Seeta Patel’s Rite of Spring

14 May 2019

Birmingham Hippodrome

Reviewed by Magdalen Gorringe

When Igor Stravinsky’s orchestral concert work The Rite of Spring premiered in Paris in 1913 with choreography by Vaslav Njinsky, it was famously controversial. While the supposed ‘near riots’ that greeted the performance are now contested (see Levitz 2017), it is undeniable that sections of the audience were scandalised, both by the ‘noise’ of Stravinsky’s score as well as by what they perceived as the ‘barbaric…shapeless…confused stamping’(Lalo 193, cited in Levitz 2017: 154) of the choreography. The scandalised parties did not, however, prevent Stravinksy, Njinsky and the corps de ballet taking ‘five curtain calls amidst clapping and a few boos’ (ibid.:152).

Since this opening, the Rite of Spring has proved something of a lure for choreographers who have interpreted and reinterpreted it from multiple perspectives, with famous versions including those by Martha Graham, Maurice Béjart and Pina Bausch. Akram Khan choreographed a version in 2013, ItMoI (on which, see Mitra 2015), scandalising at least as many as were originally offended by Stravinsky’s music by using only 30 seconds of the original score (Garafola 2017).

In choosing to create the first bharatanatyam interpretation therefore, Patel is both making history, and stepping into a weighty historical narrative. While an analysis of Patel’s work in the light of this narrative would be fascinating, and a worthy task for an eager MA student, such analysis is beyond the scope of this review which confines itself to an immediate response to the work as seen.

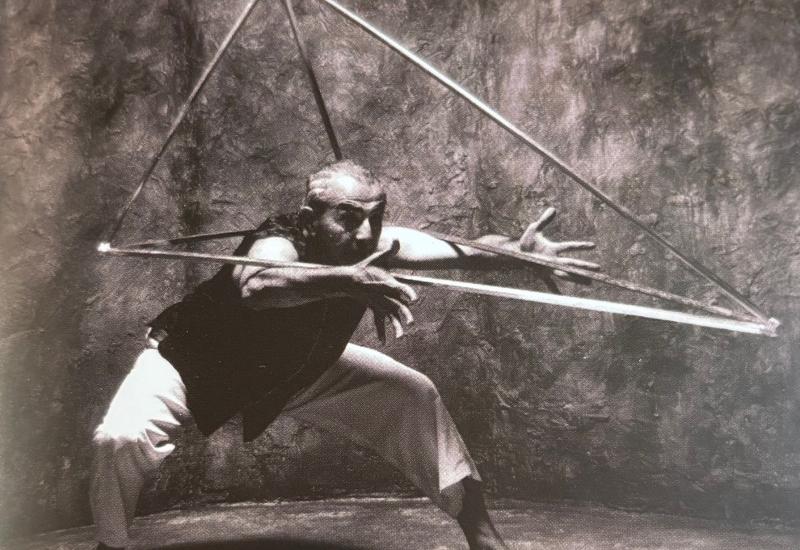

My immediate response, therefore, is that this is a luscious piece of art. I use the word advisedly. From the moment the piece starts, the strength, commitment and virtuosity of the dancers; the quirkily winsome costumes (designed by Jason and Anshu Arora) and the exceptional lighting design of Warren Letton combine to make a sensory experience nothing short of delectable. As if in defiance of the latter-day critic, Patel’s work embraces the percussive stamping of bharatanatyam in a manner anything but ‘shapeless’ or ‘confused’. At times, her choreography weaves the dancers in and out of patterns like a murmuration of starlings – a shape forms for a second only to be replaced seamlessly and invisibly by another. At other times, an image is conjured with the detail of a miniature painting – a tantalisingly androgynous ‘Chosen One’ (beautifully danced by Sooraj Subramaniam) rests languorously on stage, arm carelessly perched on his knee. A sudden swarm of bees gathers round the lotus of his hands. In an ‘interlude’ to two halves of The Rite, against the hypnotic voice of Roopa Mahadevan, the dancers gather on stage in a sequence that in its playfulness and charm resembles nothing so much as Titania and her fairies in A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream. I find myself both thrilled and slightly disconcerted seeing the well-loved movements of bharatanatyam so thoroughly recontextualised. The well-known movements and well-known music combine to make something singularly unknown. I am glad to be disconcerted; to have my perspective on the familiar reconfigured and refocussed. Given his unconventional approach to ballet, I feel sure Njinsky would approve. This is a piece to savour, concluding with a visually and conceptually striking twist to the fate of the ‘Chosen One’.

To fully appreciate the work however, it must be seen in the wider context of South Asian dance in Britain, something that, as Patel made clear in the post-show Q and A, is very much part of her thinking. Intertwined with her artistic vision is a drive to create a sustainable ecology for bharatanatyam dancers in the UK, something evinced in the different curtain raisers for The Rite’s performances, each using young British bharatanatyam dancers. The Birmingham performance opened with Dance Dialogues, a sparky work, performed with punch and panache by three bharatanatyam dancers and three alumni of the National Youth Dance Company. Patel is thinking big – for the next version of The Rite she wants a live orchestra, with double the number of dancers. During the evening, Elaine Heinen offers us a teasing illustration of the power of live music in her stirring rendition of Bach’s Cello Suite 1 – and it doesn’t take much to imagine what this could mean for British bharatanatyam dancers wishing to take dance as a profession. Where there is currently not a single NPO consistently employing bharatanatyam dancers, regular work of this sort and scale could prove revolutionary. All the more so because Patel hopes that the young dancers in her curtain raisers could form part of the cohort for her future works. As Chris Sudworth, Associate Director of Birmingham Hippodrome observed, both Patel’s ‘choreographic boldness’ as well as her ‘reevaluation of what is possible’ for Bharatanatyam in Britain are inspiring. As they say, ‘Watch this space’ !

References

Garafola, L. 2017. A Century of Rites: The Making of an Avant-Garde Tradition in The Rite of Spring at 100, eds. Carr et al, 17 – 28, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Levitz, T. 2017. Racism at The Rite in The Rite of Spring at 100, eds. Carr et al, 146 - 178, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Mitra, R. 2015. Akram Khan: Dancing New Interculturalism, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan