Dakshina

Elena Catalano and Kamala Devam

Presented by Akademi

Friday 20 April 2018

Rich Mix, London

Reviewed by Donald Hutera

Solo performances reveal a dancer’s style and skills, the manifold ways in which stage space is claimed and what level of rapport can be established with an audience. Produced by Akademi, this particular evening provided ample and rewarding insights into the highly contrasting ability of two classical dance artists to accomplish all of the above.

The programme’s umbrella title is Sanskrit for any form of payment offered in return for education, training or guidance. As the performers themselves indicated in the first of several short, informative and winning film introductions to their various dances, the word neatly encapsulates Elena Catalano and Kamala Devam’s joint offering to the gods and gurus who’ve shaped and influenced their respective artistic progress.

Catalano was on first with a pair of odissi solos, both choreographed by Kelucharan Mohapatra. The initial work was pure dance and the follow-up a narrative-based demonstration of abhinaya, an order to which Devam also subscribed.

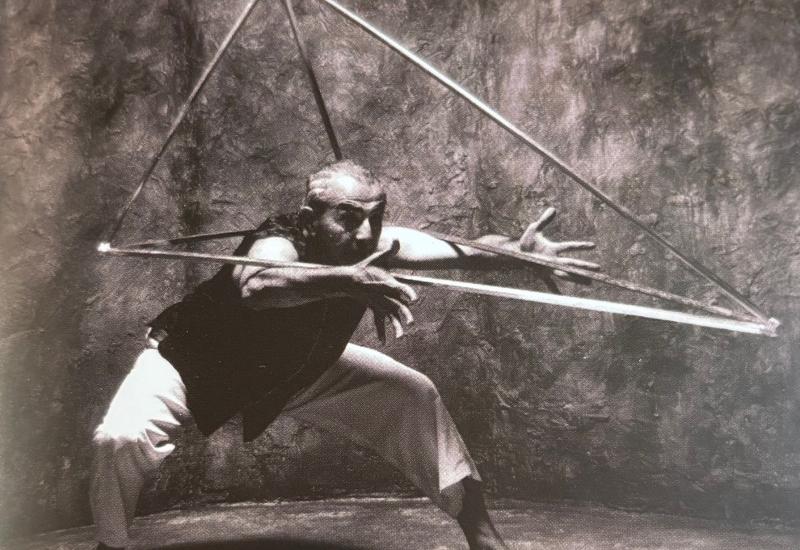

The curtain-raiser, Hansadwani, got off to a beautiful start thanks to the eloquent, melismatic vocalising of Deepa Nair Rasiya, who was subsequently closely supported by Parvati Rajamani (manjira), Gurdain Rayatt (mardala) and May Robertson (violin). Catalano soon materialised. Physically petite, she has an alert, magnetising stage presence. Her dancing is bright, quick and richly detailed, and marked by a seemingly easy, yet potent, charm. In her can be discerned a double geometry – corporeal, yes, but also that of the stage space containing her. She operated on two planes, as if upper and lower body were split at the waist. Expressions and gestures – come hither eyes, head tilts, twisting wrists and twining arms, or an alternating, ladder-like and upward climb of the fingers – were balanced by heel-ball steps, emphatic stamps or the subtle surety with which a foot spiralled up behind a knee. Extremely pleasing it all was, too.

On film Catalano remarked that this solo makes her happy. I felt similarly about both it and her second solo, Patacharide, which depicts an encounter between Radha and Krishna. Here Catalano exuded a stylisation both seductive and divine, but imbued with a humanising sense of character. Her Radha was serene, direct and tolerant of Krishna’s mischief-making, especially during a visit with friends to a watering hole at which Catalano portrayed him nabbing and flinging about their saris. Such pretty swimming, and a delicate, precision stealth.

After the interval it was Devam’s turn to shine. While Catalona tends to draw us in, Devam reaches out. It took a bit of time for me to adjust to her more expansive use of the stage, in keeping with her longer limbs, rangier physique and the broader strokes of her brand of bharatanatyam. In Natyanjali, a tribute to the deities choreographed by VP Dhananjayan in 1968, she was at her most extrovert. I enjoyed Devam’s bounding generosity, but preferred the abhinaya piece Theruvil Varano. Here she expressed an adolescent’s ardour for Shiva, complete with blushes, sighs and pouts. This well-observed characterisation felt fresh, witty and thoroughly inhabited. Musical support came from Pushkala Gopal (nattuvangram), Jalatharan Sithamparanathan (violin), Senthuran Premakumar (percussion) and Vamshikrishna Vishnudas’ strong vocals.

There was neither vocalist nor violinist for Devam’s self-choreographed finale Jati-Swara-Leela, a semi-improvised display of virtuosity featuring dramatic rhythmic accompaniment by cellist Danny Keane. Devam, excited and magisterial, responded to his instrument’s deep throbs and hi-pitched scrapes with a whirligig vigour and speed. Rubbing her palms she used her feet to produce friction with the floor, carved space with her arms and sprang undulantly and exultantly into the air. It was, in a word, exhilarating.