Aakash Odedra and Hu Shenyuan In Conversation

Samsara : A major new international collaboration

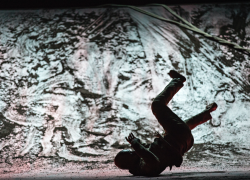

This year will see the pairing of two extremely virtuosic dancer-choreographers in a new dance production that reinterprets a classical Chinese epic. Hu Shenyuan and Aakash Odedra première Samsara in Melbourne, in March 2020. Shivaangee Agrawal went to speak to the two artists and watch them rehearse.

How did you both decide to work together?

Aakash: I was watching Yang Liping’s Under Siege. When Hu came onstage, there was no acrobatics, no extravaganza. His movements were so fluid, I couldn’t tell where his leg stopped and his head started - his limbs were like mercury, beyond water. There was a silence in the auditorium that had the energy of a tornado - it was as if everybody there was in sync with Hu. I wanted to dance with him.

Hu, you’ve joined forces with Aakash through a shared interest in the choreographic concept. The basis for the work is ‘Journey To The West’, a hugely important classical text in Chinese literature - could you tell me about your relationship to this story?

Hu: When I first heard Aakash wanted to create a production based on 'Journey to The West', I was very confused, it’s a very famous work that lots of people have interpreted - I was afraid we would repeat what others have done. But when we started working, we decided upon an interpretation that’s more religious and spiritual than most - we decided to focus on the concept of Samsara.

Though popularly understood as ‘reincarnation’, Samsara is actually an esoteric concept - surely the complexity in such a philosophically rooted topic is endless. How do you go about simplifying the philosophy for the purposes of choreography?

Hu: We are incorporating the concept of Samsara into the way we are actually making the work. There’s a persistence, repetition and reincarnation in our choreographic process itself. The Chinese translation of this work is called ‘a road without a road’ and I think it’s how we are thinking about it. When we do something and we don’t know where we are going or where the path is, we try to carve our own path. When we look at our destination from afar, no road appears. But when we start approaching, a road naturally appears in front of your eyes. When we were choreographing this production, we didn't know exactly what we were going to do, and it was on the way to the core of this work that we found out what we wanted to present.

This is one of the most famous works of Chinese literature that deals with Buddhism, how closely have you stuck to the text of Journey To The West?

Aakash: We haven’t stuck too closely to it. It’s an epic tale, we have focused on what’s important to us. In the story of this pilgrimage, it took the monk 14 years to make the pilgrimage. But before him, there were 54 other monks who attempted the journey and didn’t make it. For me, it seems to be the same monk born again and again and again; each time it’s like he’s leaving some part of cellular body behind. There’s something very significant there - a parallel between him and us making our spiritual journey upwards. Hu and I both left home at 15, both didn’t know what we were going to do. We both came to starkly different places to where we’d grown up - Hu came to Beijing, I found myself in Mumbai - and a new chapter of our lives began. There was something driving him and driving me. All these journeys happen in parallel, and at one point, they encounter each other, but then they part again and continue beyond. This work is also about cultural codependency. The irony is that in an era today when travelling and making journeys is so easy, the actual barriers to connection are getting stronger.

You’re both working with classical forms. Hu, could you tell us a little bit about the Chinese movement styles that you work with?

Hu: Breath rhythms and circularity are paid a lot of attention in Chinese classical dance, along with triangles. The circular body is generated around the rhythm of breath. I used to dance a lot of Chinese classical dance, but I haven't done it since I was 21. I don’t intend to particularly use this practice, but this is intuitive to my own vocabulary, and so will have naturally found its way into this piece.

I’m really curious about the collaboration here on artistic terms. As very active and established artists, you must both have strong aesthetic preferences and signatures. Who makes the choreographic decisions, and if both of you, then how exactly do you share it?

Hu: Aakash gives ideas and structures which we respond to. We make decisions together; if we agree we don’t talk about it too much. There’s a tacit understanding. When we disagree, we communicate and combine to create a new idea. When there are disagreements, there are actually more possibilities.

Aakash: I feel like we are two bodies, one soul. It’s really strange, but our tastes are almost the same. I almost understand him when he’s speaking Chinese - language doesn’t become a barrier with us. The first time that we danced together, it was as if we knew each other from the past. You might say, a sense of Samsara!

But there is a language barrier! What’s it like working with a translator in the room?

Aakash: There’s a synergy in the room. Translation is happening on three different levels - Hu and I are communicating but the interpreter is also communicating with each of us. Historically, language was not so much of a barrier - we expressed with the body and with gesture - which we have sort of lost. In this project, we have a chance to understand each other through our bodies and without words - for me that’s what dance is.

You’re going to be performing this to primarily white audiences in Melbourne, who will see two Asian artists doing a work about Indian and Chinese spirituality. How do you avoid this all becoming very exoticised?

Aakash: Let’s talk about incarnation. Throughout history, our traditions have been ‘cleansed’ to make it more relatable for people. The devadasis and their sadir-attam had to be ‘purified’ for it to become what Bharatanatyam is today. Every time we try and stay away from some aspect of our form, we end up doing the same thing again - we are ‘cleansing’ ourselves so that we can be more relatable for people. How people want to interpret the work shouldn’t matter - if you strip away the philosophy of Samsara from the production, you have two people who are moving; if there is emotion, sensitivity, connection, then the work will connect with audiences.

Can you tell me about the creative team behind the production, other than yourself and Hu?

I’m very pedantic when it comes to lights. We are in a world where we are creating cinema on stage, it’s no longer just dance. Creating the set and lighting is like a delicate recipe. The lights are very important and I’m excited about having Yaron Abulafia on lighting design. Then we have Tina Tzoka on set design, K H Lee on our costumes, Lou Cope on the dramaturgy and Nicki Wells composing the music - and performing it live! She’s incorporating live Mongolian throat music - we are really excited about all of these elements creating their own Samsara on stage.

How would you say this project is different or similar to your own work to date?

Hu: For me, it is a production with the least number of performers and the most use of props! It’s also unique for me because of the very long rehearsal period. We’ve been working on this since 2017 and this huge time-frame allows us to really play and try lots of ideas. It sometimes feels like we completely break everything we’ve done on the previous day of rehearsal and start all over.

Aakash: It’s a duet. I’ve spent my whole life doing solos, and though I hated it at first, it became a way of life. I’ve become very used to it, and isolated almost. Working with Hu is very exciting and challenging. He’s incredible...he doesn’t belong on this Earth!

After the world première in Melbourne, Samsara will continue to Shanghai, Birmingham, Leicester, London and Paris. This production has been made possible by the generous support of the Bagri Foundation, a family foundation dedicated to promoting the arts and culture of Asia. Shivaangee gathered some thoughts from Alka Bagri, Trustee of the Bagri Foundation.

As a principal supporter of this new work Samsara, what about this global collaboration is most exciting for you?

Hu and Aakash are truly the finest in their field and we are pleased to be able to share their gifts with new audiences. Samsara is special too for us as it adapts a classical Chinese tale in a new way, reframing the traditional story within a contemporary space, akin to the Bagri Foundation’s own ethos. We are eagerly anticipating seeing the final production!

The Bagri Foundation is a key supporter of Aakash Odedra Company. What to you makes Aakash a stand-out artist in the UK?

Aakash Odedra’s absolute precision and commanding presence hold him above the rest. Despite his small frame, his ability to fill the entire stage was evident when he took part in Ravi Shankar’s Sukanya Opera, supported by the Bagri Foundation in May 2017. I was fixated upon Aakash’s performance and I knew from that moment I had to do a project with such an amazing talent. Rooted in the international Leicester community and headed up by the fantastic producer Anand Bhatt, his company not only tours internationally, but also maintains a successful local learning and participation programme. We are really happy to be a key supporter.