Darbar Festival 2018: Adventures in Odissi and Kathak

Darbar Festival 2018

Adventures in Odissi and Kathak

25 November, 2018

Sadler’s Wells

Reviewed by Donald Hutera

This was the second of the two dance evenings presented at Darbar Festival 2018, which is also the second year dance has featured on the Festival programme.

The night placed a pair of female soloists, odissi dancer Sujata Mohapatra and kathak specialist Gauri Diwakar, in the spotlight. The ability of these uniquely talented artists to claim the main stage of Sadler’s Wells wasn’t in question. To some extent, however, the showcase-like format and tropes of the performance and, for this Westerner, the lack of a fuller understanding of context, contributed to the feeling that their initial welcome had been worn out. Sadly, over time my admiration for and appreciation of their gifts began to erode.

Mohapatra is a bright, comely and exacting performer who radiates confidence and a skill that could just about be patented. After a deft invocation (flower petals deposited downstage, and nods to each of the four musicians as she passed by them while making a sidestepping circle round the stage) she executed an introductory dance that serves as a display of her wares. Her footwork was fast and sure, her sense of rhythm astute, and her movements neatly contained within what I perceived as the invisible sphere around her.

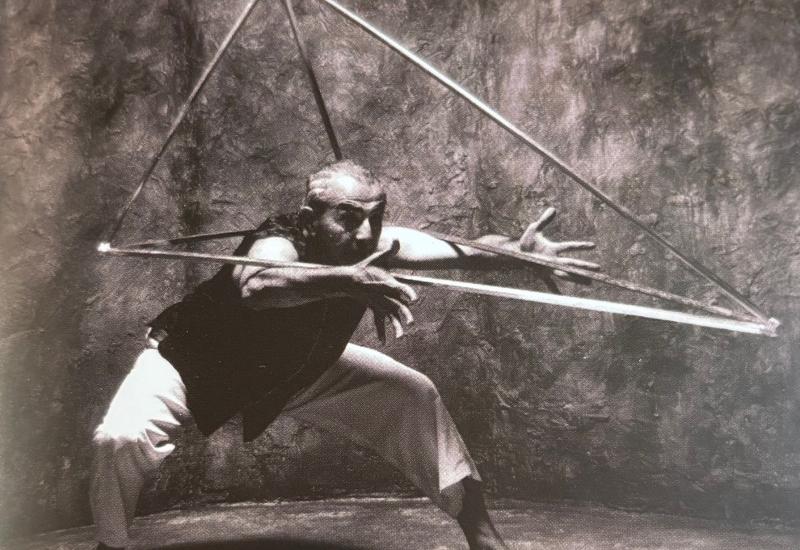

The bulk of her performance, however, was a piece of storytelling from the Ramayana. The tale she was about to embody was summarised for us via a male voice-over in the dark. It was long and relatively complicated, and for me not entirely audible, but I let go of any anxieties I might have felt as an ill-informed ‘outsider’ and trusted that I’d surrender to Mohapatra’s interpretation. As it turned out, I may not have always ‘got’ what was going on, or precisely when Mohapatra was meant to be Rama, Sita or Lakshmana, but I know she always knew what she was doing. Her clarity of characterisation and pace were unwavering, and her opening image, poised with bow and arrow (mimed, of course), strong. I can still see her making kneeling strides across the stage, gambolling about as a deer and using her fingers as tail and ears, or transforming into a deity. But again, my one cavil is that if you can’t follow a given narrative thread there’s a risk that what you’re watching will become meaningless.

Diwakar danced ‘Hari Ho…Gati Meri’ (‘Let my salvation be in the supreme’), a work inspired by the words of four Muslim poets and choreographed by her guru, Aditi Mangaldas. Glowing in a series of pale gold or yellow costumes, Diwakar was suffused with a varying energy – soft and smooth, or propelled by attack; airy here or liquid there – very much in keeping with kathak form. She swooped and spun, arms carving the air or a lone hand fluttering like a flame that spread to ignite her body. She also possesses a vibratory stillness, a state of being either leading to or from a sudden, swift burst of rapid motion.

Diwakar’s lighting – a repeat of last year’s striking teardrop installation of 400-some suspended bulbs, co-designed by Aideen Malone and Festival dance curator Akram Khan – was better-tailored to her performance than Mohapatra’s. For the latter it was an arcing canopy, whereas lines of light rippled above Diwakar as if imbued with a living spirit to which she could readily respond. I understood that Diwakar was both assertive and receptive during what could be deemed the physical manifestation of an internal dialogue between her and a close yet elusive Krishna (the subject of the source poems). But, as with Mohapatra, I reached a point where I no longer felt privy to the dance and its deeper meanings. I could witness Diwakar’s joy and exuberance (fuelled, in part, by the storming Ashish Gangani on the pakhawaj and Yogesh Gangani’s galloping tabla playing) without, ultimately, sharing it.

Finally Khan introduced a duet created by the two dancers in just a week. This was an overextended coda, respectful, caring and nice enough in its way, without creating any sparks or, as was the case with Mavin Khoo’s bharatanatyam duet on the previous evening, breaking new creative ground. Less might’ve been more.