Clay, cues and cardboard houses: A day in the double life of a Performer-director

Clay, cues and cardboard houses: A day in the double life of a Performer-director

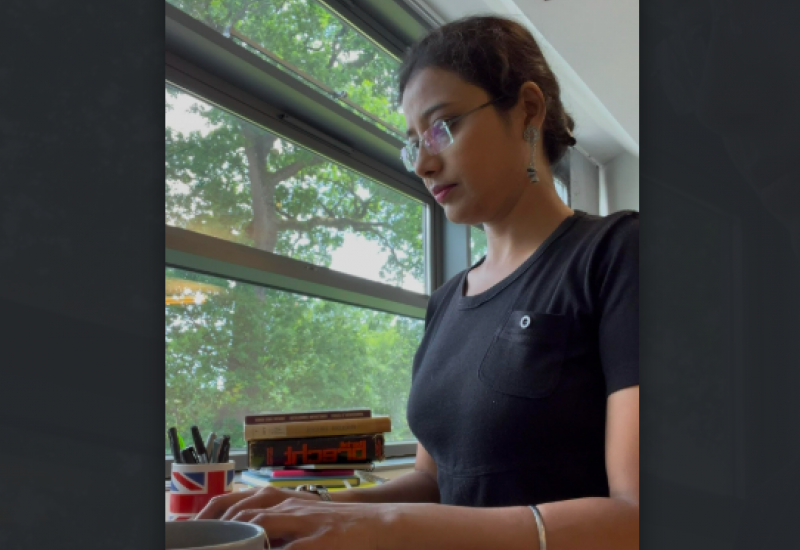

By Vidya Thirunarayan

Artistic Director, Thirunarayan Productions

Photos: Robert Golden

HOLY DIRT premiered at the Ensemble festival, London over the last weekend of July’25.

Creator /performer : Vidya Thirunarayan

Director/Designer: David Glass

Somewhere in the creaky corridors of memory I recall a beloved column from the plastic-wrapped Times magazine of the 90s : A Day in the Life Of. It always featured a celebrity, an author or minor aristocrat who, by 9 a.m., had already meditated, done Pilates, and secured a book deal.

Naturally, I thought: why not me?

So here it is—my humble submission from the trenches—an inside view of what it was like to open my new show Holy Dirt at the Ensemble Festival in London. Spoiler: there was no silk robe, but plenty of damp clay, papier-mâché politics, and a megaphone with a superiority complex.

Let me begin at the beginning—or rather, the week before the beginning.

That week, my house ceased to be a home and became a mildly chaotic artisan sweatshop. I painted megaphones a tasteful shade of industrial melancholy, cut out enough paper dolls to stage a papery revolution, and lovingly prepared clay in three emotional registers: hopeful (firm), distraught (sticky), and existential (gritty). My long-suffering husband and saintly friend DFB who also doubled up as my rehearsal director , under my strict supervision lined miniatures of buses, fridges, and council houses so they wouldn’t unceremoniously collapse mid-performance. Meanwhile, I painted black stones—because symbolism, obviously.

Interspersed with this handmade mayhem, Sasha (co-performer and co-survivor) and I squeezed in three solid days of rehearsal with DFB in a Methodist church hall, where the echo was generous and the spiritual support subliminal.

Saturday, 10:00 am: Arrival (and the joy of getting lost)

I arrived on site precisely 30 minutes early, which is to say: I got lost, as I always do, but factored in enough time to congratulate myself for getting lost efficiently. Professionalism!

Inside, efficient Sam and Glenn were setting up the stage, Foz (composer and sonic alchemist) was entangled in cables at the sound desk, and I was already spiralling through my usual morning-of-the-show mental circus:

- Did I cover the clay with a damp cloth?

- Is the hairbrush tucked at exactly the right angle for Sasha to find it effortlessly on stage?

- Is it 8 or 10 paper dolls that need bluetacking?

- Has Sam collected the food coupons? Aiyo!

My head, if opened, would’ve spilled out props, checklists, bits of music cues, and a small gust of anxiety.

11:00 am: Technical not-quite-a-rehearsal

Foz gently broke the news: no full tech run. But we could walk through a few bits. Naturally, we tackled the Gamalan section—a tricky new addition Sasha and I had worked out with DFB. As always, Foz reassured us with calm DJ-zen: he’d watch us and cue the music accordingly.

Sasha and I then played our favourite game: Prop Geography—where does the fan come from, where does the hairbrush go, and how many seconds does it take for the bucket to make a dignified exit?

Props, performance, and the ethics of object play

Now, here’s where things got unexpectedly… deep.

DFB, with the persistence of a wise auntie, insisted we form relationships with our props. Not just use them but know them. As a bharatanatyam dancer, I’m trained to evoke entire cosmologies with an eyebrow and a flick of the wrist. Props? Optional. At best. Now, suddenly, I was expected to commune with a clay ball and treat a cardboard fridge as a scene partner.

It’s been a revelation. Most of the time, these objects misbehave. They are stubborn, unpredictable, and occasionally sarcastic. But I’m learning—not to dominate or bend them to my will, but to collaborate. They have materiality, weight, mood. If I want to tell a story through them, I must listen—not perform over them. This shift, from mastery to partnership, has been one of the most quietly transformative parts of this process.

It’s humbling. A dancer used to controlling every gesture must now share the stage—with Sasha, yes—but also with a very moody megaphone and a dozen other unpredictable props.

12:00 noon: The public arrives (and my stomach performs a solo)

Festival gates open. Two hours to go. I try watching other shows to distract myself, but stray thoughts sneak in like uninvited guests:

'Is the fan upright?'

'Was it 10 or 8 dolls again?'

'Should I check the clay’s mood?'

Lunch happens in polite, distracted conversation. Then, in a sacred corner backstage, I unroll my ten-year-old yoga mat and breathe. It knows the weight of my pre-show mind. Thirty minutes later, my body is looser, and my thoughts, blessedly, quieter.

3:15 pm: Showtime, and the discipline of letting go

Then—magic. The moment the show begins, everything drops away. Nerves dissolve. My years of training step in, guiding me into that elusive but essential state of presence. The discipline of letting go is something bharatanatyam training quietly teaches you: not just how to do, but how to be.

Here, in front of a live audience, the only thing that matters is joy. Not polished perfection, but a kind of active surrender—an alertness in the body and spirit that says, this moment is everything. There’s freedom in that, a kind of generosity that performance demands.

Sasha and I squeeze hands like stage comrades. The audience leans in. We begin.

Of voices, watching, and the performer’s split-self

During the show, I hear voices. (Don’t worry—it’s the usual trio.)

David: 'Keep playing.'

DFB: 'Extend the movement—don’t throw it away!'

Foz: 'I’ve got the cues, don’t worry.'

Even as I embody the character, I’m also observing myself—modulating timing, responding to Sasha and the music, adjusting to the gaze of a curious 6-year-old in the front row. That split between performer and internal witness is fascinating: you’re immersed, yet alert. With- in and With-out.

The End. Or just the beginning.

The show ends. We bow. Sasha and I have become closer, bonded through the emotional terrain of wet clay and flying stones. Some audience members are moved to tears—always a good sign (unless it was allergies).

Then comes the real test: coffee with David and Foz.

'Too long.'

'Transitions felt laboured.'

'It should be more like flipping through a cartoon book—clean, playful.'

And so, over the next three shows, we do just that. We play. We trim. We risk new choices. We listen more closely to the music, to the props, to each other. And by Sunday evening, we have something leaner, richer, tighter. Forty-five minutes of distilled story, rhythm, and joy.

David and Foz both say they were moved. Then I exhale.

Because despite every compliment, those are the two whose eyes I’m always trying to catch.

Sunday, 7:00 pm: The clay has settled

As I packed up, I felt… full. Not just tired-full, but artist-full. The kind of full you get when you’ve carried a creative child for two years and finally heard it cry for the first time.

The journey had included every shade of uncertainty—mental mud, emotional bruises, and glorious flashes of inspiration. And somehow, with this mad and brilliant team, we’d made something. A show. A story. A new chapter.

So, no, I didn’t meditate in silk robes or take my breakfast in Monte Carlo. But I did get a cloth fridge to stand tall on stage, made clay speak, and coaxed a paper doll to hold meaning.

And isn’t that something?

The author

Vidya is a performer and creator who combines her expertise in bharatanatyam and ceramics to produce bold, visceral works of physical theatre. Her latest outdoor production, Holy Dirt, is a collaboration with theatre director David Glass. This international project is a UK- India- Korea commission, with support from Arts Council England , InKo Centre( India),Certain Blacks, 101 Creation Centre and ArtAsia.