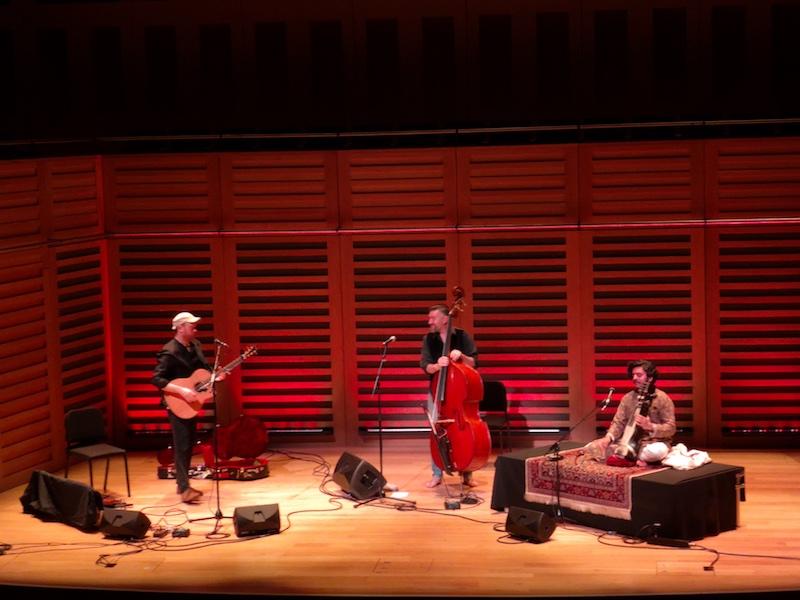

Yorkston Thorne Khan

Yorkston Thorne Khan

11 March 2020

Hall One, Kings Place, London

Reviewed by Ken Hunt

Photos: Santosh Das / Swing 51 Archives

Yorkston Thorne Khan are James Yorkston on nyckelharpa – a Swedish keyed fiddle –, 6-string guitar and vocals, Jon Thorne on double-bass, 6-string guitar and vocals, and Suhail Yusuf Khan on sarangi and vocals. The instrumental piece they opened their first set with had three bowed instruments. Their melding of Anglo-Scottish oral and written literary strands and northern Indian classical, semi-classical and folk traditions, with a sprinkle of new material at Kings Place, was nonpareil. Plus in the grand tradition of one branch of East meets West fusion, instrumentally the trio has an improvised heart.

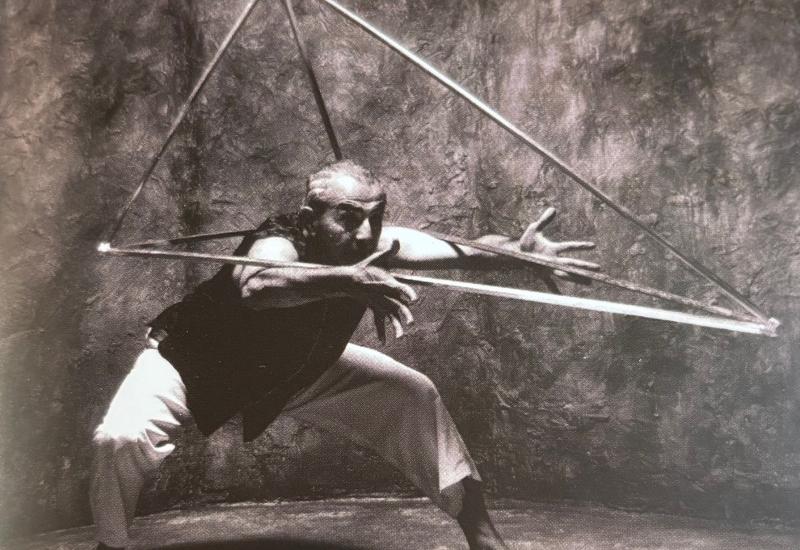

Aesthetically and commercially, since the 1960s the most successful early East-West fusion music has been refracted through prisms of highbrow art music or jazz. The collaborations between sitarist Ravi Shankar and violinist Yehudi Menuhin, beginning in 1967 with West Meets East in 1967 were, to be harsh, calculated. Menuhin sight-read his ‘pre-composed improvisations’. On the other hand, the trailblazing John Mayer-Joe Harriott double-quintet Indo-Jazz Fusions were flawed differently. The Harriott-led jazz contingent proved lazy about getting to grips with the subcontinent’s improvisatory principles that the Calcutta-born Mayer espoused. Arguably only with Shakti, led by Zakir Hussain and John McLaughlin – and the next incarnation Remember Shakti – was the dream fully realised. In 2008 my fuller history of Indo-Jazz took three articles, with sidebars and side-articles, over three consecutive issues of Jazzwise.

Since their recording debut in 2016 with Everything Scared, Yorkston Thorne Khan have shown how breakaway they are. They are unlike anything that went before. How they do that is simple. They blend north-western Indian and Anglo-Scottish literary traditions with a sprinkle of new material. Importantly, they sing. You might say their sung poetry is a definition of something old, something new, something borrowed and something blue. One paramount difference with them is that their masala blend balances. Their approach is, to go culinary, the opposite of those TV programmes in which the celeb chef ladles in ingredients in why? proportions or why add that at all? in ways to bewilder anyone familiar with that cuisine.

‘Twa (‘two’) Brothers’ and ‘Westlin Winds’, for example, blended, respectively, the Anglo-Scottish ballad tradition and bols (Hindustani rhythm syllables), and Sufi poetry and Robert Burns. Typifying the new (and blue) was Thorne’s ‘Song For Oddur’ from their third album Navarasa – Nine Emotions of 2020. Yorkston dedicated it. It was “for [jazz pianist-composer] McCoy Tyner who just passed away”. For it Thorne borrowed Yorkston’s guitar and sat down to sing it. Affectionate but with a blast of male bravado early on counterbalanced with recurring lines, “Love makes diamond from coal/And is the heart of all that is…” gained added poignancy.

It was an evening during which they sprung gorgeous musical surprises which took them well off the new album promotional path. They improvised instrumentally around themes. Their three-way interplay, with masses of eye contact, was sure and sharp, locked-in and hitting every change en route. Their closing number, ‘Sufi Song’ from their debut album, summoned the spirit of the 18th century C.E. religion-bridging Sufi mystic Mir Bulleh Shah Qadiri Shatari, described in J.R. Puri & T.R. Shangari’s Bulleh Shah (1986) as “the greatest Sufi poet of the Punjab”. It has grown into something mightier still since that 2017 album. The cry in Khan’s voice – both vocally and on or sarangi – was gut-wrenching.

Poetry and music have been inseparable since time immemorial. I like the element of risk, that all-important element of risk Yorkston Thorne Khan bring to their music. In my experience there’s nobody on the planet like them, let alone to compare with them. They are in a cleft stick, however. For conservative South Asian tastes Yorkston Thorne Khan may be too outré while most white European audiences might find their stylistic feat a bit too wayward. Stick with them. Attune. And go with their flow.