical activity and source of income for scores of talented musicians.

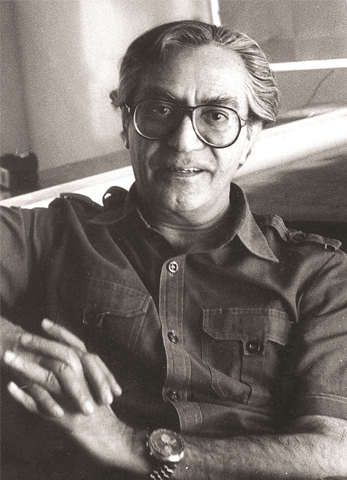

When Pakistan Television came into being in 1964, headed by my father Aslam Azhar, it brought all the great folk and classical music talent into people’s living rooms and gave a platform to several already recognised voices of radio and the film industry, such as Tufail Niazi, Pathaney Khan, Shaukat Ali, Reshma, Alam Lohar, Muhammad Jumman, Faiz Baluch, Mai Bhagi, Abida Parveen, Salamat and Nazakat Ali Khan, Amanat and Fateh Ali Khan, Roshanara Begum, Munni Begum, Malika Pukhraj, Noor Jahan, Mehdi Hassan, Sabri Brothers, Aziz Mian Qawwal, Allan Faqir and many others.

EMI, the major record label, also played a huge role in sustaining the livelihoods of hundreds of musicians, while institutions like the Arts Council and Lok Virsa recorded and founded music libraries.

The big changeover in Pakistan happened when the centre-left populist leader Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was overthrown by General Zia-ul Haq’s military coup in 1977, backed by the USA and Western powers as part of their Cold War strategy. Bhutto had already banned the consumption of alcohol in public spaces in a bid to appease right-wing religious parties, but when General Zia took over he introduced brutal punishments for alcohol consumption and closed down all bars and nightclubs, thus forcing a lot of musicians onto the streets. The film industry, with its orchestras, continued for a while as films became more propaganda-based, selling the new religious patriotic image of Pakistan in order to survive.

If the next eleven years of General Zia were bad for musicians, they were disastrous for dancers. This was the first time that religious radicalisation of society started taking place on a state level. All music apart from selective Qawwali music was looked upon as vice and dance was practically outlawed. Several artists left their profession or left the country, and many became alcoholics.

Some notable pop musicians, however, managed to break through in mainstream media even in the 80s, when the state-run television was mostly promoting religious hymns and patriotic songs. Teenage sister-brother duo Nazia and Zohaib Hassan are shining examples of pop resistance in this otherwise culturally barren era of Pakistani state-run media.

But despite state repression in the 80s (or because of it!), resistance art was thriving on the streets of Pakistan. Artists and intellectuals were gathering in public meetings, study circles and demonstrations and taking strength from revolutionary poets like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Sheikh Ayaz and Habib Jalib. Folk singers in the villages were singing the humanist poetry of the Sufi saints directly aimed against state institutionalisation of religion. Theatre groups like Dastak (which my whole family was part of) and Tehreek e Niswan in Karachi, and Ajoka, Saanj and Lok Rahs in Lahore were organising bold performances on stage and street, questioning the status quo.

The return of democracy in 1988 saw a resurgence of musical activity erupting among the urban youth of Pakistan, although there was a marked disconnect with the pre-Zia music era. My father was recalled by Benazir Bhutto, the new prime minister, to head television and radio, and he started by commissioning a number of cultural, scientific and educational programmes. One such programme was Music 89, produced by the very talented producer Shoaib Mansoor; that introduced a local flavour of rock music for Pakistani audiences in the form of bands like Jupiters and Vital Signs. Soon the band Junoon also came into being and the term ‘Sufi Rock’ was coined.

The '90s were the most thriving period of Pakistan’s urban music scene post-Zia, which saw the advent of private television stations, music channels and FM radio networks hungry for new content. Corporate sponsorship started flowing into the music industry and public concerts started taking place in all the urban centres. This was the period that I missed out on due to my thirteen-year sojourn in Croatia where I was first living as a student and then a musician playing mostly Balkan and Irish music in a music scene completely different from that of Pakistan.

When I returned to Pakistan in 2003, during the ‘Enlightened Moderation’ programme of General Musharraf, I found a new urban generation with material values and no recollection of the pre-Zia Pakistan. I decided to study and use Sufi humanist poetry in my compositions to reconnect with my own cultural source, and since I played my songs on the guitar, I came to be known as a contemporary Sufi musician.

It was in 2008 that the first season of Coke Studio came out in Pakistan, which quickly became the prime music project of the country. The formula of connecting Sufi folk music with rock ‘n’ roll that producer Rohail Hyatt used wasn’t a new one, but as former keyboardist of Vital Signs, the most successful pop band in Pakistan’s history, Rohail knew the ins and outs of the music industry and produced a masterful show. Coke Studio Pakistan became so successful that it prompted Coca-Cola to launch a Coke Studio India as well. Although the project has also been criticised for turning some old folk and Qawwali masterpieces into pop covers, it is undeniable that it has introduced a lot of folk artists and Sufi poetry to younger urban generations. In fact, after nine seasons, the project is still so influential that a musician is not considered mainstream unless he or she has performed in Coke Studio!

But this boom in the music industry was short-lived. The destructive onslaught of terrorist attacks in post-9/11 Pakistan was a new crippling blow to the country’s music industry. In some towns and neighbourhoods, musicians and promoters started receiving death threats from anonymous groups. A cracker bomb attack at the Rafi Peer World Performing Arts Festival in 2008 (while I was on stage!) brought the grand ten-day Arts Festival of Lahore to an end for several years. Corporate sponsors started pulling out of live music events because of security and business concerns. Music channels closed down in favour of news channels as the country went on to a war footing against an unseen enemy and institutions started blaming each other.

Culture and arts are still suffering in a country that is divided in its approach as to how to deal with the menace of terrorism and religious extremism. The internet has provided new space for young artists to share their work, and local music websites like taazi.com and patari.com are trying to create new streams of revenue for artists. But recent pressure by state organs against liberal and secular thought is restricting the free flow of ideas and cultural expression.

Most of the funding for music and culture in Pakistan today comes from foreign donor agencies instead of local government or business enterprise, and although the federal government has had a meaningful culture policy paper drafted, it seems to lack the political will to create a consensus for its implementation.

A positive development that has taken place recently is the burgeoning of several new music festivals being organised by artists and musicians themselves. The pioneers of this new cycle of music festivals are Music Mela Islamabad, which I started with a friend in 2014; Lahooti Melo Hyderabad; Lahore Music Meet; and I am Karachi Music Festival. The Rafi Peer Festival Lahore has also branched out into several smaller festivals. These music festivals help to create artist communities that can work together for the uplift of the music industry. So far Pakistani musicians of all genres that make good money from their music do so by playing most shows abroad.

Art has and always will survive. History has often shown us that the quality of art has little to do with economical and even perhaps sociological conditions. Meanwhile it’s the wellbeing of artists that I’m concerned about, and society that needs to listen to each other’s music.