Searching for Srimoti- Tagore's Heroine Today

Vikram Iyengar, kathak dancer, choreographer and curator, is the founder of The Pickle Factory, Calcutta, a hub for the practice, discourse and presentation of dance and movement-based performance. He tells us about the initiative and how the first Prelude Dialogues analyses Rabindranath Tagore’s Natir Puja, written in 1926. Does the dance drama really challenge the status quo of the hereditary dancers of the time? Read on to find out the multiple approaches with which the piece can be understood.

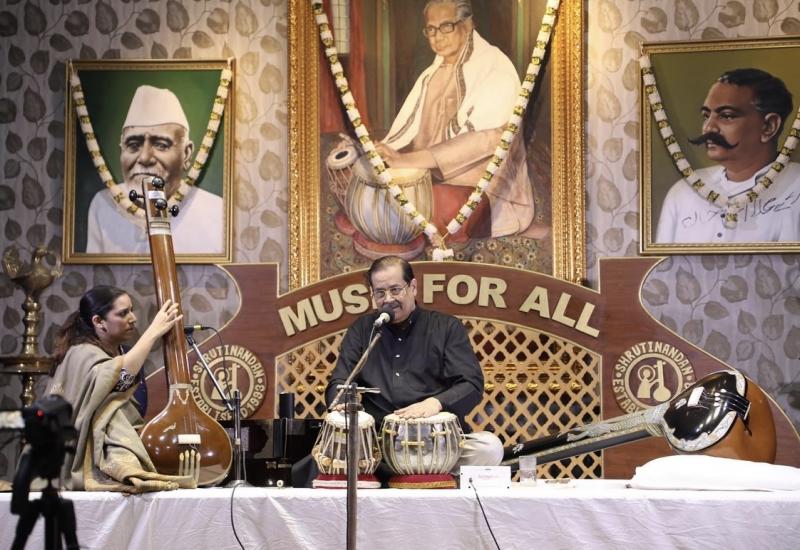

The Pickle Factory Dance Foundation, Calcutta was set up as a response to the absence of spaces for the development for dance in India: spaces where practitioners can explore their practice, share and exchange ideas and values, and interact with current and potential audiences, embracing and cutting across the many frictions of form, style, aesthetics and politics that now divide rather than strengthen us. Our first season in February-March 2018 comprised performances, workshops, dance interventions in public spaces, discussions, an exhibition and more, presented in a variety of venues across the city.

Historically a centre for arts experimentation, Calcutta still enjoys a reputation for being a city of culture. However, for the last few decades, a large proportion of developing performance practice in India has not been seen in the city. Similarly, Calcutta is often not on the itinerary of visiting international work. Add this to the general lack of critical engagement with (as opposed to criticism of) dance work in India, and the city’s audiences offer a strange mix of deep curiosity and shallow experience.

Committed to nurturing an interested, invested, and informed community around dance and movement practice, it is vital for the Pickle Factory to develop a critical vocabulary around practice, and create the space and habit of imaginative discourse open to both offering and meeting challenges. The Pickle Factory Preludes series developed out of this thinking:

How do you read and respond to dance and movement-based performance? How do you create a discursive space that is informed by a sense of history, personal and collective experience, various lenses of viewing and perceiving work? What are the paradigms, histories, philosophies, politics and contexts within which an artist locates his or her practice? And how do we define a pedagogical space that keeps this practice firmly at the centre of discussion, simultaneously drawing from and connecting to a diversity of experience across time, space and fields?

Co-ideated by writer and educator Aveek Sen and dancer-choreographer and arts researcher Vikram Iyengar, it is important to ensure that Preludes attracts a small but diverse audience. The sessions, therefore, need to be playful and provocative, inventive, intuitive and interrogative – much like how artists create their work. Equally, it is imperative to redefine the usual locus of such discussions that seem to always refer to a heavily Eurocentric understanding of the modern and the contemporary. With this thinking and the project being located in Calcutta, it was but natural that the first module developed around the work of Rabindranath Tagore: Tagore, Dance and Modernism.

Our ideas coalesced around a playtext written by Tagore in 1926 – Natir Puja. Tagore wrote this based on his earlier poem Pujarini, itself based on a Buddhist tale about a dancing girl, Srimoti, who goes against the king’s orders and offers evening prayers at the ruins of a stupa that the Hindu king has destroyed. Srimoti is, of course, killed for this action. The poem and the play are vastly different texts. The latter features only women characters and – among various other complex social and power structures – proposes a new theory of dance.

This is the 1920s. The Anti-Nautch Bill – that saw forms like kathak or sadir as objectionable due to their highly erotic content – has been passed. On the other hand, cultural expressions such as dance are being held up as symbols for the national movement, and bowdlerised to fit middle class (and upper caste) palettes. Tagore writes a play with the ‘tainted’ character of the dancing girl as a central character. This is first produced at a semi-private performance featuring only women from the upper Bengali middle class milieu. He offers her a path to salvation through turning her dance into worship, divesting herself of her ornaments, and dying in the process. Such a moment of modernity for the woman, where she redefines traditional norms to indicate a catastrophic moment of transition, is often found in Tagore’s writings. But the woman in question rarely lives this moment out.

This was a central point in the discussions. What was Tagore proposing with his engagement with dance at that time in Shantiniketan? He was on the one hand inviting the upper class educated Bengali ‘bhadrolok’ to send their daughters to him for an all-round education. On the other hand these 'Ashram Kanyas' were taught various traditional dances, and also performed in public during a period when such dance was frowned upon. It was important to note that Natir Puja does not question the prevailing attitudes towards dance and the courtesan. Tagore, too, suggests that the only way forward is sacrificial spirituality, a path where the dancer ceases to be a flesh and blood human being with complex desires, but becomes an abstract symbol. Classical dance in India today – how it is danced, how it is communicated, how it is perceived – continues to suffer from this extreme deification. Looking at films such as The Court Dancer (1944), Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje (1955), and Amrapali (1966) only reiterates this in various ways. It was also interesting to note the Buddhist connection through Srimoti, Amrapali and Prakriti (heroine of Tagore’s Chandalika), all marginalised women ‘saved’ by their renunciation of the world to follow the Buddha.

This first Preludes module also aimed to locate Tagore and this text within an international context. Tagore was well-travelled in Europe, and well aware of the new ideas in art, philosophy, science, psychology and more that underlay a conflicted continent in transition – a conflict that found resonance the world over, including India. The operatic music of Richard Wagner, with its completely fresh and edgy treatment of harmony and tonality, the works of Oscar Wilde and his trials, Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, written in 1920 – Tagore was part of and contributor to this universe of imagination, critique and discovery.

This larger global and cosmopolitan map was brought into the Preludes sessions to illuminate our reading and our response to Natir Puja. Tagore’s Srimoti, Wilde’s Salome, Wagner’s Isolde, Strauss’ Elektra… how does one read this figure of a woman dancing to her death, and read it again – perform it even – from our contemporary perspectives?

Looking at the play in purely historical terms, what kind of dancing and singing would Srimoti perform given who she was in the time the piece is set? It is highly unlikely to have been anything akin to how Rabindrasangeet and Rabindranritya is (has come to be) sung and danced by Bengalis across the world. Applying a different lens of history – that of the date of writing – the singing would have been the more nasal style associated with the bai (courtesan) culture prevalent in cities like Calcutta – a culture, a tradition, a practice, a people then banned, excluded and derided by the Anti-Nautch Bill.

What would she have worn? There are clues given in the text in the last act, where she is described as arriving to dance heavily bejewelled – something that first attracts scorn and contempt, and then shock and awe when she divests herself of her decorations one by one to offer worship through her ‘purified’ body. The text of the lyrics she sings puts this body at the centre of her worship: bondona mor bhongite aj shongite biraje (my worship resides in my dance and in my music). How many subversive interpretations this one line of poetry allows! I am reminded of Tamil actress Kalai Rani’s forceful exit through the audience in her solo piece Varugalamo Ayya that completely demolishes the careful social structure of a bharatnatyam world. And of the astonishing Manipuri actress Sabitri Heisnam in the last scene of Dopdi, where her naked and violated body becomes the weapon and site of protest.

There is little challenge to status quo in a performance of Natir Puja today, while the text itself – especially the last pivotal scene – is as much about sacrifice as it is about challenge and protest. We asked ourselves – if we were to imagine performing this last scene today, how could we raise questions about the physicality of the female body in various social, religious and performative configurations? How could we reclaim the simultaneity of the sensual and spiritual in the character of Srimoti? And how can we imagine the dance as a moment of catastrophe – a moment where the queen, the princesses, the attendants fear for the future of everything, a moment that prevents the king himself from entering this meeting and mixing of the sacred and profane among the ruins of a stupa / the ruins of religion?

We watched the last moments of Pina Bausch’s Le Sacre du Pritemps with these thoughts and questions. This violently beautiful woman in red, tearing herself apart as she dances to extinction in a landscape of ruin surrounded by a crowd of ambiguously voyeuristic observers – is this a possible Srimoti?

Vikram Iyengar is a dancer-choreographer-director, researcher and writer based in Calcutta. He is co-founder of the Kathak-based performance company, Ranan and initiator of The Pickle Factory – a hub for dance and movement practice and discourse. His performance work is linked by a fundamental and continuing engagement with the kathak form and kathak-informed body. An ARThink South Asia Arts Management Fellow (2013-2014) and Global Fellow of the International Society for the Performing Arts (2017), he is one of four Asia Pacific participants in the International Arts Leaders programme run by the Australia Council for the Arts (2017-18). In 2015, Vikram was awarded the Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Akademi in the field of contemporary dance.