Dance and Society: Beauty and the myth of the ‘real’ bharatanatyam

Image: Simon Richardson

Dance and Society

In the third of our articles in this series, Sammitha Sreevathsa raises the question of who defines our ideas of beauty.

GROWING UP AS A DANCE STUDENT, to look 'beautiful' was not a desire I had for myself as much as it was a desire I had for my dance teacher. This desire for my dance teacher to appear a particular way, I realise today, had a direct link with how I feared she would be perceived by the mainstream classical dance community.

In my second phase as a dance student, I found myself learning bharatanatyam from a lower caste, Malayali Christian teacher. She walked into every class with her daughter, with her dark skin, curly hair, synthetic salwar-kameez, a gold chain, but without a bindi. So incongruent was she with the dominant idea of fair-skinned Hindu 'beauty' of classical dance that this incongruence took the shape of a dull, permanent, deep-seated fear in my teenage body that I was perhaps not learning dance from a 'real' dancer. I feared that the skills I was acquiring from her were not authentic and, by extension, the dancing expressions of my body were inauthentic too. On the rare occasions when she came in a saree, bindi and jasmine flowers, I would dance well, relieved that at least temporarily, no one would ask why I had chosen to learn bharatanatyam from someone called 'Maria Joseph' (name changed). 'Why couldn’t she look pretty every day? When it’s actually so easy!' I wondered.

No one actually questioned me, but in case they were going to, I had my answer ready: ‘She is just a stop-gap teacher. I will learn from a “real” dancer soon when I grow up.' I was afraid the field would perceive me the way they perceived her – not a real dancer. I was desperate to grow out of this dance class, convinced that I was meant for a better place, a famous dance teacher who would look the part she played. Whose name could finally legitimise my dancing abilities. My araimandi would look more bharatanatyam if I could do it in a dance class where all the girls wore half sarees.

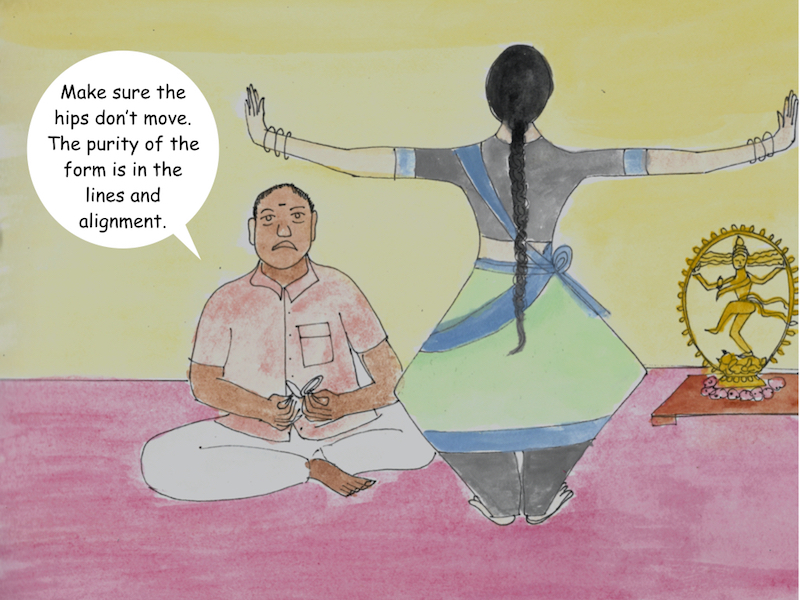

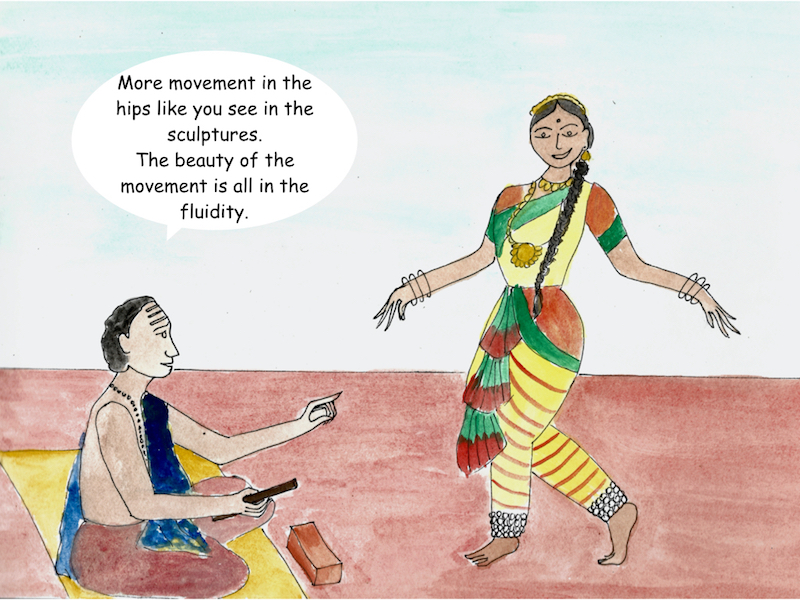

Artwork by Veena Basavarajaiah

In 2008, when I moved to Bangalore, my hometown for my undergrad, I was determined to find that one great teacher who would take me under her wings, in whose authoritative gaze I could bask and whose social capital I could inherit. I finally found myself standing in just the kind of place I always wanted to be in. In front of me sat a teacher with a diamond nose stud in a cotton saree, with a big bronze Nataraja gracing her drawing room. No more suffering bad Sanskrit pronunciation, I thought. The décor in her drawing room had the power of making me feel like I truly had arrived. But to my utter confusion my body vehemently protested this new training. I was eighteen when 'DO NOT MOVE YOUR HIPS!', was hurled at me the first time. This is when it occurred to be that in my desperation to disown my previous teacher, I had overlooked that her knowledge had percolated too deeply in my body – blood, bones, heart, and few years later, into my intellect. It simply couldn’t be covered in the garb of a half saree and a bindi.

Recently my friend and a kathak dancer, Mridula Rao, shared what she was told in a kathak workshop by a famous guru . 'We keep our hips absolutely still when we do na-dhin-dhin-na, else you know what it will start looking like? You are not a naachnewaali (‘dancing girl’).' Mridula recalls that 'this guru loved thumris and had learnt and passed on many of Bindaddin Maharaj’s compositions to her students. Thumak-ri! – the word thumri comes from thumakana (‘to walk with swaying hips’). But where is the thumak happening in the body, is it not the hips?' Her question was compelling and triggered the realisation that the politics of the classical aesthetic includes the ‘form' itself, and dancing women’s hips have been the field on which the politics of respectability, caste and patriarchy have played out over the decades.

I remember that my dance teacher’s hips gyrated freely when she did all the footwork along with us while teaching and it is only today I am able to make sense of her dancing body with a gaze that is not borrowed. In all likelihood, she would never find a place in the starry constellation of classical dancers. But her dancing body was knowingly or unknowingly a protesting body, a rupture in the lofty parameters of what can be called authentic and aesthetic: a Christian body, teaching bharatanatyam in a public hall attached to the local Ganpathi temple. Perhaps this reality was made possible because it was an obscure locality in Navi Mumbai and not Chennai or Bangalore. Dance in her class was not a matter of reverence. She wouldn’t hesitate to include a few bollywood choreographies for the 'annual-day' repertoire if she saw an audience for it. Dance for her was not above sustenance.

Today I find myself yearning for the pleasure I was allowed as a child in her dance classes – the freedom to move my hips, the freedom to foreground my own preferences of taste and style, a teacher who was unashamed to admit that she doesn’t know (it was Hindu mythology in her case), a space where I did not have to worship dance to be a good dancer.

'Aesthetic' (as opposed to anaesthetic) is made up of stuff which stimulates our senses – touch, sight, sounds, smells, taste. What we’re disgusted by and what is palatable to our senses is deeply determined by our social locations. Classical dance was refashioned to make it palatable to the dominant social groups in India – in its body, poetry, costume and emotional flavour. So dominant are these aesthetic sensibilities and the desire to keep them 'pure', that anyone who doesn’t perform these can be rendered 'unreal', 'illegitimate', despite all evidence of their existence. My teacher stands as a tall example of the subversions that are made possible when a dominant form interacts with marginalised bodies.

Veena Basavarajaiah is a movement artist from Bangalore. She uses her illustrations to address issues of the art world through her insta profile cartoon_natyam.