Delight and Disquiet – Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875-6

Splendours of the Subcontinent consists of two linked displays of objects and works on paper acquired by the Crown, largely as gifts from Indian Rulers and officials of the East India Company. It will prompt a mixture of emotions ranging from delight to uncomfortable fascination.

What started as a commercial venture by the Company became eventually a full political engagement by the British state in an imperial enterprise giving the monarchy a crucial symbolic role. As with most gifts in such a situation the givers were as obliged to give as the recipients were to receive. We see the interaction with and the impact of Mughal and sub-Mughal court culture upon the British Crown, a story of power and seduction that certainly enchanted some of those involved. In 1815 with the Pavilion at Brighton the Prince Regent seemingly made a version of Lucknow on the South coast. Perhaps more worthily but no less enthusiastically Queen Victoria created the ornate Durbar Room at Osborne House in 1891, a tribute to the design and style of her newish Empire.

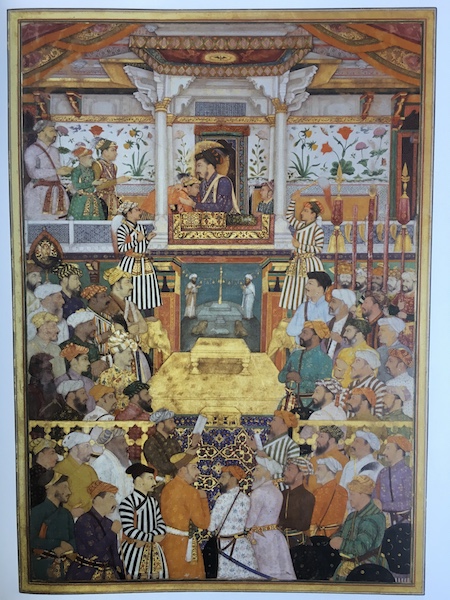

The most impressive section of the exhibition is devoted to examples from astounding holdings in the Royal Collection of miniatures and manuscripts made in India from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The connoisseurship of painting and calligraphy was a feature of imperial and princely culture in the subcontinent as much if not more than the equivalent taste for collecting of Western art among European rulers. It is not surprising that these treasures should have been offered to the Crown in an acknowledgement of new realities of power. Notable is the a selection from of the wonderfully varied series miniatures which were compiled into the Padshahnama of Shah Jahan, a set of supremely complex representations of key events in his reign by a number of highly talented painters: a remarkable if not unique example of image preceding text. These have supreme aesthetic and historical importance and it would not be an exaggeration to compare them with the Bayeux Tapestry or Rubens’s cycle of the Life of Maria De Medici. The actualisation of events required vivid portraits of the various participants so it is very interesting to see these alongside the albums of portrait miniatures and also of types (such as yogis and courtesans) which informed the compilation of complex paintings. Shah Jahan, like his father Jahangir, was an extraordinarily engaged patron, personally overseeing the work of his painters. The immense visual power of Mughal culture in the assimilation of the miniature style is evident in illustrations of the late eighteenth century Hindu narrative of Prahlada from the Bhagavata Purana.

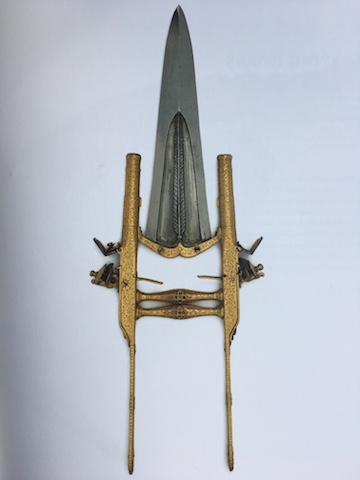

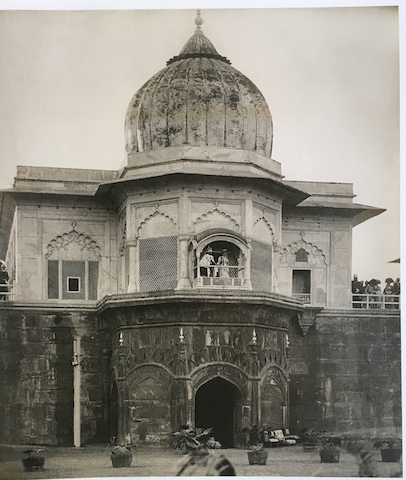

The other part of the display, devoted to the gifts received by the Prince of Wales on his visit to India in 1875/6 shortly before his mother assumed the title of Empress of India also demonstrate the prevalence of Mughal taste, albeit in a rather debased form. This comprehends a splendid selection of gaudy and ingenious ornaments and weapons and such-like knickknacks which were the quintessential products of a fervid gift giving culture. Although you may not get gold and jewels, anyone who has been given presents from or indeed been shopping in the subcontinent, will be familiar with the highly wrought look, and if you like it you are in company with the Prince Regent, Queen Victoria, Edward VII and Queen Mary. In the catalogue there is a photograph that points up the problematic nature of British Imperial experience. George V and Queen Mary, crowned and robed for the 1911 Delhi Durbar, appear rather squashed on the balcony of the Red Fort, acting out the Jharokaha Darshan, the public audience ceremony of the Padshah, the Mughal Emperor, but there are no crowds below – just potted palms and some casually placed chairs.

This exhibition, supported by two excellent scholarly catalogues, is immensely rewarding, for the outstanding beauty of the earlier calligraphy, manuscripts and miniature painting, as well as for the light it shines upon a troubling and complex history marked by other famous, indeed notorious, Royal acquisitions, such as the Koh-i-Noor diamond or the regalia of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875-6 continues at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, until 14 October 2018.

Catalogues:

Kajal Meghani, Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875-6 (Royal Collection Trust, 2018)

Emily Hannam, Eastern Encounters: Four Centuries of Paintings and Manuscripts from the Indian Subcontinent (Royal Collection Trust, 2018)

Events:

There are performances, short talks and a study day taking place in connection with the exhibition. Akademi is presenting a performance on Thursday 12 July at 6.30 pm.