Cunningham

Cunningham

Directed by Alla Kovgan

Pulse Dance Audience Club

This documentary on the American choreographer Merce Cunningham was released in cinemas on 13 March 2020. However, the shutters very soon came down. Since it was available to purchase and watch at home we took the opportunity to meet on Zoom and share our responses. Thank you to all who contributed to the discussion.

‘To what end, this eternal daily struggle? Because inside of all that is an ecstasy.’

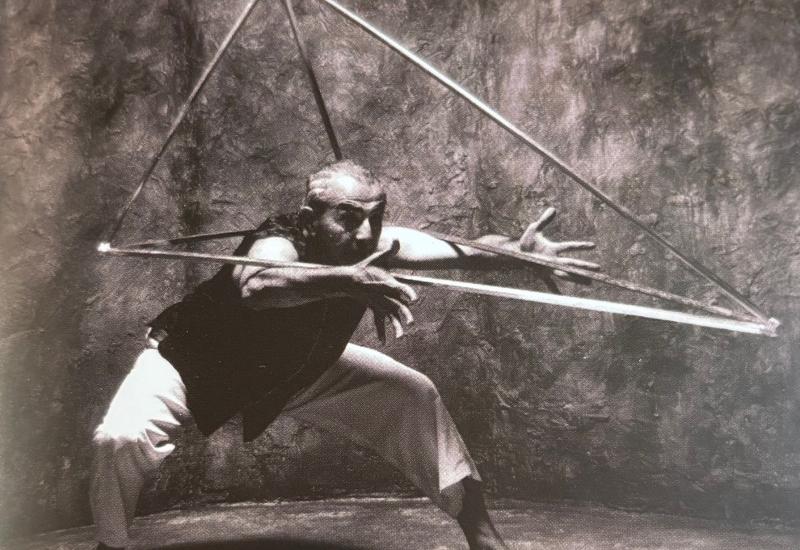

The documentary delivered what, according to the programme notes accompanying his company’s performance in Calcutta (as part of his world tour in 1964), would be ‘a feast for the eyes’. The material lent itself to film. Recreated versions of his works, making the most of sites, spaces and colour, from forest to rooftops to ballrooms, were used alongside grainy archival footage and interviews, writings and animated drawings by Cunningham. Even on our relatively small screens at home, it was ‘exciting, immersive’, a ‘beautiful, natural pairing of film and dance… Film is a much more perfect version of what we’re trying to do on stage… it is about lines and geometry… as good as watching it in a theatre’.

Many members of the audience in this discussion hadn’t been familiar with Cunningham’s work, and found the film a learning experience. ‘It says to me that this is the foundation of contemporary dance’. It was satisfying to be able to trace this in his innovations and those around him. We learnt about the ‘ballet legs’ and modern dance body. When they had tried it, dancers in our audience trained in other disciplines found it very difficult to try to do what his dancers were doing, with their specific technique, which ‘in hindsight, seems very classical’. He talked about ‘making bodies flexible… and allow for as many movement possibilities as I could see’.

In his thought about dance and movement and expressivity, he was rebelling against the narrative structures that Martha Graham, with whom he had been working, was using: he saw the expression in the movement itself, in the technique – which could make it seem impersonal. At one level, we enjoyed simply the exploration of the quality of the movement itself, his spine and length of neck. ‘You can just enjoy watching the body, the whoosh.’ The dancing, without music at first, but with a stopwatch, was highly controlled and disciplined (he had been trained in ballroom and tap); without music one could hear the creaking floors, the natural sounds of jumping and breathing. One audience member commented on ‘how much effort it takes to get one’s mind in that space to execute what you need to without music. Indian classical dance relies so much on music, but they were so intensely focused, they had to create that zone themselves.’

It was not just the intense self-discipline that came across – he was ‘a total machine’ – rehearsing at first in a tiny space, on a cold floor; it reminded us that it takes ‘an overwhelming sense of self-belief’ in the face of having rotten tomatoes thrown at one (he wished that they had been apples, so that he could have eaten them, he was so hungry).

The film reflected the diversity of his work and the movement from more to less abstract. ‘It doesn’t refer, it is what it is, that whole visual experience’, he said. Yet ‘Winterbranch’ was a dark and powerful piece, about violence, which called up race riots, the atomic bomb and concentration camps. Stacey Prickett told us of her experience of going to see a performance in Berkeley after a series of cancellations because of the statewide protests that turned violent following the Rodney King trial in Los Angeles (four police officers had beaten up a black man but been acquitted). She had to go through a police cordon to get to it. It was a most powerful show, with so much political resonance – she felt the piece was about race and tension, because that was what she had in her mind. The emotion was in the movement itself.

There seemed to be a contradiction between the apparent impersonality and the statement that ‘we are a group of human beings’. ‘The dancers looked miserable a lot of the time’, but though ‘he doesn’t show love, you get a sense of love’. ‘Watching it closely one sees a lot of personal interaction. One needs to let one’s expectations drop away.’

Cunningham came across as a thinker and artist, but also one very much of his time, with ‘the other broke artists in NYC’. Boundaries between the arts were more porous, with the composer, the dancer and the visual artist working together: John Cage; Robert Rauschenberg; then later, Andy Warhol (with his delightful silver pillows). Lighting and costume were almost equally important, as we saw from the film, with the last, wonderful, kaleidoscopic piece, with its patterns, colours and play of darkness and light. We can look forward to being able to see it in the cinema, in 3D.