Flexible Bodies, British South Asian Dancers in an age of Neo-Liberalism

Flexible Bodies, British South Asian Dancers in an age of Neo-Liberalism.

Anusha Kedhar

Oxford University Press, 2020.

Reviewed by Magdalen Gorringe

As dancers, busy with class and riyaaz or with (in pre-pandemic days) creating work, applying for funding, tour bookings and rehearsal, the weary business of our country’s government can feel very distant from our day to day lives as artists. The fragility of this distance is being forced upon us now, as British artists will be required, post Brexit, to apply for separate visas, separate work permits and separate customs waivers for each individual state in the EU they hope to tour. So much for Brexit being anti bureaucracy and red tape – thanks for the paperwork Boris and Nige! Still, should any artist remain in any doubt of the intimate connection between their creativity and the wider political context in which they live and work, Anusha Kedhar’s award winning book Flexible Bodies (2020) will swiftly put their illusions to rest.

Situating ‘the late twentieth-century emergence of British South Asian dance as a genre in relation to the parallel rise of neoliberalism and multiculturalism in Britain’ (1), Kedhar explores and challenges the ‘presumed naturalness and expectation of dancers’ flexibility (2), which includes, particularly for South Asian dancers in Britain ‘the flexibility to perform both South Asianness and Britishness, to be simultaneously exotic and legible, particular and universal, different and accessible, other and not other’ (3). Taking as her starting point five keywords ‘closely associated with neoliberal and multicultural ideologies: innovation, assimilation, mobility, risk, and value’, Kedhar devotes a chapter of her book to each key word, ‘elucidating the relationship between a macro theoretical framework and the micro corporeal movements of the dancing body’ (28). It is this constant cross referencing between micro and macro, between the public and the private, the proclaimed and the intimate, the twist of a hand in an alapadma and the bitter twist of a new immigration regulation that makes Kedhar’s book so insightful and compelling – and ultimately so necessary for us as dancers to read, both as a means of self-understanding and of empowerment.

The first chapter, ‘Innovation’, reflects on Kedhar’s experience working as a dancer in Mayuri Boonham and Subathra Subramaniam’s company, Angika. Against the backdrop of a policy demand for the ‘innovative’, ‘almost always’ understood within the South Asian dance sector as demanding ‘an engagement with Western dance techniques, aesthetics, choreographic approaches, and / or performance practices’(33), Kedhar traces how Angika charted a course that worked ‘strictly within the bharatanatyam form’ but engaged with ‘unconventional choreographic, production, and staging choices’ (35) thereby finding that elusive point between being ‘different but not too different’ that, she argues, enabled their success. For Kedhar, not only in the case of Angika, but more widely, ‘it is this flexibility to balance diversity and innovation that characterizes the aesthetics of British South Asian dance’ (34). The success of this dance genre raises a troubling question about the nature of the supposed ‘ideal British Asian citizen’, who, she suggests, like British South Asian dance, is ‘adequately other but not excessively foreign’ able to ‘be integrated within British society but still …contained within the ethnic/ minority box’ (43).

If Chapter 1 raises the image of the ‘model minority’, Chapter 2 starts with its anathema - the spectre of the ‘inflexible, anti- capitalist, unassimilable terrorist’ (78) and the bombings of 7/7. This chapter centres around the keyword ‘assimilation', and builds on a close reading of four dance works – Akram Khan’s zero degrees (2005) and Abide with Me (2012), Shobana Jeyasingh’s Faultline (2007) and Nina Rajarani’s Quick (2006). Each piece, Kedhar argues, presents an interpretation of young, brown masculinity that runs counter to the narrative of ‘the brown male body as the "enemy within", effectively unassimilable into Western culture and society’ (114) that dominated after 7/7 and that led to the increase of ‘moral panics, paranoia, surveillance, practices of deprivation, and stop-and-search’ (114). Khan moves fluidly between kathak and contemporary dance (zero degrees) and evokes a softer, nurturing masculinity (Abide with Me). Jeyasingh’s Faultline calls attention to the audiences ‘own complicity in stereotyping brown men’ (115), while the ‘intense speed and agility’ of Rajarani’s dancing city traders in Quick ‘aligned the brown male body with neoliberal values of speed, flow, and productivity’ (115). In this way the on-stage performances of the brown male body disrupted the off stage perception of the brown male body as a violent threat.

Chapter 3, focused on ‘Mobility’, pays tribute to the ‘flexible labour of transnational South Asian dancers who helped produce the signature aesthetics of a distinctly British contemporary dance genre’ (118). While these transnational dancers demonstrated their ‘versatility’, their ‘agility’ and their ‘adaptability’, British immigration policies since 2008 have become ever more ‘immobile’, ‘inflexible’ and torturous – resulting in a situation whereby it has only been the most high profile and highly funded dance companies that have had the personnel and resource to overcome the necessary bureaucracy to hire non-British dancers. As a result, Kedhar argues, ‘today, British South Asian dance has become whiter in both the composition of its dancers and its movement lexicon’ (137). ‘Immigration and arts funding policies’ viewed as ‘choreographic tools of the state’ shaping ‘where and when migrant dancing bodies move’ have had a visible impact on the British dance landscape leading to the ‘general dilution of South Asian dance aesthetics within British South Asian dance companies’ (137).

Chapter 4, on ‘Risk’ brings to the forefront a subject too often neglected in studies of dance and dancers – injury and pain. Situating the demand for ever greater risk taking within dance against the ‘risk seeking’ ideology of neoliberalism, Kedhar argues that the need for South Asian dancers to make their work ‘legible’ for an audience unfamiliar with South Asian dance can often mean ‘displaying greater physical risks, technical virtuosity, spectacular choreography, as well as ethnic particularity and cultural authenticity’ (144). In this way, for ‘British South Asian dancers, pain and injury are induced not just through neoliberal working conditions in the studio but also through multicultural expectations for assimilation and legibility outside of it’ (145). Yet despite the pressures placed on them and the physical pain and economic precarity that they endure, British South Asian dancers nevertheless find a way to subvert the risks demanded of them to protect themselves and their colleagues and to carve out a space for elective (and hence pleasurable) rather than coerced risk.

The final chapter, which considers ‘Value’, explores Kamala Devam and Seeta Patel’s award-winning film, The Art of Defining Me (2013), a film that through sarcasm and humour exposes how (contrary to the film’s title), ‘The art of defining oneself is often in the hands of others who want to box you into familiar categories’ (197). Such familiar categories serve South Asian dancers both positively, to highlight their existence and negatively, by boxing them in to expectations, so that if for (the white) Kamala, ‘Indianness is an identity that must be put on’, for (the brown) Seeta, ‘it is an identity that can never be taken off’ (197). Nevertheless, the film is in itself, Kedhar argues, a testament to the creative power of artists to reclaim and redefine themselves, even as its take home message is one of systemic inequity - ‘Multiculturalism celebrates difference while the structural racism that underpins it and the colonial foundations of those who control resources and capital goes unchecked.’ (198)

Kedhar ends with a sober note, her epilogue recognising the anti-immigrant rhetoric that fuelled Brexit and the reality that ’a global pandemic that will most certainly be used to justify a further entrenchment of nativist and neoliberal agendas’ (202). Reflecting on Shane Shambhu’s Confessions of a Cockney Temple Dancer, his humorous and creative refusal of the boxes placed on him by so many – parents, audience, programmers, state – cannot in the end protect him from the visceral pain of having to constantly fight just to be – himself. Shambhu’s flexibility comes at a cost and, Kedhar asks, ‘as we teeter on the precipice of environmental catastrophe, we must also ask what will be the cost of increasing neoliberal flexibility on the planet and its resources? Who and what will be stretched to their limits, and who and what will reach their breaking point?’ (202).

Cogently argued, clearly written in elegant jargon-free prose that embraces the intimacy of two dancers chatting in the kitchen at the same time as it explodes the meritocratic myth of neo-liberalism, Kedhar’s book does not suggest that life will be any more flexible or accommodating for the flexible bodies of British South Asian dancers. Yet, in its detail and analysis, it points a way for us to make our flexibility work for ourselves – and to dance our way around, through and out of the boxes that seek to hold us.

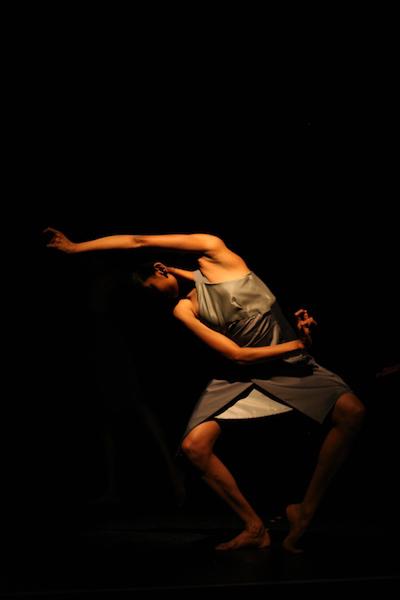

Image: Hema Sundari Vellaluru in Cypher (2008). Choreographed by Mayuri Boonham and Subathra Subramaniam. Performed by Angika Dance Company. Photographed by Nigel Boonham.