Between the Lines – Re-thinking Tagore for the 21st Century

By 2014, the UK had seen many performances and events marking the 150th anniversary of the birth of Rabindranath Tagore in 1861. Pulse was prompted to bring together writers, singers, dancers and scholars to explore the place of Tagore – at once, and somewhat paradoxically, an artistic iconoclast and a weighty pillar of Bengali culture – in the 21st century. It was a day of explorations, performances and critical enquiry into Tagore’s work.

Between The Lines –

Re-thinking Tagore for the Twenty-First Century

Sunday 2 November 2014 Rich Mix

Some important themes emerged in the course of the day. For Bengalis, whether in India or in the diaspora, Tagore had been a pervasive presence through childhood. For some this had felt oppressive and had the effect of producing a resistance to Tagore. Major contributing factors to this resistance, particularly in the diaspora, were the conventions that had built around performance practice, as well as lack of sufficient familiarity with the Bengali language. Much of the performance experienced was also of not very high quality. However a common experience was for youthful resistance to give way, with greater understanding, knowledge and the capacity to explore Tagore’s work in one’s own way: this made it possible to turn to Tagore afresh.

Many of those who came to Tagore did so from other directions – they had not been put off by a Bengali upbringing. The day showed that given the opportunity to create work free of existing conventions and expectations, Tagore most certainly belongs in the 21st century and not just to the past, whether in literature, art, dance, drama, music or film. The day affirmed the value, indeed necessity, of an intellectual underpinning to the examination of Tagore’s work, together with a sharing of critical analysis.

In conversation with Ansuman Biswas of the Tagore Centre, Amit Chaudhuri spoke of Tagore’s ubiquitous presence through his childhood and his own relationship with him. He described the cultural and historical fabric of which Tagore was a part, positioning Tagore at the cusp of modernism, with an account of the development of the ‘bhadralok culture’ through the 19th century. Chaudhuri spoke of the development of ‘secular sacredness’; of the dismantling of old religion, of Brahmo Samaj and the poetry of space and light; of how the sacred is implicit, not visible. He considered Tagore’s interest in the way Bengali nursery lines work, subverting logical expectations and rationality to make space for the random, introducing William James’s notion of ‘stream of consciousness’; he spoke of Tagore’s ‘unfinished moment’; his use of collected tunes in completely different contexts; and of his work as experimental and avant-garde. Chaudhuri’s view was that the time was now ripe for re-discovery, for in Kolkata Tagore is even more ubiquitous than before in ways which run counter to the irresponsible freedom of ‘chhuti’ (holiday); and elsewhere, as with ‘Banga Shammelan’ in North America, Tagore is presented in a way which runs counter to the way Tagore himself would have thought, for Tagore himself was not reverential at all: the best practitioners are without reverence. Rabindra Sangeet should be taken back towards akar rather than okar with its more constricted syllables.

The singer-songwriter Sahana Bajpaie grew up at boarding school in Santiniketan, where Tagore’s presence was everywhere but far from oppressive. The children sang with utensils, bowls and spoons, then with a tanpura, not the detested harmonium. They were taught how crucial it was to understand the lyrics they sang as the audience would realise if they didn’t. She pointed out that Tagore drew on all kinds of music – including Baul music, Irish and Scottish folk music, Hindustani light classical – and that he was unwilling to accept any music as sacrosanct. She commented that Tagore was well-versed in political, social and gender issues; and that he re-invented.

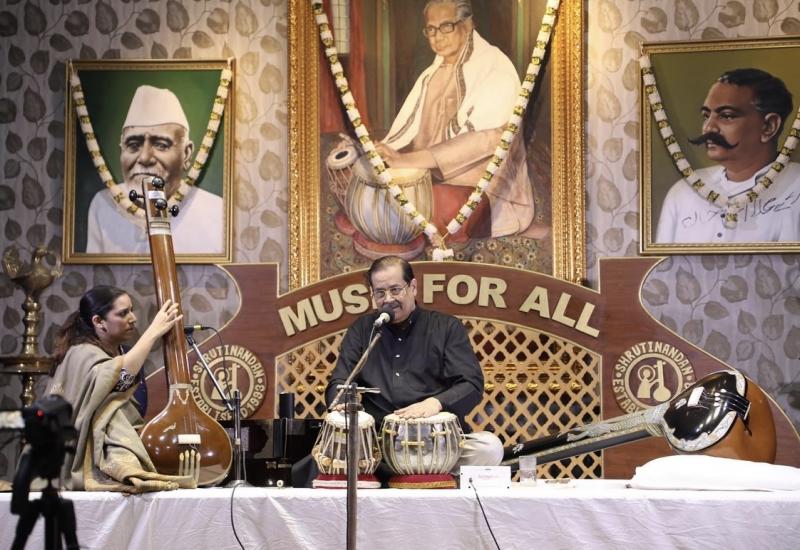

Matthew Pritchard, who works on Musical aesthetics, spoke as a listener rather than as a singer, though a singer ‘in the mind’. Tagore had said ‘sing my songs in the bathroom’ and advocated singing with the naked voice. Pritchard’s view was that when accompaniments steamroller over the songs the emotion is lost. It has become accepted to use the harmonium and tabla, but the problem is that harmonisations don’t work. Matthew demonstrated this (to comic effect), with the keyboard.

Sohini Alam (a British singer of Bangladeshi descent) explained that her band Khiyo, with Oliver Weeks, had been formed in direct response to what Matthew had described. A child in a Bengali family of musicians, she had been made to learn Tagore as well as classical and Nazrul songs and found this ‘quite stifling, suffocating’. Unlike Bajpaie, she learned with harmonium and tabla. The recordings available were those with the terrible ‘circus music’ accompaniments she was unable to block out. She had to grow out of that and also to learn Bengali to appreciate Tagore. Meeting Oliver was a blessing: he knew Bengali and was able to harmonise without driving a steam-roller over the song. Khiyo would like to be able to convey the music to non-Bengali audiences.

Playwright Tanika Gupta‘s parents had founded ‘The Tagoreans’ in 1965. With a minibus her pioneering parents took Tagore’s dance dramas to Austria, Germany and the Netherlands; but Gupta had felt somewhat stifled by Tagore. She wanted to write but not about Tagore. At 16 she was sent to Santiniketan for ‘de-Anglicisation’. There she learned Bengali. Though she had vowed never to touch Tagore in her writing, she told of how the stories came back to her as she realised that he wrote about what mattered – humanity.

Film-maker Sangeeta Datta talked of Tagore’s excitement over film, and when invited to direct a film he made a version of his play Natir Puja, ‘The Dancing Girl’s Worship’. He brought ‘respectable’ girls onto the stage for the first time.

Writer Sharmila Chauhan, a Gujarati, had come to Tagore fresh, from a British-Asian perspective. Her own work embodies some of the emotional complexities of being a woman found in Tagore’s work. She talked about how she looked at Tagore’s women in different works, with the themes of self-sacrifice/martyrdom, asking how much power do I as an Asian woman have? Is a woman’s power about her beauty?