Aruna Sairam-Darbar Festival

Barbican Centre, London

17th October 2024

Reviewed by Ken Hunt

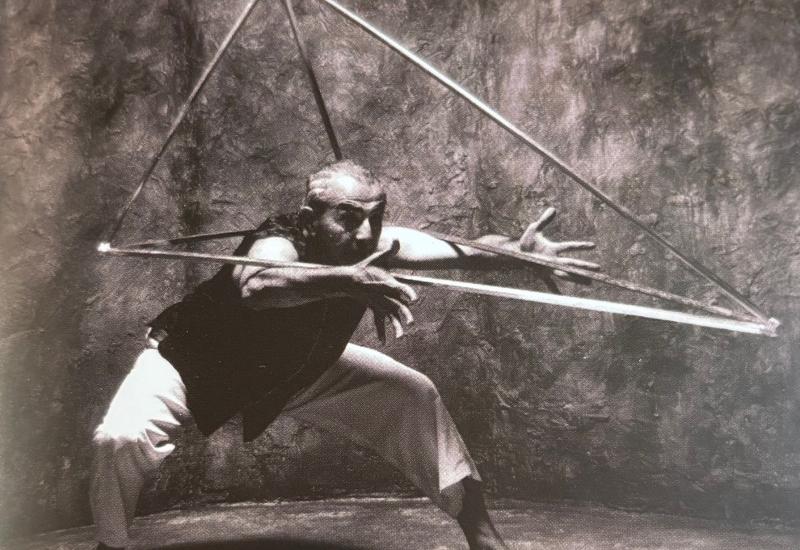

Aruna Sairam’s return to the Darbar Festival was a late morning into early afternoon recital. She last appeared at Darbar in September 2016. Every Aruna Sairam concert comes with the likelihood of being taken on a grand adventure. This concert did just that. Of all her extensive discography the audio-recordings to which I return most often are the ones Charsur Digital Work Station preserved between 2001 and 2006. The Chennai-based label recorded her at various venues on her and the company’s home-turf during the Margazhi (December/January) season. Maybe romantically, this concert felt to these ears like closest London has ever witnessed to those performances. What no audio-recording can ever capture is the electrifying visuality of her live performance. The physicality of her performance, the eye contact, the unspoken make Aruna Sairam is a must-see.

The storyteller Hugh Lupton recalled the magnificent Scottish Traveller storyteller, Duncan Williamson telling him, “When you tell a story or sing a song the person you heard it from is standing behind you. When that person spoke he, in turn, had a teller behind him, and so on, back and back and back. […] [T]he story has to speak to its own time, but the teller has also to be true to the chain of voices that inform him or her.”

Aruna Sairam is a kathakar – Sanskrit for ‘storyteller’. Assisting her in this Carnatic story-telling adventure were the melodist Jyotsna Srikanth on violin, the rhythmists Sai Giridhar on mridangam (double-headed barrel drum) and Giridhar Udupa on ghatam (tuned clay pot), and two tanpura players tracking the tonic behind her. And they were good.

The first name in the chain she called upon was Mysore Vasudevachar (1865–1961). She chose a kriti – from the Sanskrit, literally, ‘creation’ or ‘work’. They are conventional opening gambits. It sounds glib to call them a star in the compositional crown of Carnatic song, yet that is what they are. She sang his ‘Mamavatu Shri Saraswati’, composed in Sanskrit and set in Ragam Hindolam. Taking about a quarter of an hour to unfold, her first tale-in-melody was a dive into the deep end. Next, after the namaskar and good morning pleasantries, she and the ensemble went straight in and dived deeper with Tyagaraja (1767–1847). He is one of the trinity of Hindu saint-composers whose combined inspiration underpins, deep breath, most everything in Carnatic music. She chose the fifth of his pancharatnas (‘five gems’), ‘Endaro Mahanubhavulu’, composed in Telugu and set in rāgam Sri.

Building, building, the recital approached high noon and its fireworks display: a Ragam Tanam Pallavi in Keeravani in fives and fours. The RTP is the three-stage showcase. It allows musicians to improvise far more than most Carnatic expositions, which stick close to the composition’s ‘script’. It evolved into a ragamalika or ‘garland of ragas’. It explored Behag and Ranjani in sargam. Sargam sings a composition’s notes rather than its words. She poured out the non-lexical with an intensity and agility to match Ella Fitzgerald scat singing in full flight. It included a series of vocal and violin call-and-response sections before landing back in Keeravani. To conclude there was a splendid percussion exchange. Aruna Sairam switched to finger computing, rather than counting matra or beats.

With time running out, Aruna Sairam introduced the Tamil folksong ‘Maadu Meikum Kanne’. She introduced it as a conversation between Lord Krishna and his mother, Yashoda. She tries to dissuade him from going into the forest and lists its dangers such as thieves and wild animals. Entering into the spirit of the narrative, Jyotsna Srikanth slipped in a plucked violin passage. Sairam acted out parts, at one point shielding each eye to look in turn. In danger of overrunning, she dived into the magnificent tillana, ‘Kalinga Nartana’ in ragam Gambhira Nattai. Tillana is a rhythmic form, also found in dance. She had no time to explain this tale by the prolific composer Ootukkadu Venkatasubba Iyer (c. 1700–1765). It tells the tale of Krishna subduing the multi-headed naga Kalinga or Kaliya. He defeats the poisonous serpent being by dancing on its heads. Most of the audience seemed to know the story anyway. Talking after the recital, she said ‘Kalinga Nartana’ had become a “signature song”.

Such a spirited flourish typically ends a concert. Although time had run out, the Darbar Festival’s Artistic Director, Sandeep Virdee requested another item. She sang composer Adi Shankaracharya’s ‘Shabda Brahma Mayi’, a shloka in Sanskrit in Devi Meenakshi. It segued into an Italian Marion lauda, a Christian liturgical song form, with light violin accompaniment. It was “an Ode to Divine Mother Mary” learned from her collaborator, Dominique Vellard, the Basel-based, French singer whose work focuses on medieval and Renaissance music. It ended the recital in an unexpected way.

Towards the end of the last century, when physical reference works reigned paramount, I wrote for Michael Erlewine’s All Music Guide. One entry was for the then-living, Carnatic vocalist, M. S. Subbulakshmi (1916–2004). Jawaharlal Nehru hailed the “Queen of Music”. My entry ended: “In India her status is unassailable and any future contender for her crown will have to be special indeed.” After decades of listening to her recorded work and seeing her perform live, Aruna Sairam has proved herself worthy of wearing the crown. Aruna Sairam is a storyteller in the business of transporting minds.