Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer

Shane Shambhu / Altered Skin, Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer

The Place, 29 September 2018

Bharatanatyam performer Shane Shambhu’s Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer is part dramatic theatre, part one-man comedy, and part classical dance exposition with a postmodern twist. The comedy confessional mode is one we’re increasingly used to in contemporary theatre; Shambhu’s show blends this fourth-wall breaking contemporary mode with classical Indian dance to create an entertaining and thought-provoking new combination.

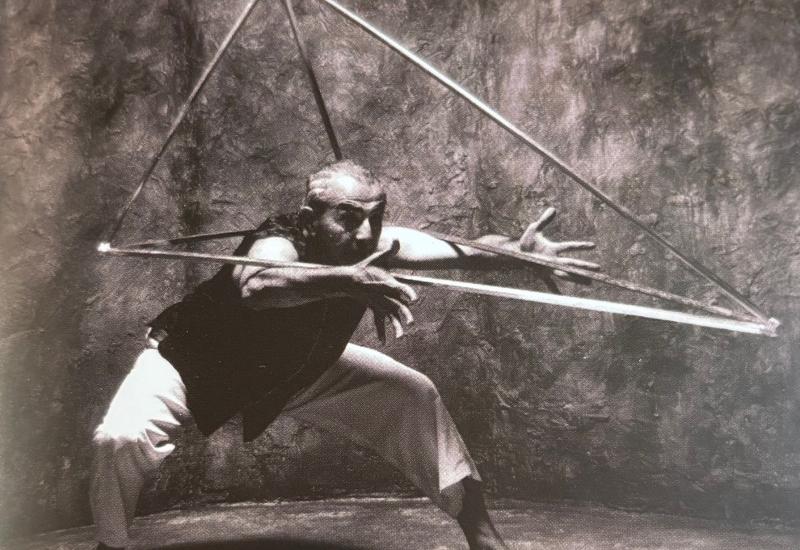

We arrive in the theatre to find Shambhu dancing with himself – a projected video of his bharatanatyam arangetram from twenty-four years ago plays on a screen above the stage, and the present-day Shambhu marks through the steps as if trying to remember the decades-old choreography. The video version of Shambhu is dressed in the manner we would expect of a classical Indian dance performer: bare chest, pleated pajamas, temple jewellery and heavy eye makeup. Present-day Shambhu is dressed simply in white shirt and brown trousers without makeup, jewellery or ankle bells. This pared-down presentation of the classical artform is something Shambhu will later comment on explicitly in his spoken script.

With humorous narration and the repeated promise of a live re-enactment of the arangetram performance seen on video, Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer takes us on a danced and spoken-word journey through a life in classical dance. We hear how Shambhu first began dancing – sent to classes by Keralan parents who wanted to improve the health of their 'really, really, really fat kid'. We learn about the quiet dedication that even an early dance career demands – practising in secret behind a wall in the school playground, working on combinations of steps despite a fear of being mocked by friends. We learn how Shambhu became 'Shampoo', the curly-haired and frequently mispronounced superhero of South Indian classical dance in the UK. And we learn, a little heartbreakingly, about clashes with the same parents who sent Shambhu to his lessons but who expected the young man to move on to a career in engineering or medicine rather than the performing arts.

A warm and engaging perfomer, Shambhu isn’t afraid to layer his performance with reference and self-reference. While posing (hips slanted to the side and invisible hair plaited) as a bharatanatyam performer giving a lecture-demonstration, Shambhu both performs this role in an ironic, highly-mannered style with wink and accent, and performs the role for real, giving an overview of Indian classical dance conventions to those in the audience to those who may not know them. Speaking in the character of himself (or a similarly conscious, constructed version of thereof), Shambhu discusses his own performance style – stripped-back, without bells or colourful silk costumes – while apparently on the phone to a theatre programmer whom he invites to come and see his performance 'tonight, at The Place'. Moments of reflexivity such as these point up the use of personal history as stage material and the self as a scripted character, as constructed as they are authentic.

There’s a repeated mimed motif of carrying a burden (the weight of cultural history, or of parental expectations?) that registers clearly in the viewer’s mind without ever being explicitly defined in the script. Towards the end, as Shambhu finally begins the long-trailed re-enactment of his first professional stage performance, flashes of anger and frustration creep above the humorous surface for the first time. It’s clear from the prior narrative where these have come from – the double-bind of finding one’s place as a child of migrants performing a classical cultural form ('British Asian Dance – or BAD' as one of Shambhu’s revered dance gurus puts it); and of working in a classical form in a contemporary theatrical context, wanting to forge a new style but coming up once or twice too many against bell-and-pajama-based expectations. Shambhu’s primal yelp of anguish from the stage floor as he wrestles an afro wig, a symbol of his own younger self, is genuinely shocking and briefly overthrows the comedic thrust of the rest of the show.

Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer carries its complex social-political and theatrical irony lightly, resulting in a highly entertaining show that asks some deep and resonant questions about the place of South Asian culture in contemporary British society. Shambhu is a wonderfully warm guide through the minefield of his own dance journey; and it’s not every day you get to see a grown man wrestle a wig on stage. Catch it if you can.