Between The Lines – Re-thinking Tagore for the Twenty-First Century

Between the Lines – Re-thinking Tagore for the 21st Century: a day of performances, explorations and critical enquiry. Sunday 2 November 2014, Rich Mix, London.

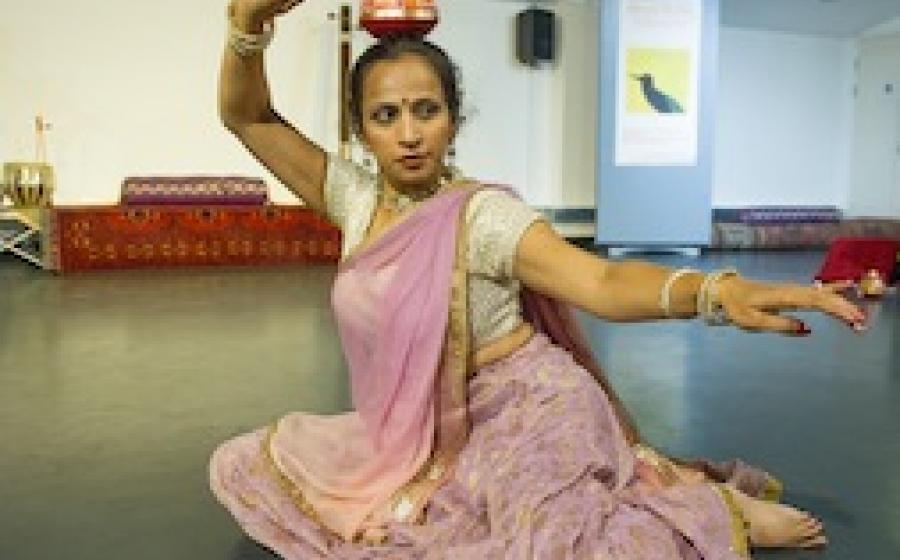

Photos: Arunima Kumar & Sohini Alam | Urja Desai Thakore | Amit Chaudhuri with Ansuman Biswas | Credit Simon Richardson

Between The Lines – Re-thinking Tagore for the Twenty-First Century

On a wet November day, the long room of Venue 2 at the Rich Mix was set with rugs, bolsters, a vase of tall red roses and a few chairs. We removed our shoes before entering for our day of explorations, performances and critical enquiry into Tagore’s work.

Some important themes emerged in the course of the day:

- For Bengalis, whether in India or in the diaspora, Tagore had been a ubiquitous presence through childhood.

- For some of the speakers/performers and audience, this had felt oppressive and had the effect of producing a resistance to Tagore.

- Major contributing factors to this resistance, particularly in the diaspora, were the conventions that had built around performance practice, as well as lack of sufficient familiarity with the Bengali language. Much of the performance was also of not very high quality.

- A common experience was for youthful resistance to give way, with greater understanding, knowledge and the capacity to explore Tagore’s work in one’s own way: this made it possible to turn to Tagore afresh.

- Many of those who came to Tagore did so from other directions – they had not been put off by a Bengali upbringing.

- The day showed that given the opportunity to create work free of existing conventions and expectations, Tagore most certainly belongs in the 21st century and not just to the past, whether in literature, art, dance, drama, music or film.

- The day affirmed the value, indeed necessity, of an intellectual underpinning to the examination of Tagore’s work together with a sharing of critical analysis.

More Photos of the participants by Simon Richardson

Synopsis of the day’s events

The opening

Ansuman Biswas live artist and current Artistic Director of the Tagore Centre, gently directed the audience to walk around, hum and say ‘more’, as poem 58 from Gitanjali was read. Dancers responded to the words with their movements and vocalists and audience members were invited to sing.

Amit Chaudhuri in conversation with Ansuman Biswas

Amit spoke of his own relationship with Tagore and of Tagore’s pervasive presence through childhood.

He placed Tagore in cultural/historical context: he described the cultural fabric of which Tagore was a part; he positioned Tagore at the cusp of modernism and gave an account of the development of the ‘bhadralok culture’ through the 19th century.

He talked of the development of ‘secular sacredness’; Brahmo Samaj and the poetry of space and light; how the sacred is implicit, not visible; Tagore’s interest in the way Bengali nursery lines work and stream of consciousness; the ‘unfinished moment’; Tagore’s use of collected tunes in completely different contexts; his work as experimental and avant-garde.

Amit’s view is that the time is now ripe for re-discovery, for in Kolkata Tagore is even more ubiquitous than before in ways which run counter to the irresponsible freedom of ‘chhuti’ (holiday); and elsewhere, as with ‘Banga Shammelan’ in N. America, Tagore is presented in a way which runs counter to the way Tagore himself would have thought, for Tagore himself was not reverential at all. The best practitioners are without reverence.

Rabindra Sangeet should be taken back towards akar rather than okar with its more constricted syllables.

Sahana Bajpaie: The sources of Rabindra Sangeet and studying in Santiniketan

During Sahana’s childhood at boarding school in Santiniketan Tagore’s presence was everywhere but far from oppressive.

The children sang with utensils, bowls and spoons. Tagore’s voice had been praised and he liked to sing a capella. The children sang with a tanpura, not the detested harmonium. They were taught how crucial it was to understand the lyrics they sang: the audience would realise if they didn’t.

Sahana sang the Baul (wandering minstrel) song, Shohoj Manush. Tagore drew on Baul music, Irish and Scottish folk music, Hindustani light classical – he was the first to translate Hindi bandishes into Bangla. He was unwilling to accept any music as sacrosanct.

Tagore was well-versed in political, social and gender issues. He re-invented.

Sahana sang Ami kaan pete roi.

Matthew Pritchard: Extracting the essence: what makes Rabindra Sangeet what it is?

Matthew spoke as a listener rather than as a singer, though a singer ‘in the mind’: Tagore said ‘sing my songs in the bathroom’. He advocated singing with the naked voice. When accompaniments steamroller over the songs the emotion is lost. It became accepted to use the harmonium and tabla: the problem is that harmonisations don’t work. Matthew demonstrated this (to comic effect), with the keyboard.

Sohini Alam and Oliver Weeks: The process of creating their interpretation of Amar Sonar Bangla

They performed their stripped-down version of Amar Sonar Bangla.

Sohini explained that their band Khiyo had been formed in direct response to what Matthew had described. A child in a Bengali family of musicians, she had been made to learn Tagore as well as classical and Nazrul songs and found this ‘quite stifling, suffocating’. Unlike Sahana, she learned with harmonium and tabla. The recordings available were those with the terrible ‘circus music’ accompaniments she was unable to block out. She had to grow out of that and also to learn Bengali to appreciate Tagore.

Meeting Oliver was a blessing. He knew Bangla and was able to harmonise without driving a steam-roller over the song. They want the singer and musicians to be able to convey the music to non-Bengali audiences.

Song of the City Dancer: Kali Chandrasegaram

Kali danced against the backdrop of the city through the long window. It was a moving and expressive re-working of Shobna Gulati and Bisakha Sarker’s choreography, avant-garde when it was created 20 years ago and as powerful now.

Rishi Banerjee Putra: male characters from Tagore’s dance dramas.

There was no getting away from Tagore as a Bengali growing up in Manchester. Rishi wanted to explore characters not much looked at in Tagore’s work. He spoke of performance and the need for the dramatic element.

Tanika Gupta Growing up in a Tagore household

Tanika told the story of how her mother fell in love with her father’s voice before she ever saw him as he used to sing on the way to college in Santiniketan.

In England, Tanika and her brother grew up with The Tagoreans. She would awaken to the sounds of singing and dancing (her mother danced) in the mornings. With a minibus her pioneering parents took Tagore’s dance dramas to Austria, Germany and the Netherlands.

Tanika had felt somewhat stifled by Tagore. She wanted to write but not about Tagore. At 16 she was sent to Santiniketan for ‘de-Anglicisation’. She learned Bengali and ‘had a fantastic time’. Though she has vowed never to touch Tagore in her writing, the stories come back to her as she realised that he wrote about what mattered – humanity. She found she couldn’t get away from him: at Stratford, where her play The Empress was being staged by the RSC, she came upon a bust of Tagore in the garden of Shakespeare’s birthplace.

Sangeeta Datta Tagore and Film

Sangeeta gave us an overview of films and Tagore: Tagore was very excited by film and when invited to direct a film he made a version of his play Natir Puja, ‘The Dancing Girl’s Worship’. He brought ‘respectable’ girls onto the stage for the first time.

She spoke of a number of Bengali directors who adapted his stories (Satyajit Ray, Bimal Ray, Tapan Sinha and recently, Rituparno Ghosh with a bi-lingual film); and her own films (including Letter from an Ordinary Girl).

Sharmila Chauhan Tagore’s Women

Sharmila is a Gujarati and came to Tagore fresh, from a British-Asian perspective.

Her own work embodies some of the emotional complexities of being a woman found in Tagore’s work. She talked about how she looked at Tagore’s women in different works, with the themes of self-sacrifice/martyrdom, asking how much power do I as an Asian woman have? Is a woman’s power about her beauty?

Sudipta Roy Tagore and Raag Behag

Sudipta sang Jyotsna Raate, set in Raag Behag and talked about Tagore’s use of the Raag. This picked up on Sharmila Chauhan’s points about Tagore’s exploration of the nature of female feelings in a man’s world, something we were unable to talk about a generation ago.

Memories, Dreams and Reflections: audience members wrote down favourite quotes or thoughts inspired by the day and attached them to the drawing of the Tree of Life on the wall, signifying the trees under which students sit in Santiniketan.

Works in progress

Mahapraan

This new commissioned work was jointly produced by choreographer and dancer Urja Desai Thakore and composer Mrityunjoy.

The piece is inspired by Tagore's poem Praan and its Gujarati translation by Jhaverchand Meghani. The work presented the two aspects of life, destruction and creation, linking them to the Almighty.

Dancer / choreographer: Urja Desai Thakore | Composer : Mrityunjoy | Singer : Aritro Bhattacharya | Cello : Nicole Collarbone | Gujarati narration : Abha Desai | Advisor : Anuradha Roma Choudhry

The Curse

An excerpt from one of Tagore’s epic poems, Biday Abhishap, in a 2014 setting, presented as a blend of classical and abstract kuchipudi dance theatre with original music set to Tagore’s words.

Devayani speaks of her past with Kacha, son of Brihaspati, guru of the gods. The two fell in love, but Kacha left Devayani to fulfil his duty to the gods by teaching them the secret of immortality. Faced with rejection, she cursed him so that he would never be able to use his knowledge again. We question whether it is Devayani who remains the cursed one.

Dancer: Arunima Kumar | Vocals: Sohini Alam

My Soul Is Alight

‘I run as a musk deer runs in the shadow of the forest, mad with his own perfume...’ Excerpts from The Gardener – Tagore’s cycle of love poems – are the inspiration for this work-in-progress. A human and spiritual struggle. An overwhelming and elusive desire. The potential to attain unity with the infinite.

Vocals, composition: Ranjana Ghatak | Dance, choreography: Katie Ryan | Spoken rhythm, advisor: Parvati Rajamani

Q & A with the artists. Chaired by Sanjeevini Dutta.

Urja had never worked on Tagore before. As a kathak dancer she was attracted to the strong rhythms of the poem she chose. She visualised the idea of Durga, the life-force, with flames. The music and choreography went hand-in-hand. She was clear that she didn’t want any electronic music.

Sohini & Arunima: Arunima had worked with Tagore before, and found it ‘spiritual, beautiful’. Sohini suggested they work with this powerful and expressive piece on duty versus love. Arunima wanted to keep an element of the foot-painting traditional in kuchipudi. Sohini played the cajon and sang a capella. The dancer and the musician in this piece were both integral, not separate. The Bengali was onomatopoeic. The English followed the trajectory of the woman’s life.

Katie & Ranjana: The dancer and the musician had both wanted ‘one voice’ to the piece. Katie: ‘Am I the inner dancer in Ranjana’s head and is she the inner voice in mine?’ Was there a conflict?

Shared creations

Jean Riley read her poem Tagore Watches (after Tagore’s The Ferry) and Tagore’s The Ferry (trans. Ketaki Kushari Dyson). Jean discovered Tagore’s poetry at Dartington this summer.

Runi Khan was born Indian, became Pakistani, then Bangladeshi and is now British: but she was always Bengali first and Tagore was always present. She spoke of Tagore’s works for children and feels a need to find ways to bring Tagore to children, as she did with Robi’s Garden. She spoke about Rezwana Chowdhury Bannya's ' Music for Development ' school for slum children in Dhaka which predominantly teaches Tagore's music. The children have to return to the darkness of the slum, but they in turn teach others.

The day closed with Rishi Banerjee singing Ami rupe tomay bholabo na.