Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution

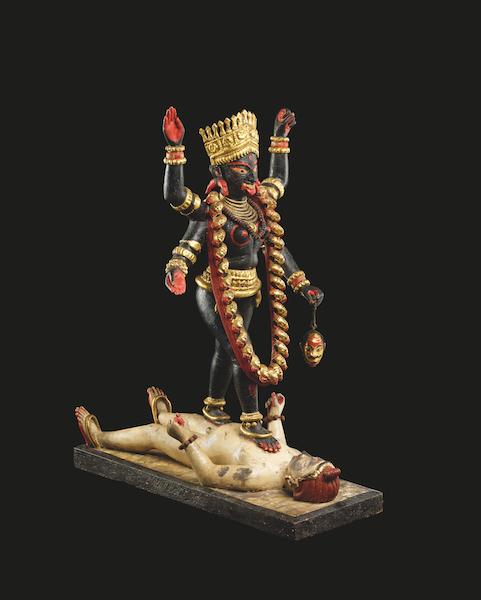

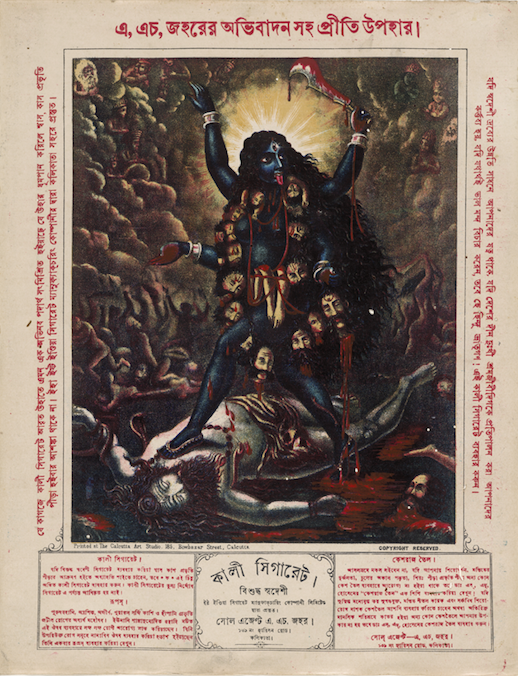

Kali striding over Shiva, probably Krishnanagar, Bengal, 1890s. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution

British Museum, London

Supported by Bagri Foundation

25 September 2020 – 21 January 2021

THIS EXHIBITION IS about everything. It is a stimulating and immensely thought-provoking introduction to Tantra.

The material on display illuminates the depth and reach of the movement that permeated and transformed mainstream Hinduism and Buddhism. Liminal and transgressive, it constantly challenges the orthodox. Some of the objects are devotional, some instructional, others political.

Feminine power, Shakti, is foregrounded in Tantra; and in contrast with the dominant traditions, mortal women were regarded as the natural embodiment and transmitter of Shakti (see Ramos, p. 20). Female Tantric practitioners/goddesses, yoginis, were regarded as particularly powerful. The installation presenting a yogini temple – though quite modest in scale – provides a genuinely immersive experience. It evokes a powerful sense of being on the edge of other realms and possibilities (a bit Philip Pullman). The shape, open to the skies, is almost an antithesis of towering Hindu temples, and indeed of the Shiva Linga (which is not a feature of Tantric imagery, focusing as it does on the feminine). Significantly, these temples were not hidden, but visible.

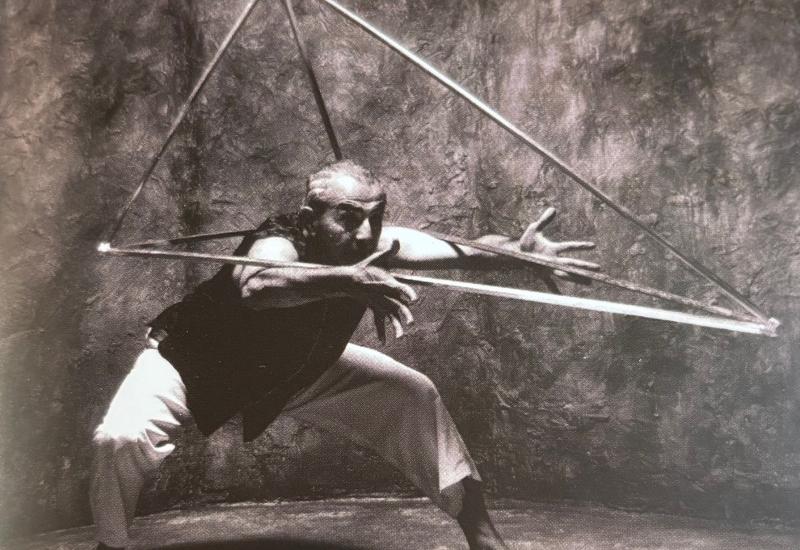

Catalogue Fig. 34. Courtesy British Museum

The erotic sculpture familiar from many Hindu temples was not necessarily Tantric. The Tantric images are transgressive, breaking pollution taboos. In Tantric Buddhist teaching, the divine union between wisdom (female) and compassion (male) is presented in an object for meditation. The practitioner meditates on the image – in this example, Raktayamari in union with Vajravetali, who trample on Yama (the Hindu god of death), breaking the cycle of rebirth and suffering – internalises it and identifies with it.

©The Trustees of the British Museum

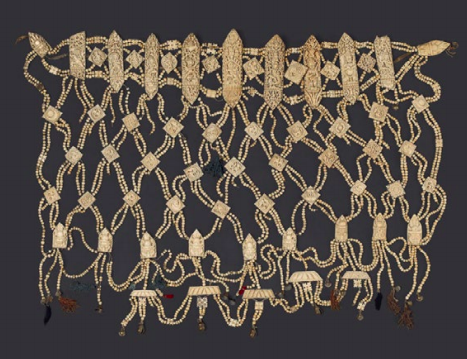

More ‘transgressive’ than this, perhaps, is the example of the bone apron, made of pieces of intricately carved human bones, probably from a charnel ground, worn for ritual dance; again, with the same end, to become the deity. The care taken in the preparation of human bones for a devotional ritual is a practical demonstration of the idea that everything is sacred, nothing is polluted or polluting.

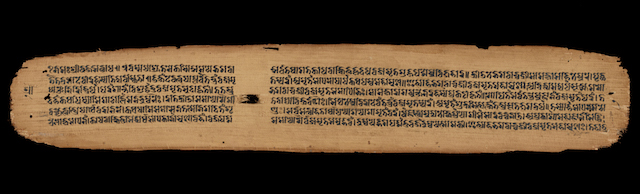

Then there are the instructional objects: on display are 12th-century palm-leaf manuscripts from Nepal, with instructions in Sanskrit for reciting mantras and carrying out rituals to invoke the presence of a goddess or god;

Cat. Fig. 7

and, from the tradition of Hatha Yoga (which was especially popular from the 16th century), there is a delicately-painted 19th century scroll consisting of seven panels, from Rajasthan. This elite visual Tantric guide depicts an abstracted yogic body with Kundalini, the source of Shakti, as a serpent. In the panel illustrated here, the second from the bottom of the scroll, Brahma, the god of creation, appears in a yellow lotus in the svadhishthana chakra (genital area). He is followed by intersecting triangles representing the union of feminine and masculine principles and the red and coiled Kundalini.

The goal of the practitioner was to arise from the unconscious, to awaken the goddess, to enable her to rise through the chakras, the energy centres, and transform the yogic body and achieve liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

Kali, the ferocious yet compassionate Mother, expression of the divine feminine energy, was a popular focus of devotion in Bengal and elsewhere (Ramakrishna had been a devotee and Tantric practitioner). She became a subversive image as anti-colonial revolutionaries adopted her as a personification of India and a symbol of resistance. The image below was used to advertise the domestically-produced ‘Kali Cigarettes’, as part of the movement to boycott British products. The garland of heads around the goddess’s neck looked suspiciously British, and It was later banned because of this.

(Bengal, India), about 1885–95. ©The Trustees of the British Museum

Kali, and Tantric images and practices rattled the British, not least Christian missionaries. Those brought up on images of a crucified Christ were perhaps more bothered by the sex – or female dominance – and taboo-breaking than the violence. (One could compare the process of meditation on and identification with a suffering Christ that had been part of medieval Christian devotional tradition.)

One of the last images in the exhibition, ‘Housewives with Steak-Knives’ is a vibrant feminist take on Kali. The muscular figure with her hairy armpits wears a garland of the heads of patriarchal and colonial figures. Her flag shows two paintings by the great female artist Artemisia Gentileschi depicting the decapitation of Holofernes by Judith with the help of her maid – two women exercising justice. Gentileschi, one of the most important women artists, had been raped by her father’s assistant.

Medium: oil, acrylics, pencil, collage, white tape on paper on canvas.

2450mm x 2220mm. © Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2019.

The exhibition shows the wide appeal of Tantra through the ages. It was inclusive, so that marginalised figures – women, outcastes – were drawn by it. There are associations with other outsider groups, Sufis and Bauls. The prospect of power was one of the aspects that attracted those in courtly circles. Its symbolism lends itself both to personal and political liberation.

Publication accompanying the exhibition: Imma Ramos, Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution (Thames & Hudson and British Museum, London, 2020)