The Changing Face of Classical Dance in India

Scholar, historian, dance critic and commentator Leela Venkataraman has been writing about dance in India for more than thirty years, her distinguished reputation built on her possession of that rare quality, dispassionate observation. Her publications include Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition (with photographer Avinash Pasricha), A Dancing Phenomenon – Birju Maharaj and, most recently, Indian Classical Dance – the Renaissance and Beyond. Pulse is honoured to carry this article.

How does one define and decipher creativity in Indian classical dance forms wherein one uses a symbolic language to re-invoke the perennial through the distinctiveness of time and space?

Thinking back on nearly forty years of watching and writing about the dance, there are two episodes that stand out in memory like beacon moments of what one could only think of as being totally out of the ordinary and representing what I perceive as artistic creativity. One happened when watching a kutiyattam (or koodiyattam, the dramatised dance form from Kerala) presentation by the late Guru Ammanoor Madhava Chakyar (1917‒2008), who was by then all of a feeble 80+, being escorted on to the stage with two disciples supporting him on either side. Appearing slowly from the wings, he came to the centre of the performance space at the National School of Drama’s Abhimanch auditorium (Delhi), with the disciples helping him settle down on an 18inch-high stool. Moments later, after an unblinking stare at the flaming torch held before him for prolonged seconds, he remained as if in deep contemplation. Most of the packed, expectant hall was thinking in terms of a demonstration of mudras with some strong facial expressions. But to their wonderment, after about ten minutes, galvanised by some inner force, in one purposeful movement the guru suddenly stood up on the stool and began to demonstrate the scene of Ravana lifting Mount Kailash, the home of Shiva and Parvati. His eyes spoke. One downward gaze with eyes wide open and the pupils seeming to go down endlessly, and the audience saw in the mind’s eye a deep gorge with a valley below stretching for miles.

The eyes were then raised slowly upwards, the pupils climbing higher and higher till they disappeared into the upper eyelids and the audience got an awesome feel of the towering Himalayas, their peak reaching for the skies. Ravana lifting the mountain and juggling with it like a ball was performed and what followed for about twenty minutes is, after all these years, still etched on my mind. How long could the slender frame stand such frenetic movement without toppling off the stool? Every member of the audience at the National School of Drama sitting on edge wondered if the final moments were being witnessed of a legendary performer who, with a powerhouse of inner energy, was creating history – through a minimal movement-language with an ageing body and just a stool top for performance space. What Ammanoor Madhava Chakyar had communicated through a spartan vocabulary of gestures and movement was the consciousness of a whole ecology – the largeness of Kailasa – an abode of the Gods! I thought of Dr Kapila Vatsyayan’s sentence in an essay in Metaphors of the Indian Arts: “‛Creativity’ is the sudden luminous spark which makes the familiar unfamiliar, or unfamiliar familiar each time giving it a new significance.”

“…the person incapable of contemplation cannot become a great artist…”

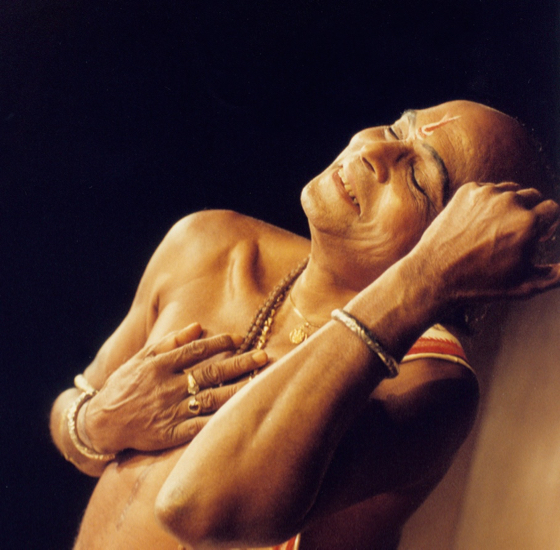

Kapila Venu | Image: Courtesy the artist

Our traditional dances are concerned with an interpretation of life. Recapturing an incident through retrospective reflection, with distance of time lending a new vision through detachment of mind and restraint, presupposes a mental cultivation and a preparedness, making art creativity more an intellectual exercise, even in dance, which is such a physical art; which is why Ananda Coomaraswamy, the great commentator on Indian art, maintained that the person incapable of contemplation cannot become a great artist, though he may well be a skilful workman – as many efficient dancers prove to be when unable to go beyond very correct technique.

Where does creativity rest and what transforms a dormant urge into a vital force? One can take the instance of Valmiki in a turmoil of emotions roaming within the forest. But it was watching the hunter’s arrow killing the krauncha bird (crane) followed by the wailing of its mate that suddenly triggered a storm of feelings, making poetry pour out in the form of the epic Ramayana. This experience was like clarity emerging after inexplicable mysticism. The late scholar K. Chandrasekharan in his writings on creativity explains this through an example. He describes it as going through a fog without knowing one’s destination till one suddenly discovers oneself standing before one’s own house! It is the sudden expansion of the consciousness in the supra-personal world of man.

Yet another unforgettable instance was when watching the late great Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra (1926‒2004) in a class teaching a bunch of students who were told to demonstrate a bhramari 1(pirouette), maintaining the body in the half-seated chauka 2 position. The onlooker was predictably treated to varying degrees of proficiency till the guru got up from his place in front of the pakhawaj and himself demonstrated the movement. For me, it seemed as if the entire room was revolving with his body as he executed a slow and immaculate bhramari. Here was the evolved power in one movement extending into space far beyond the physical limits of the dancer’s body. This ability to transcend the physicality of the body suggesting through symbolic language a larger-than-life world outside of oneself is what creativity is all about in Indian classical dances.

For me, the greatest challenge as a critic has been to acquire the ability to look at each performance separately in isolation, without trying to mentally compare or connect it with what one has seen of that genre before. One cannot go to a performance with preconceived notions of what one wants to see. One suddenly finds an unexpected something lifting a recital above the ordinary, investing it with a certain freshness. Ill-conditioned ungainly bodies, barely able to move due to their being overweight or for other reasons making for a total lack of visual aesthetics, could still hold the viewer’s attention with some other redeeming feature, like communicating emotions and ideas in a manner so gripping that poor physicality ceases to matter.

Kelucharan Mohapatra | Image: Courtesy Srjan

In this connection, I cannot help but recollect a recent experience in Pune when I was treated to an enactment of Marga Natya, a reconstruction of ancient nritta (abstract dance) and natya (the dramatic aspect) as envisaged by Bharata Muni in the Natya Shastra, the result of seventeen years of undiluted research and contemplation by Piyal Bhattacharya (alumnus of the Kerala Kalamandalam and who heads the Chidakash Kalalay Centre of Art and Divinity, transmitting art in the time-honoured Gurukul pattern, in a suburb of Kolkata). Few in the audience knew what to expect. The ‘Chitra Poorva Ranga’ of the Natya Shastra, with sangeeta (music) created by musicians seated behind a curtain playing unfamiliar instruments, resembling what Bharata mentions as the ‘Ashravana Vidhi’ was followed by the entrance of the skimpily-clad dancers looking like creatures stepping out from a second-century temple sculpture, in the ‘Asarita Vardhamana Vidhi’, with gyrating movements, creating a shock at first as if there were some kind of burlesque theatre in the offing; and finally came the ‘Uparupaka Bhanaka’ with the entry of the Sutradhar (narrator), whose extraordinary histrionic power with the Sanskrit soliloquising soon had the gathering eating out of the hands of the performers. The Sutradhar – representing omniscient consciousness with the one-stringed veena in hand – endorsed all to banish agnan (ignorance) through prajnana (wisdom). The entire audience was lost in an evoked world, which had opened spaces of experience to us that we never knew existed, through great art. I realised that a body movement by itself is nothing for it is the mover’s intention which imparts to it a meaning.

Here the story was about the retelling of the tattva or ‘Reality of the Universe’ and contrary to what one imagined, the kati (waist to hip girdle area) movements and the pulsation gradually built up to an elevating feeling. I rate it as one of the most extraordinary experiences as an art lover, for all my long-held ideas collapsed after being treated to such an uplifting experience. The thundering applause from a captivated audience spoke volumes.

Today’s constant obsession with the beautiful body and costuming for the dancer has made it more difficult for the dancer to obliterate the persona and become just the dance. The less physically-endowed dancer has been rendered almost dysfunctional. One is reminded of Achhan Maharaj, the father of Birju Maharaj, whose pot belly and ordinary physique ceased to exist when he danced. A foreign visitor in the Lucknow Nawab’s court had problems in imagining the very plain man in front of him as the intended dancer for the evening reception till he saw him taking the slipping end of the top cloth draped over his torso and putting it back on his shoulder in one gesture. That one movement had enough grace and beauty to convince him that he was indeed in front of a born dancer. Balasaraswati’s bewitching dance poured from the inner dancer who neither cared for nor depended on physical features or even aspects like stage aesthetics.

I have seen BIrju Maharaj hold an audience at the Kamani spellbound with just a performance of Thata3 for an entire performance. One cannot forget the kind of artistic experience created by the late Kelucharan Mohapatra. One experiences a sense of nostalgia that the age for that kind of genius seems to be passing and we will see very little of that kind of creativity. Many of my favourites were among the generation now lost to us. The scenario today comes with its own compulsions and yardsticks. Now one looks for the ability to communicate with a cosmopolitan audience, the aesthetics of presentation, the covering of stage space effectively, designing a recital covering all important elements within the allotted time span, and instead of improvisation, the accent is on what is loosely referred to as choreography.

While watching a performance today, where does one put technique and a well-honed body? Grammar and technique are very important and certainly give to movement a finish. Correct technique is the starting-point of a long journey in dance expression, like the knowledge of language and grammar if one needs to write poetry. If one does not have even this basic requirement, what is built on a faulty inadequate foundation will also lack perfection. Bodies badly held, insufficient attention paid to the central stances on which a dance form is anchored, like a bharatanatyam araimandi4, an odissi chauka and tribhangi5, the mohiniattam araimandi; Manipuri, where the dancer mastering the light-footed dipping and raising of body constantly weaves a figure of eight; or a kathak dancer whose knees must be held straight while doing a tatkar6 – all these are important. But once the technique has been mastered, what is more important is what the dancer has to say with it.

Without involvement, even the best technique will be dry. Sometimes the body seems to be moving without the mind and heart of the dancer involved. One sees rhythmic sequences being presented by an automaton. One comes across this aspect very often, particularly when the overwhelming nritta razzmatazz creates a virtuosity-replete performance, the dancers looking for all the world like puppets who have been keyed to move.

Even pure rhythm cannot be just an arithmetical exercise. As Pandit Birju Maharaj says, “Even in a hand tracing a ‘Tat tat thai’ the abstract movement, unless in perfect coordination with mind and spirit, will become empty geometry with nothing to say.” His demonstrations in class trying to impress upon the disciple this vital aspect of mind/body connection are most revealing. He asked a student: “What is this hand doing? Is it not your hand, part of your body? Do not treat it as an unconnected something outside of you. Treat it with love and show the concern that you are behind the movement.” So too, the element of sahitya (literary content), when incorporated, needs to have proper representation in the dancer’s interpretation.

The language of word and movement needs to conjure up a picture that has immediate access to our hearts. So technique and physical perfection can be an instrument of dance and not its fulfilment. Kalidasa maintained “Vakarthaaviva sampruktau vak artha pratipattaye”7 wherein word, its meaning, sound and sense have to unite perfectly. When all these come together in a perfect union, the persona of the dancer ceases to exist in itself. The dancer then becomes the dance. To erase the feel of the dancer’s strong individual self is difficult in a performance. I have always been impressed by how Leela Samson, an individual with strong ideas, ceases to exist as an entity when she performs, with the dance completely taking over. This eradication of the self, or burning up of the ego, I find does not come easily to dancers of today, brought up to believe that the individual in the persona is important. In the case of many of the star dancers, the persistent feeling of so-and-so dancing never goes away.

I have a penchant for dance that has an underpinning of serenity, and performances that have the sense of musicality and poetic quality are for me special. These qualities seem to unveil the invisible links of a cosmic consciousness wherein contrary and remote aspects seem to cohere in a sense of completeness.

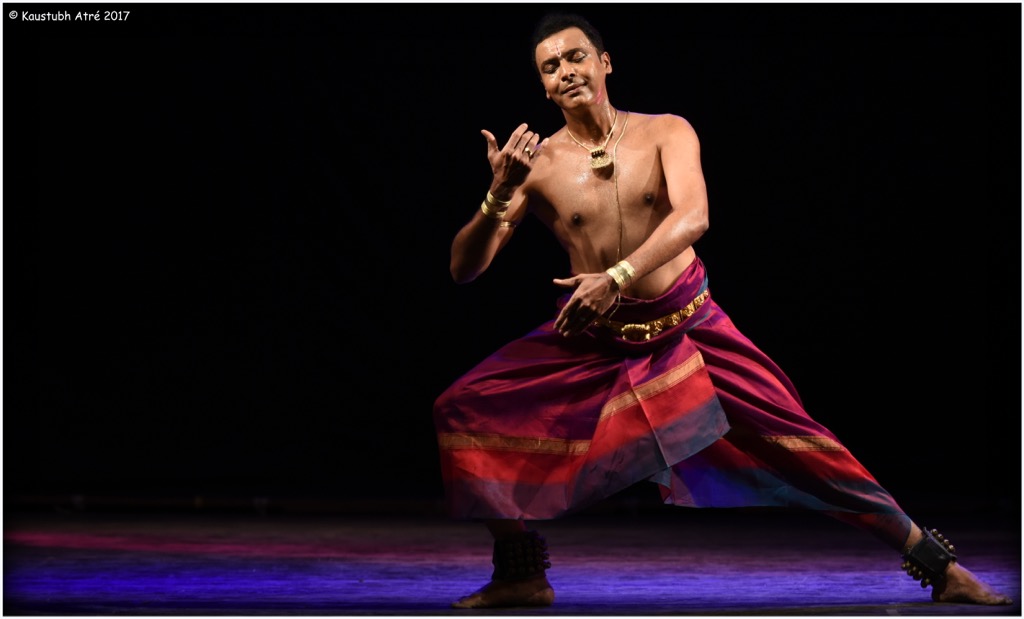

Vaibhav Arekar | Image credit: Kaustubh Atré

The ability to improvise on stage while a line is being sung is more or less a dying art. There are a handful of dancers whose abhinaya ability one admires, like Braga Bessel and Lakshmi Viswanathan, both very different types of dancers. The first is a true disciple of Kalanidhi Narayanan who concentrated on mukhabhinaya9 and who was responsible for giving back to abhinaya a place it had almost lost in the post-devadasi period. Lakshmi’s sophisticated approach, aside from what she obtained from the gurus like Ellappa Pillai under whom she trained, is a style shaped by the musicality she acquires from her family background, with her scholarship giving it a certain character that delights in angikabhinaya.10

A dancer who also stands very high in abhinaya presentation is Swapnasundari, the kuchipudi/vilasini natyam specialist, who has studied under the Andhra devadasis to master a very wide repertoire extolling the sringar (sensuous love) aspect. Padams (lyrical songs) and javalis (lighter, livelier songs) in her dance can extend into hour-long compositions, so endless are the elaborations her interpretative skills can conceive.

Her portrayal of Shoorphanaka (sister of Ravana, her name means ‘sharp, long nails’) on the occasion of the Ramayana-based Natya Kala Conference at Sri Krishna Gana Sabha in Chennai brought to the fore a rare excellence. Never had I witnessed the enormity of Shoorphanaka’s physical and emotional get-up brought out so tellingly in dance. The dancer’s netrabhinaya11 as the demon’s eyes summed up the handsome figures of Rama and of Lakshmana, losing her heart to one and then the other too, is still fresh in many minds. As a trained vocalist, Swapna’s singing adds a special dimension to her presentations. The other dancer whose abhinaya depth takes on an exceptional quality, drawing on nothing but the limitless expertise in pure classicism, is Guru A. Lakshman whose interpretation of items like the Usseni Swarajati has few equals. He makes one of the best nayikas of any denomination that I have seen. These artists could sustain a whole programme on abhinaya alone, without any nritta relief.

Among the younger dancers of today, a male dancer whose performances I look forward to is bharatanatyam artist Vaibhav Arekar based in Pune. Endowed with a fertile creative imagination that can take on any theme and build on it, giving even margam items he presents an ever fresh feel, Vaibhav commands excellent technique, rare communication skills, a fine presence without an overwhelming sense of self, and a sensitivity to poetry and music. Having studied theatre, he is able to bring to the dance a subtle dramatic sensibility that heightens viewer interest without seeming to be violently unorthodox. Dancing to a Poochi Srinivasa Iyengar varnam (a technical piece with expressive sections), Dani korikenu niraverchutakide tagina samayamu raa Tamarasaaksha set to a rare Misra Jhampa tala, which, at least in the recent past, has never been presented, I was struck by his interpretation of the lovelorn nayika (female protagonist), entreating her friend to convey her message of love to Lord Vishnu, pleading that he answer her call of love at once. What is set in the very traditional varnam mould in Vaibhav’s dance, visualisation was totally without the much-rendered hackneyed feel. Rarely does one see a male dancer so unselfconsciously present nayika bhav (expression) with such conviction. And what is more, the dancer, without any part of the rendition being effeminate, transcended gender consciousness, his male presence never disrupting the portrayal. As for the nritta (abstract) interludes, they had originality in the grouping even while within the bharatanatyam adavu (movement unit) vocabulary. Whether presenting dance theatre based on Tagore’s children’s poetry, the tragic parts so moving that there was not a dry eye in the auditorium, or a presentation based on the river Narmada, or on compositions of the seventeenth-century Marathi poet Tukaram, or humour ‒ which is so rarely treated in our dance ‒ there is a feel of visceral involvement in his dance. His dance, based on a very traditional movement idiom, bristles with a sense of immediacy with time, past and present, strung into continuity.

Nina Prasad, the Mohiniattam dancer, is another artist whose performances, suffused with the typical Kerala magic, never compromise with the slow haunting quality of movement in her dance style. Well-selected themes, and the constant musical backdrop provided by her vocalist Changanasseri Madhavan Nampoothiri with whom she works constantly, give her performances an edge.

A dancer who never tries anything beyond what her Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra taught, Sujata Mohapatra’s odissi, as the epitome of what this dance should be, never fails to charm audiences. Apart from being able to visualise the well-known repertoire in recitals, the need to fashion new compositions poses challenges. Many dancers of today commissioned to present new packages are engaged in this task in varying degrees and have met with success too. One dancer in her 30s who has excelled in the rare kutiyattam form is Kapila, the disciple of Ammanoor Madhava Chakyar, who as a solo woman performs narratives fashioned and designed for her by her gurus with father G. Venu helping. While she calls herself Kapila Nangiar, she does not come from the female tradition of these performers in temples. These female performers have their own vocabulary of hastas (hand gestures) and a repertoire which is special to Nangiar Koothu. Under Guru Ammanoor Madhava Chakyar in Irinjalakuda, Kapila was trained in kutiyattam and showed herself to be a fine talent. Apart from ‘Subhadra Dhananjayan’ and other typical Krishna-based items, Kapila’s performances in segments of ‘Shakuntalam’ as Shakuntala and in the narrative of Sita being left to live in the forest by Lakshmana on the orders of Rama are done with great power and control. She is certainly one of the highly creative figures in this art form!

A fast-rising bharatanatyam dancer, Meenakshi Srinivasan, has composed Sita’s Agni Pravesham, which I consider as one of the extremely well-conceived items. First is the selection of a sequence which has tremendous dramatic potential, comprising in a way a whole philosophy on the treatment meted out to women in a patriarchal society. The selected Sanskrit verses from Valmiki Ramayanam translated into Tamil by a scholar and the nuanced music composed by Hariprasad provide the right foundation. And Meenakshi’s interpretation preserves the poignancy of the episode by not exaggerating and without any didactic padding, allowing the moment to speak for itself. The concluding circumambulation of Sita by Agni, who tells Rama that his flames cannot ever touch or purify someone as blemishless as Sita, says it all. The segment from an ancient epic has a message as relevant for women’s empowerment today as then. And this is the way to underline the eternal present in myth and epic. This is the direction in which classical dance should spread.

1. Bhramari – pirouettes, also called ghera in odissi; both clockwise and anti-clockwise are common. This can be with one leg anchored on the floor while the other is in the air as the circle is taken.

2. Chauka – half-seated plié with weight balanced equally on both feet and the two feet maintaining a distance so as to form a square geometrical motif ; one of the basic stances in odissi.

3. Thata – reposeful start of a traditional kathak performance, with minimal movement as the dancer allows herself to absorb the musical refrain (lehra), preparing the body for the strenuous dance to follow.

4. Araimandi – the half-seated plié which is the main stance of bharatanatyam, with the two feet placed closer to form a triangular motif.

5.Tribhangi – one of the main stances along with the chauka in odissi where a sharp deflection of the hip from the horizontal kati sutra (the section between waist and hip), an opposite deflection of the torso and the head deflecting to the same side as the hip produces the three bend or tribhangi, a very graceful posture.

6. Footwork in kathak.

7. Kalidas in Kumarasambhavam showing how closely Shiva and Parvati complement each other as a couple.

8. “Osai olimellam aanai neeye...” Tirunavukkarasu, one of the celebrated Nayanmars living in the seventh century, sang thus of his perception of Shiva in mystic poetry.

9. Facial expressions used to convey meanings and emotions.

10. Bodily movement (without face) communicating feelings through its stances and attitudes.

11.Conveying emotions and meanings through eye movements.