The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence

Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Until 5 May 2025

Reviewed by Charles Robertson

The exhibition draws together material from the V & A’s own very rich collection with important loans from a range of private and overseas collections. It offers an absorbing exploration of a fascinating period of cultural history. This is more than simple enchantment or interest because the style is not just evidently beautiful but one of the most successful creations in all human culture. Mughal art and culture present a conundrum. On one hand it is quintessentially a court style articulating the life and power of a small elite; on the other it is highly eclectic, comprehending multiple elements, from India, Central Asia, Persia and as it developed, absorbing powerful influences from Europe. The style ultimately goes on to signify India, which no amount of Hindu nationalism will efface from the public mind. This is clear in a million paisley patterns, the onion profile of the Taj Mahal, the obsequious bow of the Air India Maharajah, a figure inspired by miniature painting. If India is a brand then the Mughal episode is crucial in its consolidation.

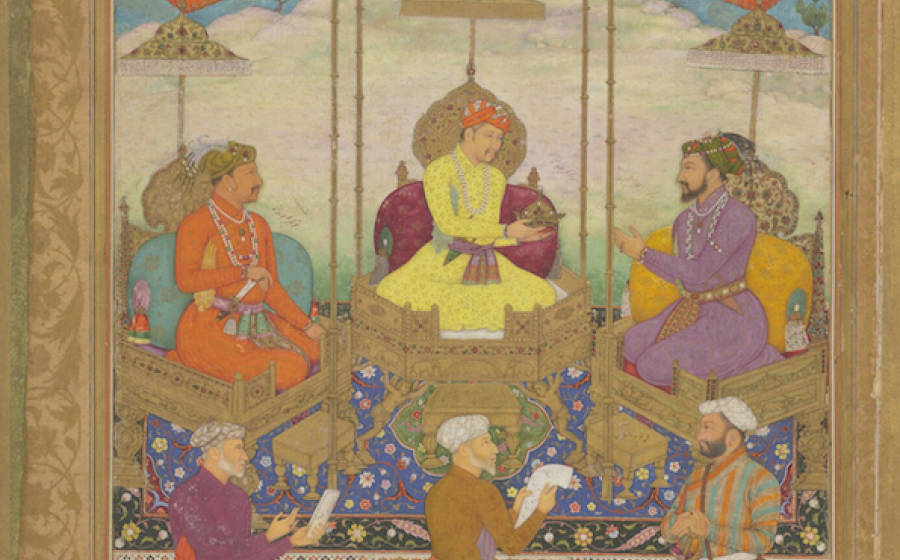

This exhibition concentrates on the applied arts and miniature painting in a core period of three emperors, from the accession of Akbar in 1556 to the fall of Shah Jahan just over a century later. Its great strength is to show the whole culture from its representation in miniatures to its expression in a remarkable range of applied arts from jewellery to arms, metalwork and armour. At one level this is very refined and internalised, produced for a restricted elite audience; at another, expansive, as a whole range of manufacturing and skill over northern and central India were drawn upon to ornament the court and project the image of the ruler. There are wonderful examples of carved jade and jewellery and glorious textiles. A novelty in the exhibition is the inclusion of considerable amounts of metalwork. It was very impressive to see the actual objects which are represented in the miniatures.

The culture comes alive in the painted miniatures. These include vivid representations of court ceremonies and contemporary events, multiple portraits of emperors and their courtiers and a vast range of subjects including exotic animals. There are extraordinary illustrated narratives, notably the Hamzanama created for Akbar. Their form of painting started with Persian models but then included much from native Indian traditions. From the beginning of the 17th Century there was considerable impact of European engravings which were enthusiastically consumed and adapted. The compliment was to be returned by Rembrandt who made copies of an album of Mughal court portraits to refine his representation of the east.

We can’t fully understand Mughal achievement without its architecture. Mughal architecture articulates competing elements from the previous Sultanate and Persian models; and although it is included in the exhibition title, architecture is dealt with almost tangentially. Buildings and spaces also provide the context in which the objects displayed were used and where court life took place. For example, photographs of the Red Fort could have shown the avenue of shops forming a bazaar and private apartments provided with niches for the display of objects. The court ceremony is actualised by both the public and private Diwan, audience halls. It can be difficult in an object-based exhibition to include photographs; however the Shah Abbas exhibition at the British Museum some years ago included a very compelling projection of images of buildings.

The Victoria & Albert Museum has particularly rich collections but there is a deeper story. The visitor will note that though all the objects were made in India they are now in foreign collections. Most simply the British Empire ultimately replaced what had been the Mughul one. In the 1790s George the third had already been presented with the Padshahnama, a record of events in the life of Shah Jahan and one of the most spectacular Mughal manuscripts. In fact in India the supremely elegant drawings of the tombs in the Taj Mahal are from Company School miniatures specifically made for Europeans in India after 1800. In the early 19th Century the fascination with Mughal culture gave rise to the magical Royal Pavilion at Brighton, clothed in random but enthusiastic reference to Indian mosques and palaces. Rather like their Mughlai food the result is rich, refined, delicious but sometimes a bit excessive.