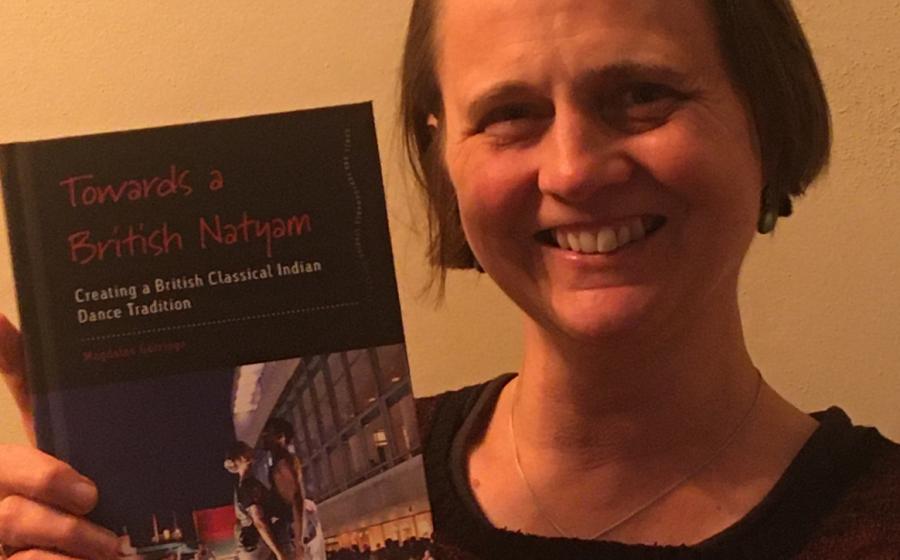

Towards a British Natyam -Magdalen Gorringe

Towards a British Natyam

Magdalen Gorringe

Published by Berghahn, 2025

Reviewed by Sanjeevini Dutta

The timing of Magdalen Gorringe’s book Towards a British Natyam happily coincides with the uplift South Asian dance received in the last funding round of the Arts Council (2023-2026). It is almost as if the weight of thinking around the next steps for the dance form began to shift the needle as the author was gathering data for her PhD at Roehampton University on which the book is based.

The central question that the author poses is why Indian classical forms have not found the space in the British dance field or in the audiences’ hearts in sixty years whereas two other foreign imports, namely ballet (with Russian and French antecedents) which came in 1930’s and Euro-American contemporary dance which entered Britain from the States in early seventies were firmly established as ‘British dance forms’ within a decade. Training schools were established and theatre spaces made available for presenting ballet and later contemporary dance. But will Indian classical dance ever fit into the national cultural canon (think Nutcracker or Swan Lake occupying the same space as a dance based on the Ramayana or Mahabharata)?

Gorringe examines the health and position of ‘classical Indian dance', the term deployed when referring to the dance forms, and ‘South Asian dance’ when talking about the sector, through three variables: learning, livelihood and legitimacy. These three factors operate in a circular way.

The training in classical dance mainly takes place at weekly classes, supplemented by holiday intensives and / or short courses in India. The examination system of the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing (ISTD), facilitated by Akademi under the directorship of Mira Kaushik, has done much to raise and standardise teaching. However, there are no professional training institutions. Therefore the question remains of how we expect the aspirant to a dance career to reach the standard required of a professional? Although professional courses were set up in the past they failed to recruit, since lack of opportunities to earn a livelihood seriously undermines the desire for a full-time career, a chicken and egg situation.

For families of South Asian heritage ‘bharatanatyam is not just a dance, but a whole package of Indian culture and identity’. However, if these dance forms were freely available and not targeted at the community alone, would we have a different outcome? Gorringe postulates that government policies of ‘ethnic’ arts and ‘multiculturalism’ further ghettoise these dance forms suggesting that their relevance is to the Asian community alone. Pressing this concept further the author will propose in her conclusion the idea of ‘pluriversality’, the idea that no one cultural view can claim the badge of being ‘universal’.

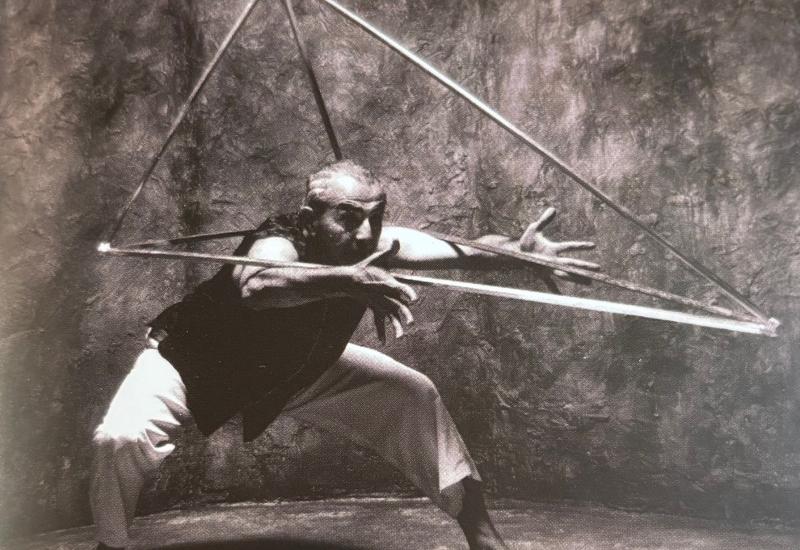

‘Non-dominant dance styles struggle to stake their space within a field governed by a dance form…that favours a different aesthetic, a different doxa, a different habitus’. The technical term ‘habitus’ refers to ‘an embodied inclination…of social structures and history carried in individual’ extended by the author to include physical aspects such as muscle memory and the ways of moving that a dancer acquires over years of training, such as the ability to stay in an araimandi (the turnout at hip and knee). This skill may not be of use when auditioning for a dance company needing some contemporary dance experience. The skills of a classically Indian trained dancer such as complex play of rhythmic patterns, sharp and precise lines of bharatanatyam adavu and use of abhinaya have not yet found their place on the British stage. For the skills acquired by classically trained dancers to be harnessed in the professional field of British dance, it has had to find ways of combining with or integrating into the values of Euro-American contemporary dance.

At the root of the issue is the uphill task of legitimising an aesthetic tradition that draws from a non-European culture. Quoting sociologist Quijano, ‘European culture became a universal cultural model’. The role of colonisation in perpetuating this belief needs to be recognised, as it is often unconscious.

Returning to the Arts Council last funding round the good news was that the allocation of funds to South Asian dance had a seventy per cent increase with the number of NPOs (National Portfolio Organisations) doubling and for the first time three new companies formed that ‘aim to explore and sustain a dance style’, that can offer longer-term employment to dancers.

Magdalen Gorringe has a unique position as both a practitioner and a scholar. Her insider’s knowledge and her passionate advocacy is underpinned by solid research, reaching into anthropology, philosophy and even sports science. Despite the theoretical scaffolding and numerous citations, her writing maintains an informal, intimate style, starting a chapter with her attendance at a performance and after much theorising taking the reader back into the show’s conclusion.

The author’s vision of British society embracing a ‘pluriversal cannon’ where several aesthetic and cultural visions can co-exist may be utopian, but she makes a persuasive case in the on-going debate of the nation's self-identity.

A reviewer cannot do justice to the extent and depth of the book. There are several fascinating observations: on dance competitions; on the peculiar dual-profession dancer, so common in the South Asian context, and debates around what makes a ‘professional’ dancer.

The book’s insights will be invaluable to dancers struggling to establish their dance form’s legitimacy, so that they are not constantly apologising for their dance being different from the Euro-American contemporary dance, the default mode in the UK. Armed with these concepts and arguments they could make a more confident approach to venues, promoters and funders.