Hebridean Treasure

the Space @ Surgeons’ Hall

Edinburgh Fringe

15 August 2019

Reviewed by Sanjeevini Dutta

Summoning up the ‘cathedrals of sky, sea and land’ in the restricted space of a black box was the challenge for dancer Kirsten Newell and her team of musicians and narrators; but they succeeded admirably. In an hour-long performance, the artists conjured up the landscape of the Scottish Isles and the deep connection of their inhabitants with the rhythms of nature. The writer John Philip Newell is at the forefront of a movement that promotes and celebrates ‘Celtic consciousness’, a form of Christianity that honours earlier pagan beliefs in the sanctity of nature.

The vocalist Mischa Macpherson opens with an evocative solo as the three narrators and dancer line up one behind the other. The singer is backed by the fiddle (Charlie Stewart and Cameron Newell), the harmonium (Alistair Iain Paterson) and percussionist (Cormac Byrne), and also Indian vocalist Ankna Arockiam. The music is pitch perfect throughout and blends beautifully with dance and movement. The opening lines that find ‘God’ in every element set the tone, although Kirsten’s namaskara, touching of mother Earth to pay respect, profoundly chimes with the spirituality of the piece and makes the explicit statements less essential.

The body of the performance consists of Gaelic songs and incantations from the Carmina Gadelica, collected by Alexander Carmichael in the late nineteenth century. One of the stand-out moments is the dance of the ‘Sister Moon and Brother Son’, where the male and female characteristics are etched with fine movement and expression. The use of hand gestures (mudras) is particularly effective in this dance, as in creating the array of birds and animals that stud the dances. The narrative comes alive with Alison Newell’s warm and empathetic tone conveying the imprint of the divine in every newborn, as she performs the ritual blessing to the newborn.

In the second act we learn about the suppression of the Celtic spirit under the Reformation and the Calvinist ‘prudery’ that frowned upon music and dance. The final blow to local culture is dealt by the Highland clearances of the nineteenth century, wherein the crofters were driven off their lands for commercial sheep farming, forcing them to migrate to Canada and the United States. This chapter is narrated and conveyed by the dancer in sharp, cutting movements.

The final section is the journey of death and rebirth as the big sleep overcomes the dancer and she lies down. The new shoots push through the ground…

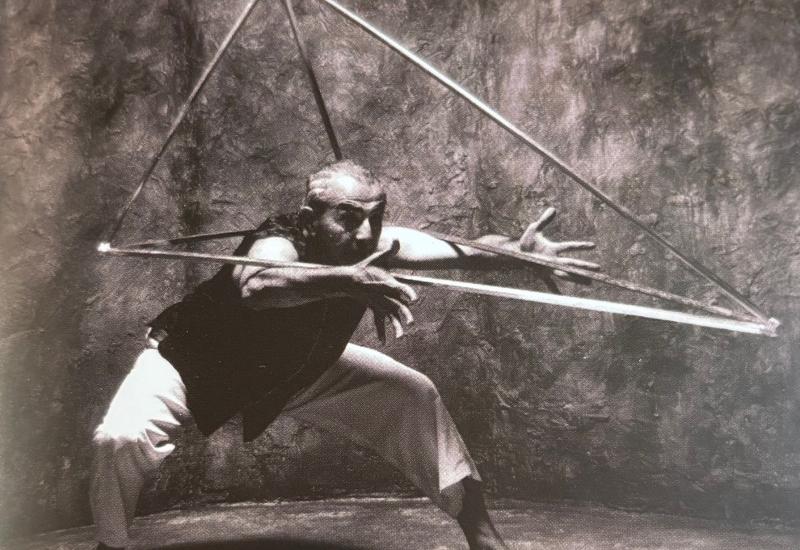

The show creates a satisfying viewing experience and has a lot to commend it. There is a seamless quality between music, movement and narration. Kirsten Newell, trained in bharatanatyam both in Edinburgh and at the premier institution Kalakshetra in Chennai, India, grows and blossoms as the piece progresses. Her light frame, which has great suppleness, is matched by the strength borne of her classical training and her engaging presence captures and holds our attention. She has been working with choreographers Shane Shambhu, who also directs Hebridean Treasures, and with Seeta Patel, and no doubt her performance could be pushed even further when she can use space dramatically on a full stage.

The performance has a unique quality in that bharatanatyam becomes a universal form and yet the show retains a sense of place. The Gaelic connections of music and episodes from the lives of people in the Highlands and Islands will bring joy to the people of Scotland and beyond and we would love to see it played in every town and village to celebrate the Celtic spirit.

Response from Magdalen Gorringe

Hebridean Treasure is a moving meditation on Celtic spirituality – both dance and poem; lament and love song; prayer and blessing. Watching the piece I felt that no dance vocabulary could be more apt for this work than bharatanatyam which springs from sadir, a dance form, which like Celtic Christianity, recognised and rejoiced in the sacred within the sensual; the omnipresence of God, and the holiness of the dark dirt of earth. Like Celtic Christianity, sadir’s sensuality was rejected and crushed – like Celtic Christianity, it is bubbling irrepressibly forth again, not least in the dance in this piece, embodied with commitment, conviction and charisma by Kirsten Newell.

Remembering the history of the Scots crofters, dispossessed of their land to make way for more profitable sheep, the piece regrets how some then repeated this same cycle of violence by in their turn dispossessing others in Canada and North America. Others broke this cycle, turning their experience of suffering to feed their compassion and passion for justice. The spirit of God, the piece tells us, is within those who hunger for justice, for the true peace of the running wave. Though crushed, this spirit will rise, though hidden, this spirit remains. In these times of extremism and hate, where children are torn from their parents, and courageous souls are imprisoned for refusing to be blind to suffering – this was a message I needed and wanted to hear. In this sense, this is truly a piece for our times.