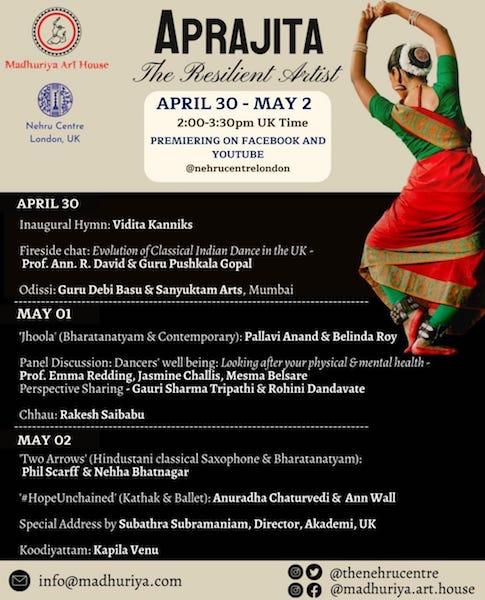

Aprājita, The Resilient Artist

Aprājita, The Resilient Artist, was a three-day virtual dance festival curated by Kripa Iyer and Neelambaree Prasad. Childhood dance friends in Mumbai who eventually found themselves as neighbours in London, they established Madhuriya Art House to share their love for the Indian classical arts. By collaborating with London’s Nehru Centre via their online platforms, Kripa and Neelambaree continued to use dance to nurture individual psyche and community well-being by focusing on the ideas of strength and resilience.

The first day began with an invocatory hymn, soulfully rendered by Vidita Kanniks. It imagined the spirit of Aprājita as Sarasvatī, the goddess of learning and eloquence, and called on our collective conscience for wisdom and graciousness.

In a ‘fireside chat’ session, Professor Ann David and senior bharatanāṭyam artist Pushkala Gopal recounted the history of Indian dance in the UK, reminiscing about the individuals and institutions who championed interventions and exchanges in order to gain recognition. What we consider ‘progress’ was only evinced through political and cultural gymnastics from its practitioners to bring about change and acceptance. One has to admire their indomitable spirit, and be thankful for the paths they’ve cleared for future generations.

Mumbai-based Sanyuktam Arts, led by artist Debi Basu, opened the performances with Eki lābonye pūrnō prāṇa, calling on the spirit of nature to replenish the soul. The choreography in the odissi idiom came to life through the blossoming of hand-gestures, the cascading of spatial patterns and the graceful transitioning between intricacy and stillness.

Later in the programme we saw more familiar abhinaya (expressive) works from the repertoire of legendary guru Kelucharan Mohapatra. Ahē Nīla Saila recounted tales of Viśṇu’s heroisms, and petitioned that same deity as Jagannātha of Pūri.1 Debi Basu performed Priyē-cāruśīlē showing a repentant Kṛṣṇa using flattery to win back his dejected Rādha. The ensemble closed with Durgā Stuti, a denouement of the female principle as mother goddess and champion warrior.

The highlight for me was the pallavī, an exposition of rhythm and melody. A gentle gravity connected the dancers, as the choreography fanned, inverted and rotated about the space in kaleidoscopic fashion. Transitions from one sculpturesque moment to another were viscous and unhurried, giving work a soft aura. Belying this nonchalance were the arasās (rhythmic compositions)—creeper tendrils effortless and ornate—tripping us up with mathematical complexity, held together by the lattice-like tāla (circumventing time cycle). How uncanny that the tahia—the frilled headdress made from reeds and worn around the hair bun like a halo—reflected these fractal principles in its floral patterns! 2

The lilting melodic refrain of the pallavī, set to the hauntingly sweet rāga Madhuvanti, was the richer for being played by a traditional orchestra; being partial to acoustic instruments, I was thankful that synthesisers and electronic effects were absent!

I’m convinced that it is in such abstract, non-prescriptive work—through the simple act of being—that truth finds the most convenience to reveal itself. This was such a wonderful piece that I watched it several times!

Day Two began with Jhoola, dwelling on the swing-like impermanence of life. Pallavi Anand (bharatanāṭyam) and Belinda Roy (contemporary techniques) appeared side-by-side in a home studio, finding parallels in repetitive undulating movements. Pallavi then depicted a landscape of heat and dearth; in the midst of this came an unexpected tenderness—a sapling holding on tenaciously to life—offering the dancer a calm resolve. Feeding the concept into the physical choreography, the dancers swung in and out of our view. A rhythmic to-and-fro between percussion, melody and recitation suggested a type of conversation, echoed in the dance as a desire to connect with one another. It was a reminder that in our ephemeral existence we have but fleeting moments to find resonance in our common humanity.

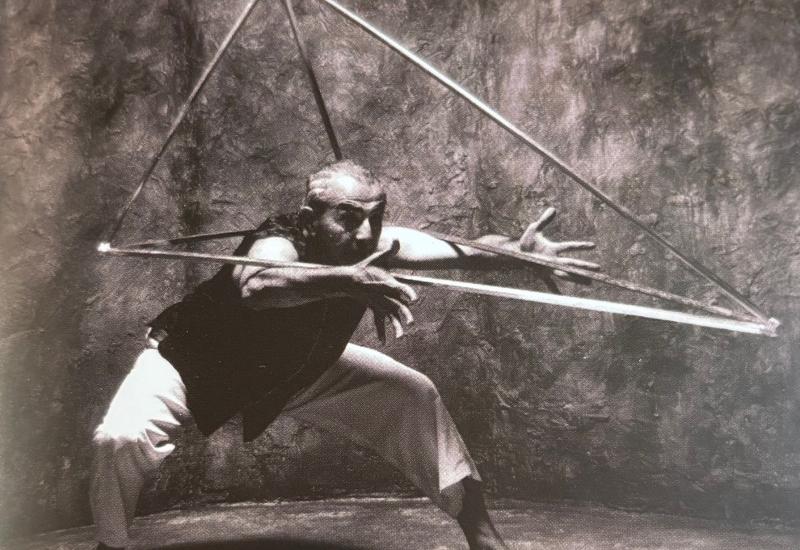

The finale was Mayurbhanj Chhau (a martial dance form from Odisha) by Rakesh Sai Babu and his Trikayaa Dance Company from Delhi. It opened with a solo tribute to Śiva the lord of Dance, which was followed by an invocation of Garuḍa the celestial eagle. Yōdha celebrated the martial roots of the Chhau style by using broad postures and robust barrel turns, and included the use of sword and shield. The group finale, Nāṭaki, was a joyful celebration, expressing intricate footwork and wide movements in high tempo and with great vigour.

The central panel discussion, covering individual as well as industry practices that affect a dancer’s health, forced me to reckon the ways in which to sustain my practice as I give up some of the insouciance of youth. Jasmine Challis offered insights on appropriate nutrition to sustain our bodies. Mesma Belsare spoke on Ayurvedic practices that encouraged us to view ourselves as being a part of an interactive, wholesome system of nature. Gauri S. Tripathi shared her discoveries of balancing (traditional) training methods with an understanding of anatomical mechanisms. Prof. Emma Redding’s recommendation for dancers was to return to practice gradually, and to build strength with care and consideration. Rohini Dandavate spoke of health in terms of social cohesion: having moved to the US many decades ago she has employed the Indian aesthetic and dance practice to help bridge cultural distances and foster understanding.

Relating these ideas to experience, I’ve found transposing studio work to domestic spaces or via Zoom to be neither physically nor mentally sustainable. Even as we acknowledge the physical demands (and injuries sustained) by artists we continue to place the onus on the individual to invest in their own recuperation outside of working hours, often putting their continuity with projects and the longevity of their careers at risk. Will there come a time when coaches and therapists become indispensable members of any working company? While ‘the show must go on’ may seem like resilience, it overlooks the cost of inadequate rest or mismanaged injuries in the pursuit of ambition. My take-away from this session is that resilience would mean cutting out the deadwood from old practices with a willingness—nay, a necessity—to adapt to new, healthier ways of working.

The final day of Aprājita began with Two Arrows, a collaboration between Brisbane-based bharatanāṭyam dancer Nehha Bhatnagar and Boston-based Hindustāni-saxophonist Phil Scarff. Using the metaphor of being assailed by arrows, Nehha depicted the hardships and anxieties we face, and the ensuing spiral of negative emotions that afflict us; she concluded by advocating for equanimity in our thoughts and actions. While I remain curious about the choice of an idyllic suburban park for a background, the use of subtitles was a clever addition, offering a solution to the much-debated concern over the deciphering of the coded languages of Indian dance.

In #HopeUnchained Anuradha Chaturvedi (kathak) and Ann Wall (ballet) performed to a collage of poetic recitation (John Clare’s ‘Instinct of Hope’), paḍhant (mnemonic recitation from kathak), Hindustāni classical and contemporary music. The performers, meeting on split-screen, sought resonance in each other’s styles via the syncopation of graceful arm movements and rapid footwork. The work closed with the dancers leaving their rooms for the outdoors, perhaps as a message for us to look beyond our cloistered worlds.

As a short interlude, Subathra Subramaniam, director of Akademi, lent a message of hope, lauding the creativity and diversity of expression of the artists involved.

The closing act was a performance of kūdiyāṭṭam by the artist Kapila Venu. In the relative absence of lyrics or melodic instruments, on a landscape of percussive refrain, and under the lone light of the nilavilakku (standing oil lamp), this ancient Kerala theatre form displayed a sophistication we’ve come to expect of contemporary minimalism. It is easy to rhapsodise the lexicon of highly-coded hand gestures, the extraordinary control of facial muscles or the ocular calisthenics, but one appreciates that each of these elements is imbued with greater intent: coalescing to facilitate a dense narrative. The story today was Kāliyamardanam, the defeat of the river-serpent Kāliya by the pastoral god Kṛṣṇa.

The communicative success of this performance rested on the fact that the characters were, as in life, multidimensional: Kṛṣṇa was as considerate as he was exacting; Kāliya—our unassuming villain, and quite possibly a victim of circumstances—was brash, protective and eventually repentant. The excitement for me lay not in the outcome—who doesn’t know the end of a millennia-old fable?—but in the telling; the work merely exposed the human condition, and left any moralising to the spectator’s reflections. Esoteric as the form seems, it is a testament to its transportive power that I came away feeling party to the revelation of some truth, by the making of a partnership between artist and witness.

The Aprājita festival was born in response to lockdown-conditions to facilitate the sharing of dance while being physically distanced, and ultimately to uplift spirits during these times of uncertainty. Whilst appreciating the conviction of so many passionate artists, I struggled at times to reconcile the aloofness of such beauty.

I remind myself that art is integral to our lives; Indian dance, with its poetic richness and sophisticated techniques, allows one to soar into a nebula of the sensuous. The value of art, therefore, lies in its abstraction, its effects on us oblique.

But working in the isolation of these experiences is tantamount to being in an echo chamber: not considering our actions on the wider world is to perpetuate the myth of perfection and the illusion that self-awareness has been attained—there is yet a raging pandemic and a world that’s hurting either from our inactions or misdeeds. Resilience is perhaps not simply to keep producing moments of escape, but to use our privileged positions as meaning-makers to decide how we make art. I’m interested in the ethics of art-making as much as in its offer of poetic delights.

I consider some of the things this festival as achieved: it has inclusively programmed established and emerging artists side-by-side; it has creatively reimagined where art is made and shared; it has hosted dialogue and promoted introspection; it has connected artists and collaborators from around the globe to work towards a shared goal. It continues then to use dance to nurture the individual and nourish the community.

There are other issues that continue to beset us, but I think it’s possible yet to make art without slipping either into self-indulgence or feeling martyred by the weight of the world. In resilience thence shall we find the balance, allowing us to apply good conscience and therefore make great art.

The festival continues to be available via these links:

Aprajita Day 1

Youtube: https://youtu.be/d2G_xV1LkOs

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/473217986136717/posts/2927441967380961/

Aprajita Day 2

YouTube: https://youtu.be/XMgogIfyuXE

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/473217986136717/posts/2928255367299621/

Aprajita Day 3

YouTube: https://youtu.be/UggtBmGmhKw

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/473217986136717/posts/2928259110632580/

1 This poem was composed by Salabega, a Muslim poet from the Mughal era: http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/jun2004/englishpdf/salabega.pdf

A version performed by guru Kelucharan Mohapatra, where the devotee can be seen offering namāz (customary Muslim prayer) before approaching Jagannātha: https://youtu.be/pVX8mEETsTw

2 I was surprised to find out that this ‘traditional’ headdress only came into fashion in the last century.

https://www.newindianexpress.com/magazine/2016/mar/05/His-Crowning-Story-900278.html

With many thanks to Sudheesh Bhasi and Meera Vijayan for their warmth and guidance.