Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company

Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company

Wallace Collection, London

Until Sunday 29 April 2020

This is the first exhibition in Britain entirely devoted to the wide range of paintings made by Indian artists for British patrons in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Curated by William Dalrymple with a group of leading scholars, the exhibition is a very rich, and in some ways troubling, experience.

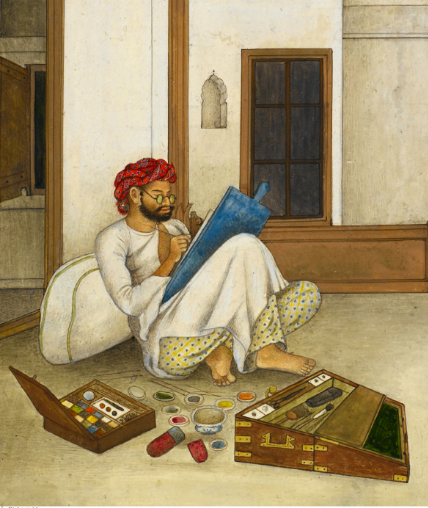

These used to be called ‘Company School Paintings’, a reductive term which the authors of the catalogue are rightly keen to reject. While the circumstances of production were indeed created by the British, the genius was very much Indian. Moreover, there is not one style or school as the works were produced in a number of places over the subcontinent, including Calcutta, Patna, Delhi and Madras, and represent multiple things, from natural history to topography and ethnography. The painters came from different backgrounds as court artists but also perhaps from the Kalamkari tradition of fabric decoration. The function is purposely representational and as the catalogue points out, ultimately to be replaced by photography. Though often exquisite, not always beautiful, they are generally compelling.

![Family of Ghulam Ali Khan, Six Recruits, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M Sackler Gallery [Smithsonian Institution]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Family%20of%20Ghulam%20Ali%20Khan%2C%20Six%20Recruits%2C%20Freer%20Gallery%20of%20Art%20and%20Arthur%20M%20Sackler%20Gallery%20%5BSmithsonian%20Institution%5D.jpg)

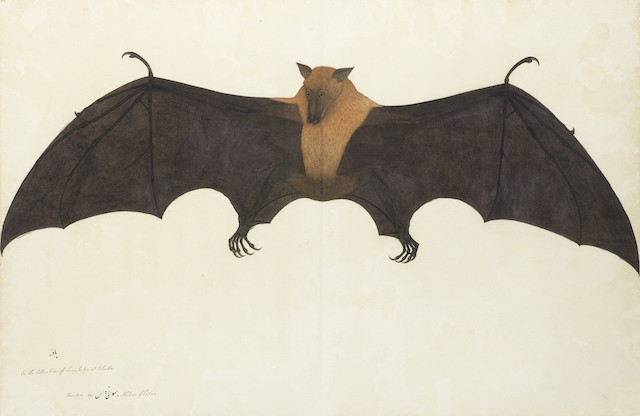

A starting point is the realisation that though these are works on paper, they are paintings. Although the artists use high quality imported Whatman paper and sometimes new watercolour paints, the notion of painting was firmly within the tradition of Indian art, where works on paper are predominantly paintings, not drawings, as they would be in Europe. The natural history images, particularly the animals, are extraordinary: the technique eschews outline and the delicate brush work replicates the effects of fur or feather, making for vividly direct impact

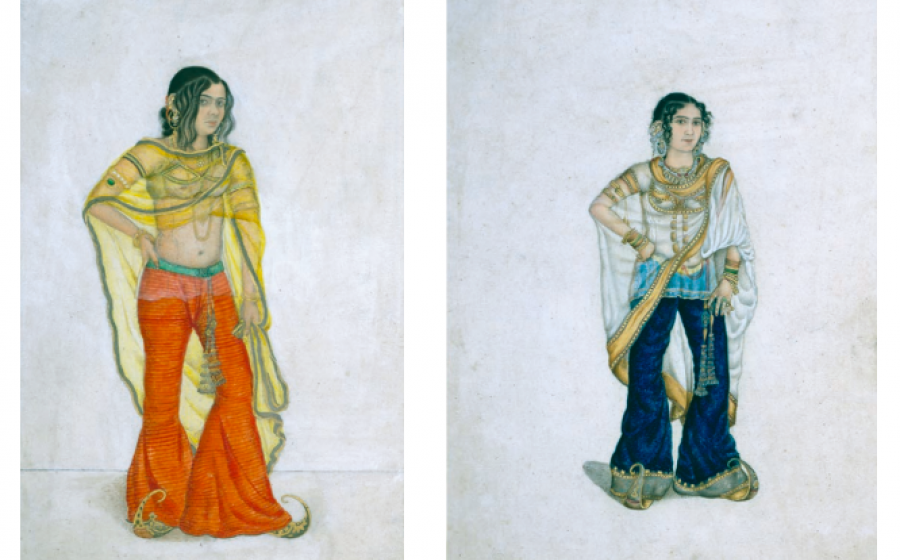

While they are produced in an imperial context they are made by the dominated culture for their foreign masters; so there is a quality of auto description; and the encounter, insofar as there is one, could be pretty raw. Among the most interesting, and perhaps troubling, drawings, are those for the so-called Fraser and Skinner albums produced in Delhi. They include army-recruits, soldiers, traders and villagers. The incisive angular figures, eyeing the viewer balefully, emerge from white paper, reminding one almost of Egon Schiele. There is also the extraordinary series of images of nautch girls employed by James Skinner, a soldier of fortune born to a Scots father and an Indian mother, showing a remarkable actuality both of bodies and dress for dancing.

The exhibition concludes with the large mostly landscape drawings by Sita Ram associated with Governor General, Lord Hastings. A strong case is made for Sita Ram as a very original artist. He is, however, an instance of an artist who engaged with European art in its own terms – he was highly influenced by its conventions. In some ways art has lost its power and the searing power of self presentation was undermined by an appropriated notion of the picturesque.

Taken together, the importance of these painters is that they mark Indian responses to modernity, prompted in part by the encounter with the British, as much as by an intellectual figure such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy. We need to value the moment before Indian visual culture was subverted by the prevailing orientalism ultimately favoured by the British and still evident in Indian Government Craft Emporia.