From Below the Ivory Tower

Dance and Society

Pulse has commissioned this new series with the dance student in mind.

‘…truly critical deliberations on culture in India… are virtually non-existent.’

(Davesh Soneji, interviewed by Sammita Sreevathsa for Firstpost. Full article here)

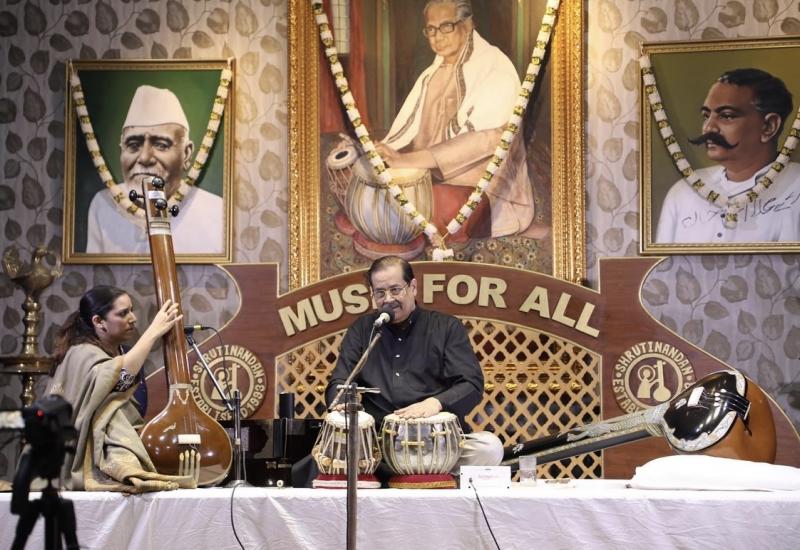

The society in which we live and the dance we practise are closely connected. 'Dance and Society' aims to look at classical dance through the lens of class, caste, gender, religion and politics: where and from whom do we learn dance; what do we dance about? How do the dance items resonate with our lives? The more we interrogate our dance forms and practice, the more convincing and powerful we will be as communicators.

We would like this to be a space where students and teachers can debate these issues. Let’s take a plunge into unchartered waters with the first of this series…

– Editor

Years ago, I watched a bharatanatyam performance by a group of girls in Bangalore who were dancing to a popular shabdam [a dance item with both nritta and abhinaya, rhythm and expressive dance] called ‘Sarasijakshulu’. The performance depicted a young Krishna’s flirtatious escapades as he secretly spied on women bathing in the Yamuna river through the foliage of a blooming tree, after he had stolen all their clothes. The situation grew more intense when he refused to return their clothes despite their pleadings. As the performance reached its climax, the main heroine, unable to control her anger, rose up to confront him. Just as she was about to raise her voice, she realised that she had exposed herself to Krishna – thus melting her anger into what is called sringara rasa [love].

As the auditorium burst into applause, I left the place in a great huff, angry with myself for indulging in this voyeuristic exercise. Shouldn’t this be considered harassment? Why should this be okay just because the man is a god? Why do we not hold classical dance to the same ethical standards to which we hold everything else?

A couple of years later, a friend who is a kathak dancer was sharing her experience of teaching a similar choreography to her teenage students. I was thrown off-guard when she told me that all her young students loved dancing to this Krishna-Gopika story, and they truly enjoyed performing the battle with Krishna as a flirtatious banter. Perhaps it is the only way their sexual desires find some means of expression? In a society where it is deemed immoral for young girls to express their sexuality, where their lives are controlled by social codes of patriarchy (how to dress, where they are allowed to go, who they can meet, how long they can stay out of the house), dancing this story probably becomes not just a fun but a liberating experience. Was I too quick to judge the performance that I saw on stage the first time?

Although the above instances seem like contrasting interpretations of what it means to perform the same story, they both stem from the social experiences and anxieties of being a woman in a patriarchal society. How we experience classical dance as a performer, teacher, audience or a student is deeply coloured by who we are in that society – by race, gender, class and (certainly in India), caste.

I grew up as a student of bharatanatyam and as a student of Humanities, but it was not until I started writing and teaching about dance that I began drawing connections between the two. During one of my classes, a student recounted her experience of learning bharatanatyam as a child. ‘Every year when we would get closer to the annual performance, the atmosphere in the dance class would become tense and competitive. My teacher would charge a different fee for different choreographies. Those who could pay more could learn more complex choreographies- and these kids would receive compliments not for being rich but for being great dancers!’

Our participation in such experiences of inclusion, exclusion and prejudice, both as victims and as perpetrators constitute the huge underbelly of the field of classical dance. It shapes our attitude towards our practice and determines what kind of dancers we go on to become. Yet these aspects remain largely unarticulated in the popular writings on dance.

Through this column I hope to see what kind of explorations could be made possible by asking questions of history, sociology, economics, anthropology, politics and philosophy in the field of classical dance. Can bringing dance and humanities together help us make a little more sense of our lives as dancers in this society?

If you have thoughts, questions or experiences you would like to share, you are welcome to write to me at sammitha.sreevatsa@gmail.com

Sammitha Sreevathsa is a dance writer and educator based in Bangalore.