Shujaat Husain Khan: Legacy of the Maestros™

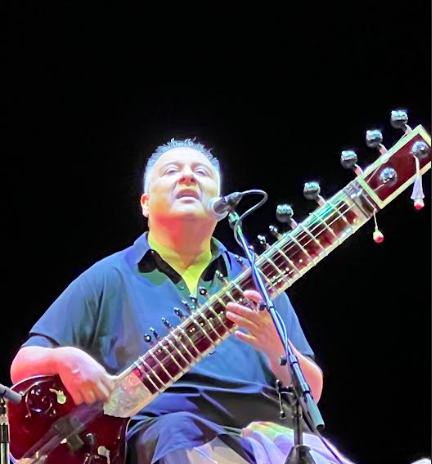

Shujaat Husain Khan

Legacy of the Maestros™

6th September 2025

Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London

Reviewed by Ken Hunt

Photo credit: Paul Coombes

Pinro Media was founded in 2024 by Imran Khan and Ustad Shujaat Husain Khan’s London recital and the one the next evening at Royal Northern College of Music Theatre in Manchester were the organisation’s first concerts in an inaugural series entitled Legacy of the Maestros™. A branding observation: the more gender-neutral ‘Virtuosos’ might’ve been better since virtuoso is widely used to cover both sexes. And I mean who says virtuosa? Mind you, the violin virtuosa Kala Ramnath is a giant of contemporary Hindustani instrumental music, for example.

The Imdadkhani gharana (house and style of playing) is, so to speak, one of royal houses of Hindustani music and Shujaat Husain Khan is its foremost scion. As a sitar virtuoso, no hedging, he is in a class of one. There is no sitarya of his generation – he was born in May 1960 – to compare with him. Having seen Shujaat Khan perform over five decades may help to justify that observation. When I first saw him in the Eighties it was at a concert organised by Jay Visvadeva at John Smith Square. He was one flashy gunslinger. His progress since has been remarkable. Khan is now a senior statesman of the sitar, worthily living up to his father-teacher Ustad Vilayat Khan’s Legacy (to use that word). Talking to Simon Broughton of Songlines after the concert, he said he doesn’t feel the need to compete.

He had two percussionists accompanying on tabla. Shariq Mustafa, who sat to Shujaat Khan’s right, is from the Farukhabad gharana. Opposite him sat Zuheb Ahmed Khan of the Ajrada gharana. What was striking was before a note was struck Khan had no shruti box, no iPad app, no tanpura, no drone on stage. Oh, the blessedness of a recital with no drone sounding on gormless repeat! The following morning I asked about this. He talked about tanpura, its history and his views in far too much depth to include here. He quipped that with six strings and thirteen sympathetic strings why would he need another four? The drone’s absence was entirely liberating. I wish more soloists did it. He added – and I paraphrase – that the absence of drone means the silences and spaces around a note can become integral to a piece’s expression and the exposition isn’t blighted by that intrusive, robotic, bloody ding-ding-ding ding-ding-ding…

The concert began bang on time, rather than running on Indian time, with a pre-recorded introduction about the performers, production and the domestics. On stage, on time, Shujaat Khan quipped, apologising that he wasn’t ‘used to things happening on time.’ He was playing one of two sitars he owns built by the famed Delhi-based instrument maker, Bishan Dass Sharma (1929–2007). He announced Yaman Kalyan. He showed off the sitar’s bright, ringing tones straightaway. For the first two minutes he plucked notes by reaching down with his left hand from above the fretboard. He then switched to more conventionally plucking them from below. It’s one of his thangs.

Shujaat Khan has a compact disc on the Mumbai-based ASA Productions label titled A Tribute to Ustad Vilayat Khan (2010). Its hour-long exploration of Yamani, recorded at Free Studio, Delhi, deserves to be more widely listened to and known. He rounds off a classic interpretation of the alap and jod movements and gat (composition) with a two-minute spoken coda. He reminisces about living in Simla and his father teaching him as a boy and instructing him in the differences and intricacies of Yamani, Yaman, Yaman Kalyan and Yamani Bilawal. Talking to Simon Broughton after the concert, and here I paraphrase again, he said he was more interested in concentrating on a select number of ragas because they offer the multiplicity and wealth of expression. Yaman Kalyan certainly fits. The big ones and, say, the seasonal ragas are ingrained in the Indian cultural psyche and they go deep. He went to deep places in Yaman Kalyan, too. Listening to him play the opening alap movement was to banish hypertension better than a medicine cabinet of little white pills.

Half an hour in, he paused to talk to the audience, first in Hindi and then English. He invited us to walk with him among the stars. With both tabla players joining in, the pace picked up. Zuheb Ahmed Khan played the first solo almost immediately. Shujaat Khan played lehra. It sort of reverses the normal order. The melodist supports the rhythmist with a steady, cyclical melodic phrase which also acts as timekeeper. It also means the melodist acts as a kind of conductor. And then it was Shariq Mustafa’s turn, again with the sitarya playing lehra. Like his father, Shujaat Khan is renowned for singing in concert as well. He has gone to the next stage, further than his father-teacher ever did in that respect. His discography, for instance, includes his one-off joint album project, Naina Lagaike with Asha Bhosle. Although she is beyond famous for her playback singing in the Hindi and other regional film industries, Ashaji, who turned 92 two days after the London concert, is also the gandabandan shagird (‘disciple’) of the sarod virtuoso Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. (Gandabandan means they had undergone the symbolic thread-tying ritual that binds disciple to teacher.) The first set ended with fireworks with Shujaat Khan playing faster than humanly possible.

And then, since there was no announcement and audiences like to know, came the confusion of the is it?/isn’t it? intermission. The three musicians stayed on stage. He invited the audience to stretch their legs and do whatever people do in the break. Occasionally he engaged in good-natured banter with members of the audience. Time up, the ones who’d gone off trickled back…causing disruption in our neck of the woods.

The second set featured a song repertoire from living and dead, known and unknown authors. Singing and accompanying himself on sitar, the first was from the song-poet. Krishan Behari Noor (1926–2003). (The exact song is easily searched on YouTube; it’s the one with, as I write, 8.4 million views. '…So,' he tells me the next day, 'people are dying to listen to that. I do that…three or four couplets.') The second hit the audience’s funny bone. People burst out laughing at lines. It was a modern song by the Urdu-language poetess, Shabeena Adeed, born in 1974. It reminded me of audiences responding to Bade Ghulam Ali Khan taking on female roles in thumri (a form of light classical music). 'The first two stanzas talk about new love,' he says, 'and how you feel at that time. And it’s something that strikes a chord with everyone who understands it. And the second two stanzas are about how women are treated, or thought of [from a male perspective] […] and what they feel. So that’s why it becomes very personal.' It resonated. It concluded with instrumental masterclasses in sitar breaks and break-outs. The encore was a praise song by an anonymous author about the Islamic mystic and sant, Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti – also called Khwaja Ghareeb Nawaz. His dargah (shrine) and resting place in the Rajasthani city of Ajmer remains a multi-faith place of pilgrimage: a much-needed reminder given modern India’s worryingly divisive politics. At 21:23 the house lights flickered almost unperceptively and, right on cue, seconds later he finished. The Legacy of the Maestros™ series had its auspicious start.

The Britten Theatre is a venue within the Royal College of Music (RCM) building on Prince Consort Road in South Kensington. The 390-odd seater auditorium is laid out as an opera house to an Italianate model with a Proscenium arch. It has a main seated area and three horseshoe terraces. The acoustics must have been fine for ‘downstairs’ (fifty-five quid plus booking fee) or for opera or operetta performances. Even with a voice microphone, up in the upper horseshoes, parts of his spoken introductions and explanations dropped out as offerings to the gremlins of acoustics. And with them, presumably some of the musical nuances. At forty-five quid (plus booking fee) for a cheap seat in the gods, that’s a caveat emptor for concert-goers and a plea for the RCM to review its pricing policy for seats in the sky, especially for chamber music concerts.

In the Eighties I was a greenhorn critic beginning to get Indian concert review commissions. In 1986 Jay Visvadeva presented the sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan (1940–2011) in a long-ago RCM concert hall. The bowed sarangi is a squat, ugly ogre of an instrument that only a mother could love but with a voice that could enchant angels. The audience was predominantly Indian and Pakistani rasikas (connoisseur aficionados) schooled in the old concert ways. I was one of few white faces you could count on one hand. Maybe two others were violin students. He performed Jhinjhoti. Felicitous meends (glides or glissandos) and unexpected twists were greeted with approving head-shakes, raised hands and spontaneous choruses of wa-wa. Since recitals were conversations between stage and audience some murmured spoken responses. Excerpts from my Folk Roots review was used years later in the commercial release of the concert. In the Britten Theatre I had cause to reflect on how concert etiquette has changed in our whoosh-whoosh-whoosh world of mobile phone and social media distractions. I saw the faces of long-dead rasikas Sufi-whirling in their graves.

Shujaat Husain Khan is a musician who restores faith in the traditional arts. Like Sultan Khan in 1986, Khan hadn’t been doing a concert in the Britten Theatre: he had been in the transportation business. He was transporting minds. Not even, as the advert used to say, probably the best… Shujaat Husain Khan was the best sitar player on earth that evening. End of.

With special thanks to Gilda Sebastian, Paul Coombes, Simon Broughton and Santosh Dass.